In ancient times, for example, the centre of the world for Westerners was Athens followed by Rome, each of which was proud of its status as the central seat of power, whereas elsewhere, in the Andes Mountains, among others, an entirely different “centre of the world” existed.

We used to think our sun was unique in the universe. But there were many others.

Nowadays it’s more complicated, since the media who inundate us with supposedly exhaustive information seek out the spectacular all over the planet.

From an artistic standpoint, should we say that New York is the Centre of the World?

It is without doubt the centre of the global art market, but excluding that nothing could be less certain.

An illuminating exhibition on show at the Guggenheim New York places the vast and varied territory of China at the centre of the art world until 7 January 2018, before the exhibition is due to move to the global centre for cutting-edge technology, San Francisco (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, from 20 November 2018 until 24 February 2019).

And if there’s any country that seeks to be at the centre, it’s surely the nation that long referred to itself as the Middle Kingdom.

The Guggenheim exhibition, which occupies the whole of the building’s central spiral, is conceived in six parts, but in the style of a large market in which all genres, all concepts and all sizes are exhibited at once.

It brings together 71 artists. The ground it covers is vast and the sheer number of offerings is even greater.

The exhibition focuses on the period from 1989 (the Tiananmen protests and economic reforms) up to the Olympic Games held in China in 2008.

The country transforms into a colossal economic power and the artists bear witness to and act out this new image.

Hou Hanru, the director of the MAXXI in Rome who has witnessed these metamorphoses, is one of the exhibition’s two guest curators.

He talks about what he wanted to show at the Guggenheim:

But as fate would have it the artwork that lends part of its title to the exhibition, “Theater of the World” – a monumental piece conceived by a very brilliant artist who lives in Paris, Huang Yong Ping – was banned before the exhibition had even opened.

The first time was in 1992, when he erected a gigantic cage in the form of a corridor and placed within it various reptiles and insects which were left to fight mercilessly for their individual survival.

The artist envisaged, we imagine, an allegory of globalization; the worldwide battle for economic interests which leaves entire swathes of populations and territories in the dust.

Hou Hanru talks about the campaign – which was successful – to ban the piece, waged by animal protection organizations, and how Huang Yong Ping reacted.

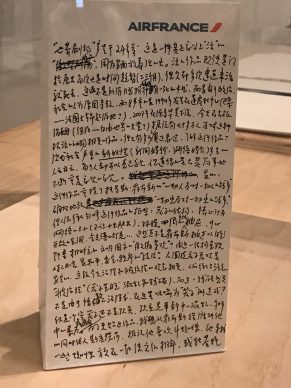

On the plane travelling to the preview of the show in New York, the artist wrote a statement on a paper bag designed to collect the vomit of airsickness victims, commenting on what had happened and explaining that the whole business of the ban itself pretty well summed up the nature of human conflict.

The paper bag is on display at the Guggenheim alongside the empty cage.

Philip Tinari, a well-known Sinophile and director of the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing, is the other guest curator of the exhibition. He in turn outlines what he has tried to do through this exhibition.

In China there exists a multiplicity of styles, modes of expression, and desires for an artistic existence, and it is this kind of chaos of creative offerings that the New York exhibition conveys perfectly.

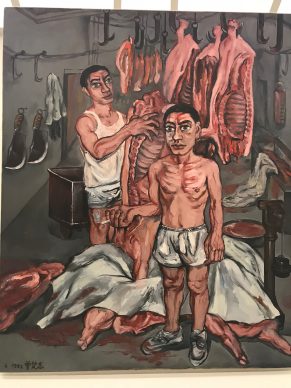

Zeng Fanzhi created “Meat” in 1992, a series of paintings made in a very powerful expressionistic style, which describe how on midsummer days in his town the coolest place to be was around the butchers’ shops, where people would stretch themselves out on the frozen meat for a siesta.

The human carcass merges with that of the animal.

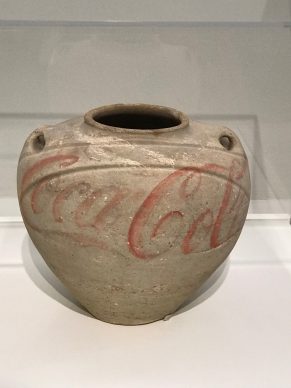

Of course, the most famous Chinese artist in the world right now is Ai Weiwei, and this exhibition presents several pieces of his, including one of his Han dynasty vases on which he has printed “Coca Cola” in Chinese, to signal the contemporary intermingling of cultural identities.

The artist Chen Zhen (1955-2000), like Huang Yong Ping, also lived in Paris after leaving China, and like him his work acts a bridge between Chinese and Western cultures.

In 2007 Cao Fei conceived an extraordinary video resembling a game, featuring an uninhabitable virtual city of skyscrapers that is chaotic, filled with precipices, and driven by money, called “RMB City”.

Cai Guo-Qiang, who had the honour of exhibiting in the whole New York Guggenheim in 2010, plays with the tradition of fireworks to create shapes and signs on paper.

Yang Fudong (born in 1971) creates sublime films which seem to draw on the French Nouvelle Vague of the 1960s to describe the Chinese youth and their awakening to and love of both avid knowledge and avid consumerism.

In 2016 the Vuitton foundation in Paris had already dedicated an intelligent exhibition in Paris to the Chinese contemporary art scene, featuring many of the artists exhibited today at the Guggenheim.

It’s about time that contemporary art from the former Middle Kingdom was examined in a setting beyond that of the auction catalogues.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.