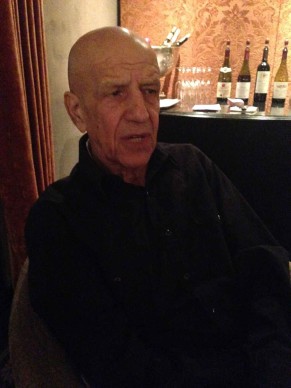

I met Alex Katz one evening in February 2014 in Paris, in his Place des Vosges hotel room. Born in 1928, the Pop Art painter looks incredibly youthful and cool. He laughs a lot. He smiles a lot, and marks a pause to watch you react to something provocative he’s just said. He’s part of the posterity that American art established earlier, in the 1960s. His works are like tiny scenes, stop-motion pictures of a rather preppy and white segment of American society. His paintings also seem to come out of an imaginary theater that has gone through the wringer of television.

Our conversation begins with digressions about the appearance of women in the U.S. Katz observes that French women are very elegant, whereas American women look like clichés found in magazines and don’t mind looking exactly like each other. He also notes that British women choose style over elegance, and that Russian women, like their Italian counterparts, want to appear sexy above all. The tone is set. Alex Katz likes to cultivate what is futile.

How did he become an artist? Thanks to his neighborhood and through a process of elimination. He studied violin, which he dropped to run track, and in his new Queens “suburb” in the 1930s, he met two young artist neighbors who spurred him along the path of art. He drew all the time, and eventually got into the famed Copper Union School of Art. “I didn’t have any talent but I became a great artist,” Katz says with a mitigated lack of modesty. At the time, Cubism was in vogue at Copper Union, but Katz’s discovery of Jackson Pollock turned him upside down. “It completely exploded that Cubism idea,” he says. “My goal was to find what was realistic. People don’t see art through their eyes; they see it through their culture,” he continues. “Me too. I am inside our culture. But I was trying to do something new. There were huge billboards, magazines, television, advertising.”

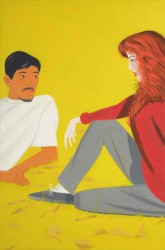

In the 1950s, Katz confesses, the artist destroyed about 100 of his paintings, until he reached what he calls “a new vision, a new painting.” “The ’50s were very hard,” he says. “I was living on $18,000 per year. No clothes, no dentist, no medical care, no family. But parties, parties!” Toward the end the ’50s, Katz says he understood that, as he puts it, he was “there.” The scenes he was beginning to paint and that would recur throughout his career showed landscapes, flowers and, above all, men and women painted on the spot. The colors were bright and contrasted. Katz says that he’s not interested in color, but rather in light, and that color is only a means through which he can get at it.

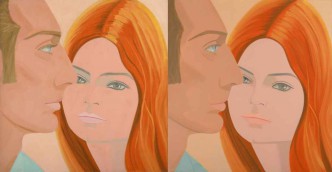

As far as his characters are concerned, his intent is not to show us their souls, or any kind of interiority, but rather to truly show us their appearance. In that, he’s very Pop, as if he could represent the world in some sort of TV movie. “I like appearance, not interiority,” he says. “Feelings are so scary. When people tell you they feel like expressing themselves, you’re in for a terrible evening. When you ask art school students to express themselves, you’re killing their vocation.” Still, Katz doesn’t deny his paintings contain a certain dramatic intensity.

The artist says he works everyday, either drawing or painting. “But you have to establish a series system, otherwise you’re always painting the same thing over.” Katz uses as an example one of his recent subjects, a close-up of a tree taken in front of his house in the country. The blue of the sky; the green of the tree. He painted it twice in a small format, and his wife said that it was good. So he painted it again in a larger format. “A good painting should be done in two hours,” he says. “I prepared everything. I drew on the canvas. I put the different-size brushes I needed next to me.”

He admits that he now rarely destroys his paintings. “I have perfect technical mastery nowadays,” he explains. How does he choose his models? “I don’t have any explanation for that. Among my latest choices were employees of the Gavin Brown gallery where I was having an exhibition,” he notes, adding: “The image I create has to stay in people’s minds. It has to include a bit of aggressiveness.” Among his influences, Katz cites modern painters like Matisse, but also the Japanese artist Utamaro, a master practitioner of the ukiyo-e genre of woodblock prints, who “painted Bohemia, like me.” It should be noted that, like Katz, Utamaro presented flat scenes without volume.

If you’d like to have your portrait painted by Alex Katz, the master will show himself to be demanding or—more precisely, let’s say—animated by a keen business sense. “It’s demanding work, so he [or she] should already own two of major works by me and pay double for the portrait.” Nowadays, the artist paints about 50 works per year. He admits he’s in no rush to sell them either: “Some paintings waited 30 years before they found a buyer or a public space.”

Donating=Supporting

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JBH Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.