Since the purpose of this blog is to communicate my artistic impressions, it may seem strange to maintain total silence on an artistic project with which I have been intensely preoccupied for the past two years, and since I am obviously not going to review the exhibition, I have decided to reproduce here a very short extract from the introduction to the bilingual (French, English) catalogue forthcoming in July.

“How the West got China wrong”. It was 7 March 2018. On Instagram, the studio of the famous Danish artist Olafur Eliasson (242,000 followers) posted an image of Eliasson posing alongside the famous Chinese artist Ai Weiwei (402,000 followers) holding a copy of The Economist with this headline emblazoned across its cover. Both artists appeared to be laughing.

This image tells many stories.

( …)

But without doubt the most important story touches on issues that extend beyond the artistic dimension.

The West, in the past as in the present and despite all its current efforts to show openness towards this giant turned leviathan of global wealth, still fails to understand China. While The Economist’s headline alludes to the assumption of power for life of the president of the former Middle Kingdom, Xi Jinping, it so happens that this inability to understand one another has long caused a rift between these two parts of the world. Their modes of thought, writing, perceiving reality, destroying the past, and worship, are often quite different.

One of the values of Ai Weiwei’s work, therefore, is not only the ability to travel through time but also through space. He brings China to the West. And we can no longer afford to ignore or allow ourselves to misunderstand this country. Ai Weiwei’s work bears many similarities to Chinese writing, as described by the prescient French sinologist Marcel Granet (1884-1940) in his book La Pensée chinoise (“Chinese Thought”). He claims that Chinese writing has the merit of being practical rather than intellectual: “Independent of local pronunciation, its principal advantage lies in being what we might call a writing of civilization.” Ai practises an art of civilizations.

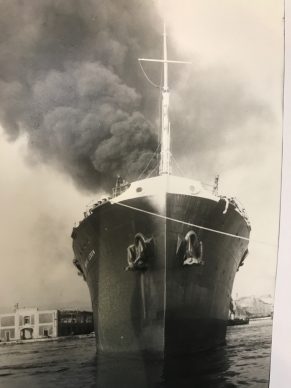

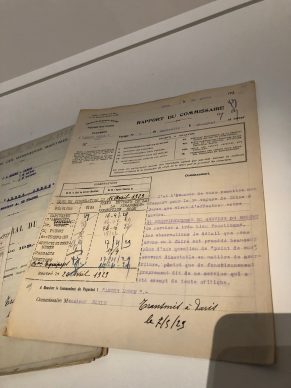

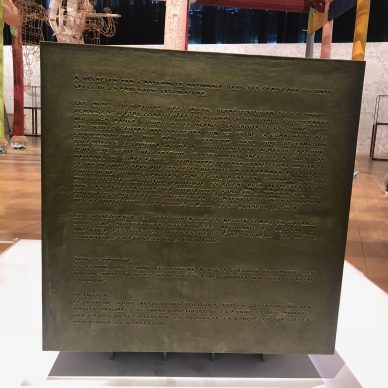

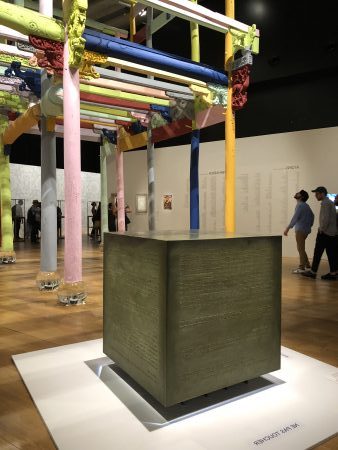

Granet goes on to say that, “the complex characters should be understood in terms of a rebus”. Certain works by Ai Weiwei also follow the rebus principle, much like the title of his exhibition in Marseille: Fan-Tan. This refers to the nickname given by Chinese labourers to a tank offered by one of their wealthy compatriots to the Allies during the First World War. This tank had an eye painted on its side, the same eye that can be found today on the Marseille soap works created by Ai Weiwei. Fan-Tan is also the name of a Chinese game, similar to casino roulette. For the artist, it is a way of conveying how the history of Franco-Chinese relations has its own elements of chance and chaos.

In fact, through reading Granet we understand that Ai Weiwei is also a storyteller, only his stories take three-dimensional form. As the sinologist observes: “When they want to prove or to explain, when they wish to recount or to describe, the most original authors make use of stereotypical anecdotes and set expressions, drawn from a common background.”

(…)

In 1933, the writer Paul Valéry – who was incidentally one of the inspirations for the theorist of surrealism, André Breton – was asked to write an introduction for an exhibition at the Jeu de Paume of Chinese painters from the diaspora. His words might well serve as a conclusion for an exhibition in 2018: “We are living through the trial and error of a new age, in whose arrangement all men, all races, all forms of culture will be necessarily engaged and implicated ever more intimately, the likes of which have never been seen before.”

Marcel Granet, La Pensée chinoise, Paris, Albin Michel, 1999.

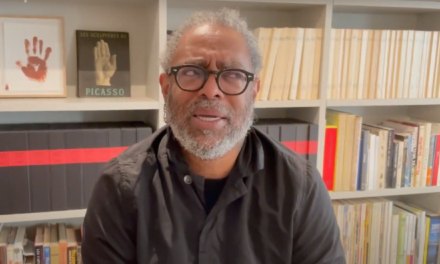

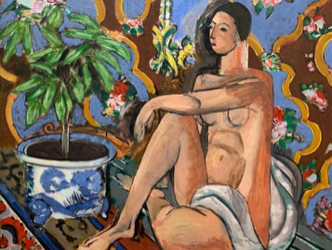

This report includes photos from the exhibition and photos that I took during Ai Weiwei’s visit to Marseille last July

Ai Weiwei: Fan-Tan

Until 12 november. Mucem. Marseille.

www.mucem.org/en/ai-weiwei-fan-tan

Mucem exhibition catalogue, French-English bilingual edition, edited by Judith Benhamou-Huet

Featuring interviews with Ai Weiwei, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Uli Sigg, plus new translations of Ai Qing’s poetry and contributions from Patrick Boulanger, Emilie Girard and Emmanuel Lincot.

Marseille, co-published by Mucem / Manuella Editions

ISBN: 978-2-917217-99-3

Available July 2018

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.