The masterpiece “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon”, Picasso’s cubist manifesto now on display at Moma, doesn’t depict pretty girls from the south of France but rather creatures concealing very little of their physicality plying their trade in a brothel on Avignon Street, Barcelona.

The other artwork was made by Giacometti, whose idea for most of his elongated, distant, ghostly figures arose after he saw, again in a brothel, the young ladies who worked there presenting themselves to their clients.

For a long time, in fact, prostitution in brothel houses served as a source of inspiration for artists. Gauguin, Van Gogh or Toulouse-Lautrec were also known to frequent such places

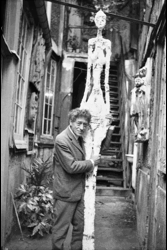

But to return to our subject, Alberto Giacometti was one of the most diligent practitioners of this aesthetic employment of prostitutes.

In the intriguing biography published by Catherine Grenier (1), director of the Giacometti Foundation, the issue is clearly evoked: “The first woman I had been with was a prostitute. It suited me.

The idea of love, this sticky, ambiguous mixture of feelings and physical gestures, had always disturbed me (…) That’s why when I was 25 I found it unbearable to spend the night with a woman I loved. But at the Sphinx, which for me was the most wonderful place, we weren’t obliged to go upstairs. We could stay in the main room chatting with friends”.

Art, great art, has nothing to do with the narrow crucible of politically correct ideas.

People are keen to present Giacometti as a sterilized artist who elegantly furnishes the interiors of billionaires, when he was in fact a complex being.

There are currently several opportunities around the world that might afford us a better understanding of this unconventional figure.

Until 2 September the Beyeler Foundation is showcasing a subtle and unexpected dialogue between two monsters of twentieth-century art, the Irish artist Francis Bacon and the Swiss sculptor himself. Both artists depicted the human figure and its torments. Both also envisaged the human figure encaged.

From 8 June the Guggenheim in New York is dedicating almost the entirety of its space to Alberto Giacometti.

Catherine Grenier (co curator of the show) explains how Giacometti first gained recognition in the United States, where the art dealer and son of the painter, Pierre Matisse was working. His first exhibition at the Guggenheim dates from 1955 and Moma first purchased his work in the 1930s. A third of the exhibition will be comprised of major works never before displayed in the United States.

Catherine Grenier discusses the Guggenheim exhibition:

On 22 June the Institut Giacometti (350 m2) is due to open in Paris, whose principal virtue will consist of reconstructing the 23 m2 of the remarkably modest studio in the 15th arrondissement where Alberto lived from 1926 until his death in 1966.

He always refused to leave it, even when he had the means to do so and even though there was no kitchen or hot water.

The entire contents of the studio have been preserved, including the walls with their drawings of ghostly figures that his wife Annette managed to recover.

Catherine Grenier explains the reasons behind the creation of the Institut Giacometti:

According to Catherine Grenier, the Giacometti foundation currently has a collection of 2000 drawings and prints, 350 sculptures many of which have been restored from plaster, 90 paintings, 100 sketchbooks, over 2000 photos and his entire correspondence.

When the writer Jean Genet visited Giacometti’s studio in the 1960s he emerged almost dumbfounded: “when I left the studio, at that moment nothing around me seemed real anymore”.

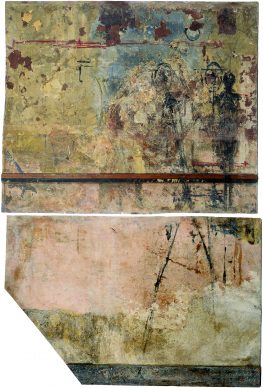

When describing his work from this later period, Genet talks about “this secret place, this solitude where beings – and things too – could take refuge”.

And again: “This afternoon we are in the studio. I notice two canvases of an extraordinary acuteness, they seem to be moving, coming forward to meet me”.

And now here they are, on the move from Basel, to New York, to Paris.

(1) Alberto Giacometti. A biography. Catherine Grenier. Flammarion.

Donating=Supporting

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JBH Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.