660 km from Paris, deep in the heart of Aveyron in the South of France, there’s a town that cannot be accessed by motorway or by the TGV – neither of them travel through here – where you can visit the most substantial exhibition in the world right now dedicated to a major Japanese avant-garde movement that emerged in the mid-1950s and disappeared in 1972: Gutai.

The show is made up of forty-odd artworks and 19 artists displayed in the beautiful corten steel-clad museum that opened in 2014 in the native town of abstract painter Pierre Soulages and is named after him.

Gutai emerged from the tabula rasa left by the American nuclear strikes on Japan.

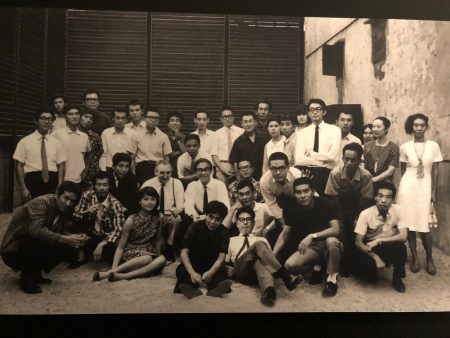

Far from the country’s capital, in the province of Kansai, a group of young people wanted to create a completely new and iconoclastic kind of art that in no way adhered to the weighty traditions of Japan nor those of Western art, even though they were familiar with surrealism and Dadaism.

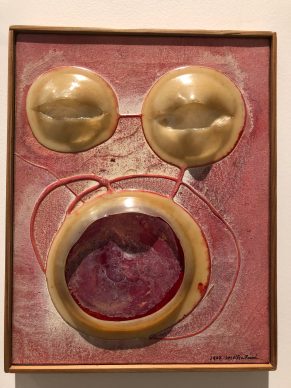

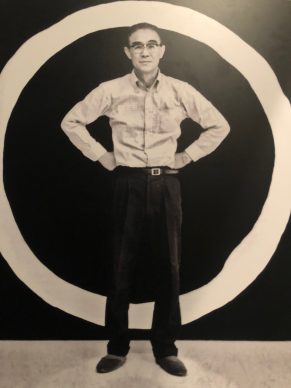

Jiro Yoshihara (1905-1972), the founder of the movement (which also died with him), surrounded himself with avid disciples. “We’d lost everything, but our mentality was fresh,” emphasizes Takesada Matsutani (born in 1937), the youngest member of the movement, who has lived in Paris for 29 years and is featured in the exhibition, among others, with an artwork made from a mishmash of paint, glue and sexual desire.

The artist, who joined the Hauser & Wirth gallery roster, explains the genesis of his artwork dating from 1964:

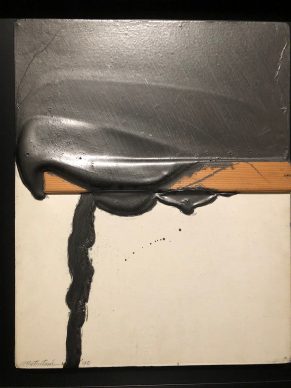

In his manifesto Jiro explains: “Gutai art does not transform, it does not falsify matter, Gutai art gives matter life.”

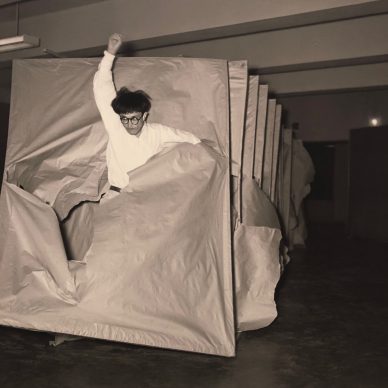

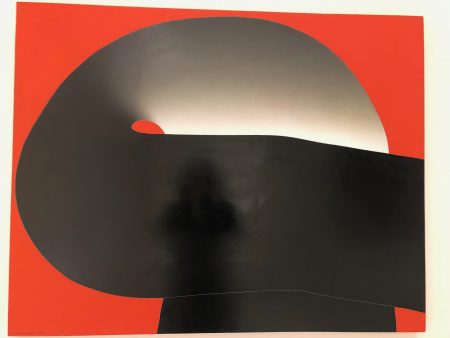

The artworks must appeal to all senses, to the whole body, and be veritable sensory explosions.

