No taboos

Super-erotic and without taboos. Nicolas Poussin(1594-1665), an artist’s artist favoured by art historians, considered to be the most austere of his era, had a period that was decidedly risqué. The painter who was the subject of a 2015 exhibition at the Louvre on his relationship with god, for example, who wanted to leave behind the legacy of a scholar, as in his self-portrait which hangs today in the Louvre, also produced highly sexual compositions.

Great beauty

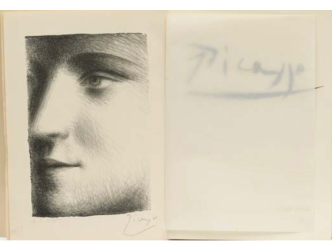

Until 5 March at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon there is an exceptional exhibition on this theme, entitled “Poussin et l’amour”. The forty-odd paintings and drawings assembled are first and foremost a major lesson in art history and an example of great beauty. We see a Poussin inspired by the flair of Titian (see the Venus of Urbino from Florence of the Danaë from Madrid). We also sense the legacy he left to the likes of Courbet, Ingres, Picabia or more recently John Currin. The Musée des Beaux-Arts also zooms in on the way in which Picasso took inspiration from Poussin’s Bacchanales. It’s worth recalling that Jeff Koons also collects paintings by the French artist.

Voyeuristically

When the young Nicolas was preparing to leave for Italy, during his early years in Rome between 1624 and 1630, he churned out pictures of voluptuous, languid naked women, in the throes of ecstasy or about to be, surrounded by lustful gentlemen, showing pleasure, affection, amorously and voyeuristically. No trace of guilt. No sinful serpent waiting behind a tree… But why has this side of the painter been hidden for so many centuries?

Pierre Rosenberg

According to Pierre Rosenberg, the charismatic art historian and former head of the Louvre who has been working on the artist’s catalogue raisonné (1) for 50 years, “for a long time the historians who specialized in the subject wanted to preserve the image of the serious painter which was also associated with Poussin. Perhaps the fact that they were all homosexuals, during a conservative period, made them less inclined to reveal the more scandalous side to Poussin. This facet of him was disturbing. They also had trouble accepting depictions of men and women masturbating. So Venus and the satyrs remained for a long time in the basements of the National Gallery, and there was even doubt over its attribution to Poussin.”

Origine du monde

Here we see the beautiful female figure placing her hand over her “Origine du monde” (after Courbet’s painting) which according to specialists implies she is about to pleasure herself. Also according to them, the satyr hidden behind the tree seems to be engaged in the same activity.

Famous Libertine

Michael Szanto, co-curator of the Lyon exhibition, reveals that this obsession in the painter’s work had its origins, not in an encounter with a women, but rather with an Italian poet, Giambattista Marino (1569-1625). This famous libertine, a protégé at the French court of Marie de Médicis, inspired the young artist, who depicted him, among others, in “L’inspiration du poète”. “Giambattista Marino argued that creation took place under the strongest of passions. And the most powerful of these is love,” analyses Michael Szanto.

Symbols

Even if the paintings exhibited in Lyon seem from one angle to be less complex than usual in Poussin’s work, he still plays with symbols. Of course there are the angels, which proliferate in these compositions, who let fly their arrows of love. Dogs represent fidelity, the swan is one of Venus’s attributes, and the pair of doves is shared sentiments. In “Le triomphe d’Ovide” made around 1624 he expressed his admiration for a contemporary Ovid, his friend Marino.

The stream of milk

In the foreground a dozing Venus watches her breast being squeezed by a cherub while another dips his arrow into the stream of milk. The sumptuous “Nymphe épiée par deux bergers” presents herself, sleeping, with her arms above her head, her crotch outlined with a gossamer veil. Even more daringly, painted around 1625 “Mars et Vénus” depicts a goddess bold enough to make the sign of the horns at her cuckolded lover, while Adonis bides his time in the distance.

In the foreground a dozing Venus watches her breast being squeezed by a cherub while another dips his arrow into the stream of milk. The sumptuous “Nymphe épiée par deux bergers” presents herself, sleeping, with her arms above her head, her crotch outlined with a gossamer veil. Even more daringly, painted around 1625 “Mars et Vénus” depicts a goddess bold enough to make the sign of the horns at her cuckolded lover, while Adonis bides his time in the distance.

Arte e una cosa mentale

No personal explanations have been found that can truly justify the sexual obsession in this period of Poussin’s work. No fleeting romances or sensual relationships emerge from his correspondence, apart from the fact that – according to Pierre Rosenberg – he contracted syphilis at a very young age and his marriage failed to produce a child. So why? As Leonardo said, “arte e una cosa mentale”. Pierre Rosenberg concluded in other terms: “Moses or Venus, it’s always himself. Even sex is intellectual in the work of Poussin.” (1) Nicolas Poussin. Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint. 4 volumes. Flammarion publication at the end of 2023.

No personal explanations have been found that can truly justify the sexual obsession in this period of Poussin’s work. No fleeting romances or sensual relationships emerge from his correspondence, apart from the fact that – according to Pierre Rosenberg – he contracted syphilis at a very young age and his marriage failed to produce a child. So why? As Leonardo said, “arte e una cosa mentale”. Pierre Rosenberg concluded in other terms: “Moses or Venus, it’s always himself. Even sex is intellectual in the work of Poussin.” (1) Nicolas Poussin. Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint. 4 volumes. Flammarion publication at the end of 2023.

Poussin et l’amour. Until 5 March. www.mba-lyon.fr

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.