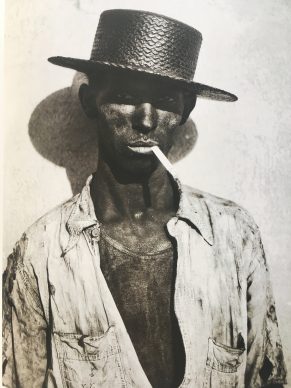

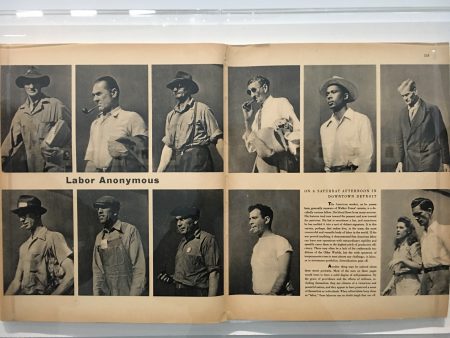

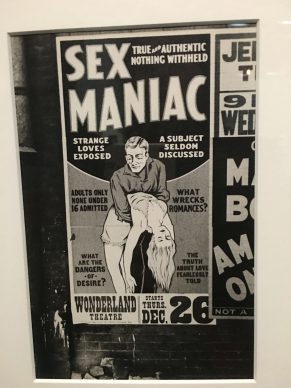

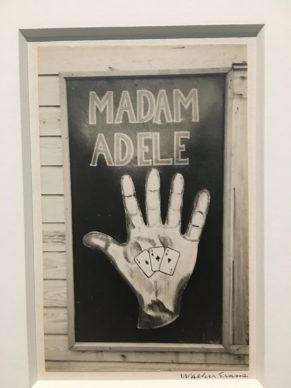

Take the American photographer Walker Evans (1903-1975), one of the very big names in world photography, someone who in the 1930s was throwing himself into a new genre we refer to nowadays as ‘vernacular photography’.

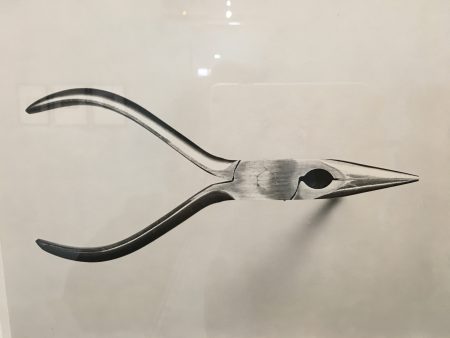

During the same period the entire international photography scene from Alexander Rodchenko in Russia to Germany’s Germaine Krull who lived on-and-off in France appeared to be flirting with abstraction: think geometric shapes, metal structures and light effects. Across the Atlantic,Evans, inspired by the french great photographer Eugene Atget (1857-1927) would confront everyday details head-on: people in the street, signs, real life.

Much later in his career, in 1971, he declared that he was addressing those people ‘capable of fully appreciating the value of things, without being subjected to inhibitions linked to public decency.’

Fast-forward to today and trends have moved on, with vernacular photography now acclaimed, even in the work of unknown photographers.

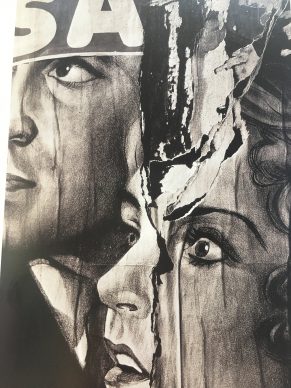

WalkerEvans forged a path for the rest of the art history, including Pop Art, by bringing into focus objects from an incipient consumer society.

At the Pompidou Centre, the Evans retrospective presenting 400 prints and documents (it could have benefited from an edit) shows implacably and for the first time how the artist’s creative bedrock is this idea of ‘popular’ subjects. The exhibition’s curator Clément Chéroux (previously at the Pompidou Centre, currently at the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco) has created an excellent thematic show that includes a plethora of objects collected byEvans including commercial signs as well as stark, beautiful small-format paintings on the same theme.

Clément Chéroux described the idea behind the show.

All the Walker Evans archives are on loan from New York’s Metropolitan Museum, which acquired them in 1994.

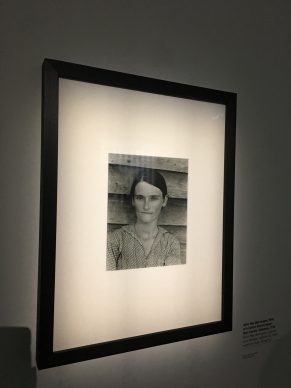

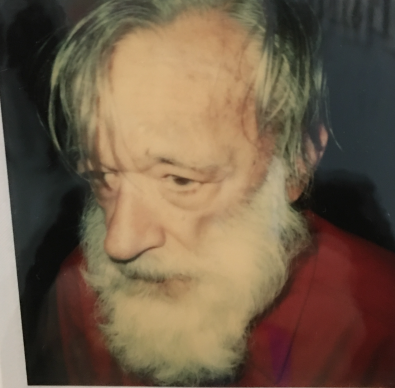

Between 1935 and 1937 Evans photographed the Great Depression through families of farmers, resulting in the series ‘Three Families in Alabama’. The prominence given to this series undoubtedly obscures the overall coherence and tenor of his work.

It includes the portrait of the wife of a sharecropper, Allie Mae Burroughs.

This close-up of a seemingly toothless woman dates from 1936 and exemplifies a kind of secular Madonna, a martyr of capitalism. For the purists, the Pompidou Centre has two slightly different versions of the shot. Thanks to Walker Evans this poor woman wearing a gloomy look of resignation has become both a star and icon of twentieth-century photography.

Until 14 August, www.centrepompidou.fr

The exhibition will be held at SFMoma from 30.09.2017 to 04.02.2018

Donating=Supporting

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JBH Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.