The danger when one possesses many artworks lies in wanting to display them all, in seeking to make a show of strength.

In contemporary art, taking into account the diversity of forms and the scale of the artworks, ultimately the supreme luxury is time and space.

One of the archetypal sites of success in this regard is the Dia Beacon (1) in the United States.

In Europe, in another regard entirely, there is an institution that has demonstrated that it has ample time and space ever since its opening in 2015: the Prada foundation in Milan.

Here, it is fashion designer Miuccia Prada and her husband who is in charge of the business, Patrizio Bertelli, who oversee a space in a former distillery (19 000 m2) which is a mirror of their universe: eclectic, curious, intelligent and above all, elegant.

The attention to detail here is impressive.

The café is not just a place to relax but also a fantasy space, a kind of time capsule designed by the American film director Wes Anderson. Bar Luce is decorated in candy colours with little individual tables, a throw-back to an elegant 1950s Milan that has never got old.

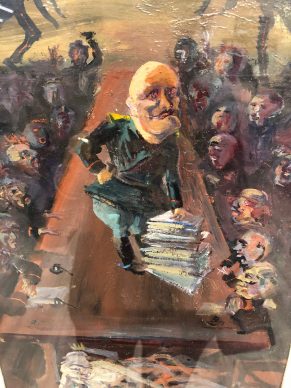

The space and the intelligence are due to a plethoric exhibition until 25 June dedicated to the politics and art of Italy between the years of 1918 and 1943 including of course, all the neoclassical, fascist art from the Mussolini period.

It comprises no less than 600 works re-contextualized by the foundation’s favourite curator, Germano Celant.

Germano Celant talks about a “village of ideas” for the Prada foundation:

But if we’re talking about elegance and time then we should above all mention the new tower designed, like the rest of the renovated foundation, by Rem Koolhaas, specifically to house the permanent collection.

It stands 60 metres tall with 2000 m2 of exhibition space across six floors of the building, which has nine floors in total.

The Dutch architect relishes an intellectual challenge, so he chose to adapt each room differently according to the orientation towards the sun, the height of the ceilings and the shape of the spaces.

He also designed a sort of hole in the façade, a nod to the work of the artist who is currently very present in people’s minds, Gordon Matta-Clark (1943-1978).

The installation of the artworks themselves is elegant since it leaves a lot of space between the works.

This pace belies a deliberate act of selection given that we know that at Prada they have been buying a lot over many years.

The placing of the artworks has been the fruit of lively discussions between Miuccia Prada and Germano Celant, who has advised her for many years on various purchases.

Celant explains how it was organized in dialogue with the architecture of the tower.

The most extraordinary room is not the largest.

It is a specific installation by the German artist Carsten Höller (born in 1961). An entire room is filled with giant mushrooms hung upside down from the ceiling, which rotate on their base. Höller has managed to externalize hallucination. It isn’t our head that is spinning, it’s these supernatural fungi.

More broadly, the principle of the exhibition requires the cohabitation of two artists per floor, giving rise to unexpected “couplings”.

Yet the surprise here is the fact that in such an unconventional space, two “market-friendly” artists take pride of place: Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons.

Hirst is often criticized for failing to produce much that is new since his early work and at the Prada foundation the majority of his pieces, which are very radical and of a good quality, date unsurprisingly from the 1990s, such as “Tears for Everybody Looking at You” (1997), a huge glass-cased aquarium in which a duck, which looks real, gliding on the water is sheltered from the rain by an umbrella.

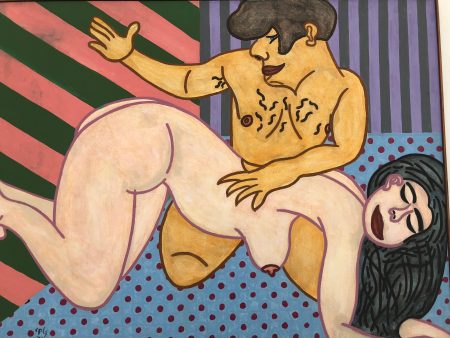

Hirst is accompanied here by colourful, caricatural, porno-esque paintings from the 1970s by the American artist William N. Copley (1919-1996).

Jeff Koons is also present, with a very shiny and very large bouquet of tulips dating from 1995-2004.

Here again Germano Celant tells us that the artwork “was bought early on, at a time when the artist was bankrupt and could no longer find buyers. We follow artists in the long term.”

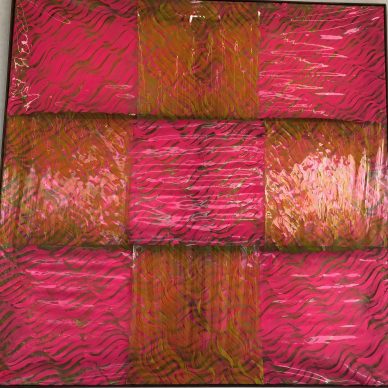

Koons is placed in dialogue with Carla Accardi (1924-2014), an artist who is legendary in her native Italy for her feminist activism and her abstract work using new plastic materials.

The installations of the three gleaming red Chevrolet cars pierced by steel rods by Walter De Maria (1935-2013) are a hymn to the beauty of the automobile by the bard of Land Art. Coincidentally, Dia Beacon is also exhibiting cars by De Maria.

Of time and space, these atypical artworks are by artists who will make their mark on history. This is where the great minds of contemporary art think alike.

(1) For those who are not familiar with it, this exemplary institution in the Hudson valley, a former printing plant only an hour and a half from New York by train, reserves a great deal of space for sculptures and installations (a lot of American art and a lot of minimal art) and also for the empty space around them. The programme there changes every few years.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.