He doesn’t display the usual rigidity during interviews. I met him last year and the man was all smiles, speaking to me at length about boxing and his “clashes” with artists and clients within the architectural discipline. He himself was a boxer in a previous life.

It’s therefore no coincidence that the exhibition currently dedicated to him at the Centre Pompidou is called “the challenge” (« le défi »). But this time we see Tadao Ando in a more serious light. On the occasion of the opening dinner he relates his desire to live for at least another 20 years, his desire to finish his construction at the Bourse de Commerce in Paris, but he also points out that he has had to have five vital organs removed.

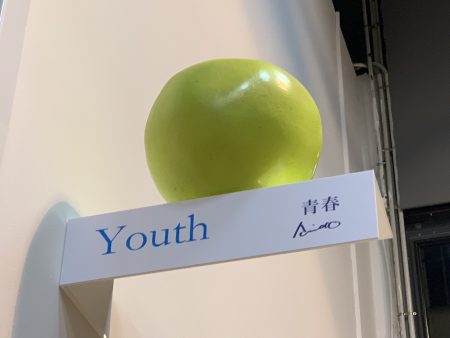

At the last minute he had a large green artificial apple installed at the entrance to the exhibition, a symbol of longevity. Also at the last minute, he took great care to make drawings in marker on the plinths for the models of the different projects exhibited.

In the film that accompanies the exhibition, he doesn’t elaborate grand theories on his creations. He prefers to keep things at a human scale, saying for example: “I want people to be proud of the creations that I’ve made for them.”

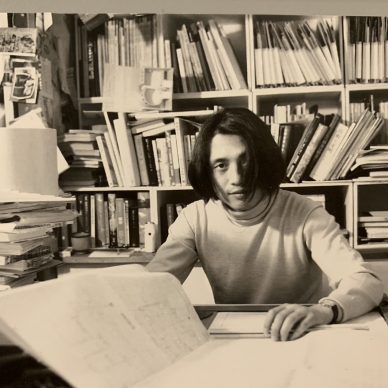

His team in his studio in Osaka, which has been based in the same building since 1969, is comprised of just 25 people working together with a very family-like approach, according to the curator of the exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, Frédéric Migayrou. 25 people for no less than 250 projects completed around the world, some of which, as we can see in the exhibition, are colossal in size.

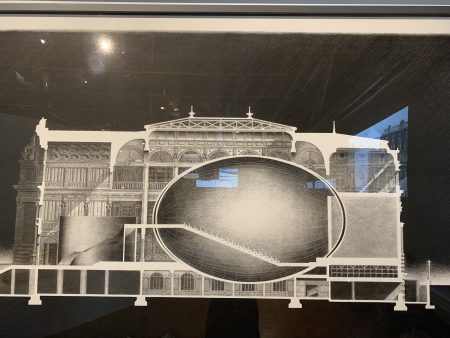

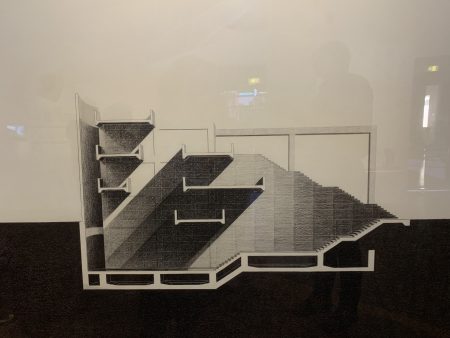

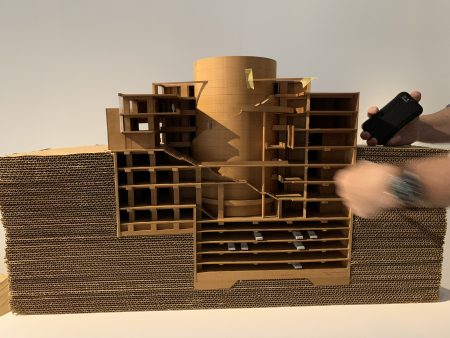

The project that seems closest to his heart right now is the Bourse de Commerce, due to open next year to house the collection of French businessman and owner of Christie’s François Pinault.