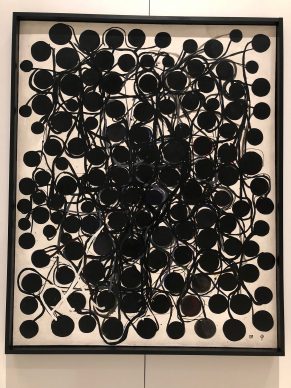

It is with this aim that the female artist Atsuko Tanaka (1932-2005) plays using electric bells.

She creates a chain of sounds (which can be seen in the exhibition) and transcribes these sonorous pathways on canvas using black or coloured circles that link together.

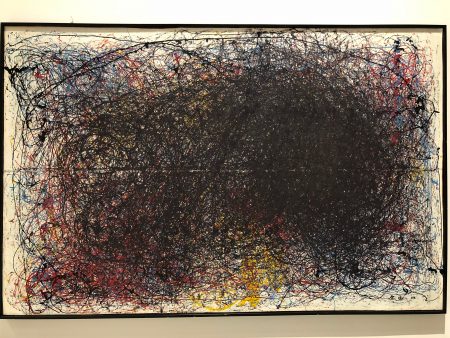

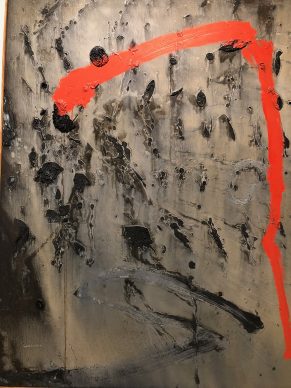

Shozo Shimamoto (1928-2013) creates his compositions by throwing glass bottles filled with paint that explode upon impact.

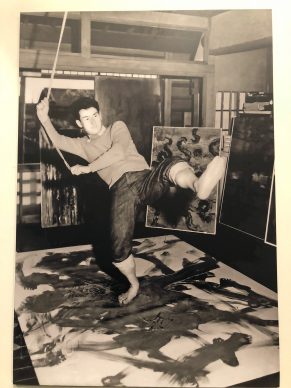

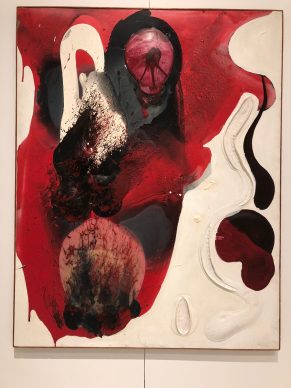

The most impressive of these artists is Kazuo Shiraga (1924-2008), who swung from a rope attached to the ceiling to paint the canvas with his feet in a sheer frenzy, creating works of pure pictorial chaos. The paint itself is all matter, often in shades of blood red. Like raw flesh.

In Gutai art, matter is allied with the Japanese “spirit-breath”, the Ki, the life force that inspires action.

All these initial “actions take place far from the studio, from which one must also liberate oneself.” The first large-scale Gutai exhibition took place in the open air in a park and finished the day before the commemoration of the catastrophe at Hiroshima, known as the “day of peace” in Japan.

The researcher and specialist on the country, Michael Lucken, explains that it was with the arrival of the French art critic Michel Tapié (1909-1987), who later brought the movement to international renown, that Gutai began to take on a more commercial quality, limiting itself more willingly to works on canvas.

We might reproach the Rodez exhibition for conveying little of the living, restless aspect to the Gutai movement, unless you count a few photos displayed too far away from the artworks.

However, we welcome the inclusion of 16 works from the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art in Kobe, which has the largest Gutai collection in the world.

Yutaka Mino, the director of the museum, says that it wasn’t until well after the 1980s that the Japanese themselves started to take an interest in the movement, which they considered to be that of madmen.

How do you say it in Japanese? “No man is a prophet in his own land.”

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.