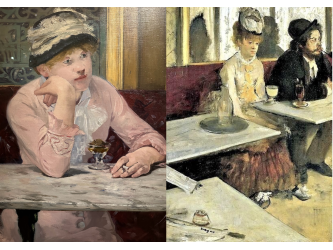

An Irishman and an American dandy

Take an American dandy who liked women, wild animals and photography. Then take another dandy, an Irishman who loved men and made paintings depicting torment and suffering with elaborate and dramatic mastery. (See here and here reports about Francis Bacon). The unexpected dialogue between these two figures is being displayed in London by the gallerist Pilar Ordovas.

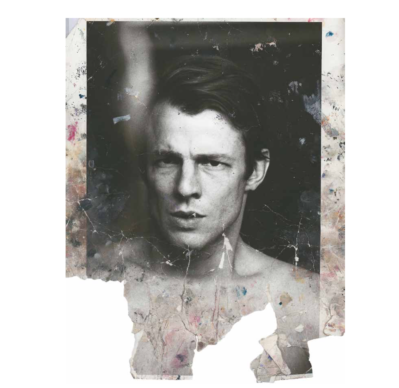

P Beard in F Bacon’s studio

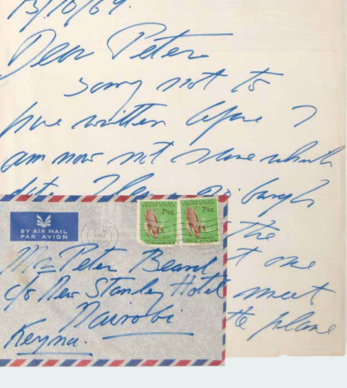

Extensive correspondance

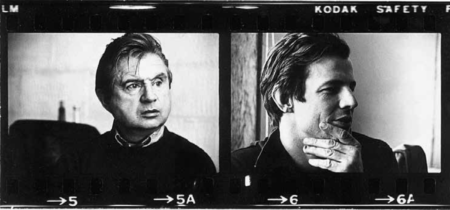

It’s the story of how the superstar of contemporary painting Francis Bacon (1908-1992) and the legendary adventurer and photographer Peter Beard (1938-2020) met one another, liked one another, and nurtured a strong bond, which was also bolstered through their extensive correspondence. Because contrary to what one might think, the Irish painter and American photographer had various things in common.

Bones form magnificent sculptures

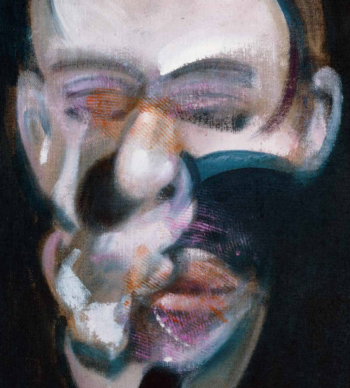

“Over the years, Peter Beard has given me many of his beautiful photographs. For me, the most poignant are the ones of decomposing elephants where, over time, as they disintegrate, the bones form magnificent sculptures, which are not just abstract forms, but have all the memory traces of life’s futility and despair,” recounted Francis Bacon. The pair first met in 1967 and, according to Pilar Ordovas, Bacon painted nine works inspired by his photographs and at least eight portraits that use his features.

F Bacon to P Beard

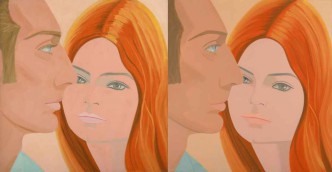

Beard was a muse

“Beard was a kind of muse, an inspiration for Bacon.” At the London gallery we can see “Two Studies for Portrait” from 1976 in which we recognize the features of the American gentleman. Yet their shared source of fascination lay further afield than London and New York.

Apocalyptic anxiety

It was thanks to a love of the wilds of Africa that they found one another. In Beard’s case, he first travelled to Kenya at the age of 17. This experience went on to literally transform his life. He went to Zululand in the company of the explorer Quentin Keynes, great-grandson of Charles Darwin, before going on to live there periodically. He literally embraced life in the wilderness there with what it contained of “apocalyptic anxiety”, as we can rightly read in the exhibition catalogue. From very early on, his creative output assumed an original format, that of a diary in which images and composites were accompanied by writings. 1964-1965: his time stops on the continent.

He worked at Tsavo national park in Kenya. His aim was to denounce the destruction of an area of land usually occupied by elephants. That was how he documented the tragic deaths of 35,000 of the animals. He went on to publish a landmark book on the subject: “The End of the Game”.

Animal kingdom

Peter Beard

In the case of Bacon, we observe an Irishman who was a decorator for a short time, caught in a spiral of self-destructive torment, who created atmospheric works with jarring colours depicting the dramas of life and the beauty of a certain kind of suffering. He visited South Africa in 1951 to see his mother and sisters. While there, he was also struck by the power of the animal kingdom.

1967

P Beard’s diaries

It was in 1967, when the photographer had just been the subject of an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, that he decided to distance himself once more from the American glitz and glamour and travelled to Kenya, making a stopover in London. Good thing he did, since at the opening of an exhibition of Francis Bacon’s work at the Marlborough gallery, the two men met. Their first meeting was followed by a lunch. The painter was far from unaware of the adventurer’s physical beauty. He would become one of his sources of inspiration.

In Dublin, the city gallery, the Hugh Lane, has bought and reconstructed the entire universe of Francis Bacon’s little London studio, centimetre by centimetre. It has 7000 pieces arranged in a spirit of utter chaos which particularly showcase the mounds of images – including photos of Peter Beard – which served as the basis for Bacon’s visual flair. They both had a taste for iconographic profusion, for fragments, and the theatricalization of life.

https://youtu.be/DpvffyFouXY

Ode to Bacon

From P Beard to F Bacon;

The exhibition features a black and white image composed of a deserted beach where the sand is marked by the tracks of a passing animal. They lead to a deformed mass of bones or pieces of wood. The photographer gave it the enigmatic title: “Man without a dog, Ode to Bacon”. It is framed by an outline of blood smeared on by hand. Beard, like his Irish friend, aestheticized drama.

Time and photography

From P Beard to F Bacon;

In one of his letters to the older painter, he confessed that their discussions had encouraged him to think about the role that time plays in photography. Beard recorded his life in words and snapshots, assembled like a chaotic puzzle in his African diary. Various notebooks from his youth were burned in the 1970s in a fire at his American home in Montauk. This little town in Long Island, known for its lighthouse, was nicknamed “The end of the world”. It was also here, at the end of the world, where Peter Beard died in April 2020.

www.ordovasart.com. ( until 16 july)

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.