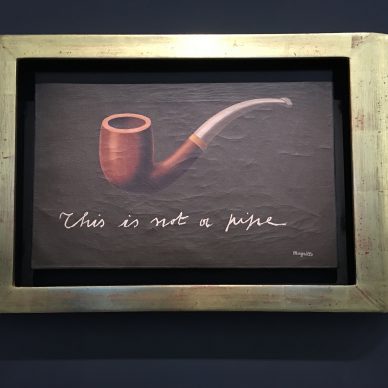

René Magritte (1898-1967), who painted the pipe in 1929 accompanied by the famous line ‘ceci n’est pas…’ or ‘this is not…’ has earned his place in the collective imagination on the basis of this work.

But with ‘Magritte, The Treachery of Images’ at the Pompidou Centre, curator Didier Ottinger has pulled off a miracle by establishing the intellectual foundation to this Belgian surrealist who we’ve come to associate with a sense of trivial strangeness.

The exhibition’s premise is that Magritte was inspired by philosophy.

Ottinger takes his cue, among other things, from a 1968 essay by Michel Foucault, which discusses the contradiction and the disquiet that the famous pipe painting elicits.

He explains:

It is a bold premise but it has a merit: through this quite exhaustive hanging (around a hundred works) we’re given the chance to rediscover the eccentric painting of one of the great precursors of contemporary art.

The New York-based modern art dealer Emmanuel Di Donna gives his verdict on the exhibition:

Magritte’s association of ideas, his association of words and images, and his desire to produce a flat painting, with no depth, are at the origin of Pop Art among other things. Bear in mind that René Magritte, like Warhol, plied his trade in advertising before making a living from his brush.

Didier Ottinger explains why this exhibition, even taking a philosophical angle, does not pass over important pieces in Magritte’s oeuvre:

The first room, in which works encompassing all periods and themes are magisterially combined, compels the viewer to face the facts. Both before the war and even after it, when Magritte is thought of as a commercial painter answering to the diktats of his American dealer Alexandre Iolas, he implements innovative visual codes.

Any examples? ‘Time Transfixed’ is a canvas from 1938 that represents a bourgeois interior featuring a fireplace and a clock on the mantelpiece, which is pierced by a miniature locomotive puffing smoke.

‘The Anger of Gods’ from 1960 shows a jockey on his mare galloping over the roof of an old car against a mountain backdrop.

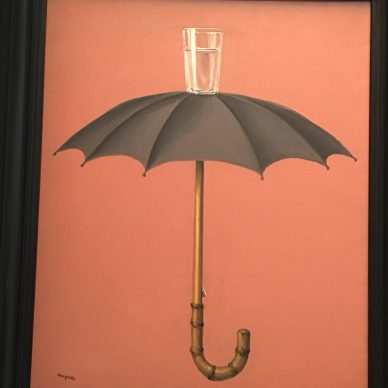

And ‘Hegel’s Holidays’ from 1958 shows an open umbrella with a glass full of water balanced on its top.

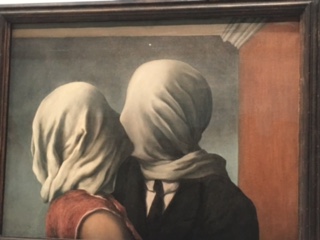

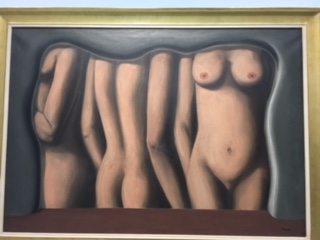

In the section dedicated to history, Didier Ottinger highlights a passage by the first-century Roman author Pliny the Elder in which he describes painting as being like love with its betrayals; in other words, it is unable to reproduce the real. It is in this spirit that ‘The Lovers’ (1928) shows a man and a woman on the verge of a kiss but their heads are covered with a cloth.

The same year, ‘Attempting the Impossible’ represents the painter himself giving form, with the help of his paintbrush, to a woman in three dimensions.

Magritte is a master, the great master of his fantasies, turned into images.

Charlie Herscovici, at the head of the Magritte Foundation and a great character of the art market, ends with the following thoughts first in french and finally in english:

Until 23 January. www.centrepompidou.fr

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.