A gigantic model of the building is displayed at the Pompidou among the 49 other projects exhibited.

Contrary to what might be believed, as pointed out to us by the director of the Fondation Pinault Martin Béthenod, this three-dimensional creation matches the very first draft of Ando’s dream for the place. The scales have not been respected. The architect, in his first draft, doesn’t like to be confined by technical obligations.

Which leads us to say that Ando’s brain seems primarily to function like that of an artist.

Incidentally, at the beginning of his career he was associated with the group of visual artists who were particularly active in terms of performances, Gutai (cf. the blog on this subject).

This experience has definitely had a major influence on him in terms of the relationship between the body and space.

Ando draws a lot, creating freehand virtuoso pieces with sketches of his projects but also of memories of his travels during his youth, like the Cistercian abbeys celebrated by Le Corbusier, the ultimate reference point for Tadao Ando.

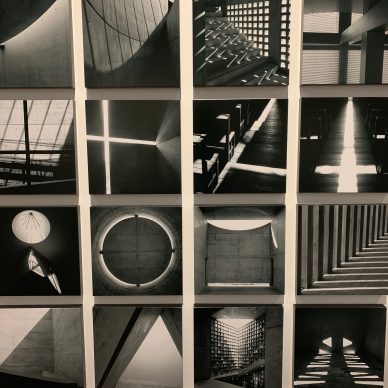

He is also the photographer for his projects and in this respect he is reminiscent of Brancusi.

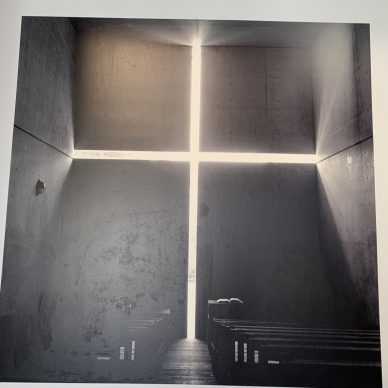

This is where a major component of his work enters: light.

Two other famous architects, Jean Nouvel and Renzo Piano – like him both winners of the Pritzker Prize and builders of museums – talk about their Japanese fellow architect.

Jean Nouvel:

Renzo Piano:

Tadao may be a fan of light, but he is also an architect who burrows, one who attacks the mountain to unearth his constructions.

The most extravagant work of this kind is “The Hill of the Buddha” made between 2012 and 2015 at Sapporo on the island of Hokkaido. Ando had the idea of concealing a giant buddha (13.5 metres high) erected 15 years earlier by constructing a mound reaching up to the top of its head covered with 150,000 lavender plants.

While Tadao is known for his concrete walls, which delimit spaces but reflect the light thanks to their polished surface, he is also keen on empty spaces to promote air circulation and brightness. According to Frédéric Migayrou he applies the principle of Shintai from Shintoism, according to which objects and natural elements are used as mediums for worship.

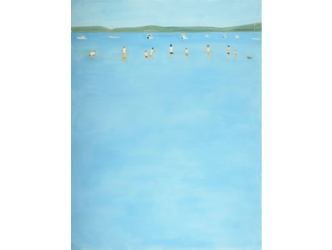

The work that takes pride of place in the exhibition, which applies his favourite principles, is Naoshima, nicknamed the museum island, in the South of Japan (see the blog on the subject).

Soichiro Fukutake, the businessman who made his fortune from correspondence courses and who is behind the Benesse Island project on Naoshima, was present at the opening.

He seemed particularly proud of the important space accorded to Naoshima at the Centre Pompidou.

The Tadao Ando exhibition in Paris presents a paradox. It is abundant and therefore interesting, thanks to the number of drawings, models and videos illustrating the 50 projects selected by Ando.

But it is precisely this abundancy which fails to convey the core principle of this architect-artist: a thoroughly pared-back style, a sophisticated starkness.

There’s nothing else for it, you’ll just have to go and visit his buildings.

Until 31 December: www.centrepompidou.fr/cpv/resource/cdAkgz5/rMgAEp7

Donating=Supporting

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JBH Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.