Andy was a child of the television generation. He was born on the 6th August 1928 in Pittsburgh, just two years after the Scotsman John Logie Baird put the final touches to the initial “televisor” that was to be distributed throughout England from 1930 onwards. In the Western world, post-War, owning a television represented a sign of social achievement. The child who was still then known as Andrew Warhola came from an extremely poor Pittsburgh family, and we don’t know at what date he actually had access to this cult object of capitalistic American society. Yet we have his own account of the experience : “on my way back from the psychiatrist, I stopped at Macy’s, and on a sudden impulse, I bought my first television set (…) I left the television on the whole time, particularly when people were talking to me about their problems, and I realized that television diverted my attention just enough so that the problems that people were telling me about didn’t affect me any more. It was like this magical thing”.

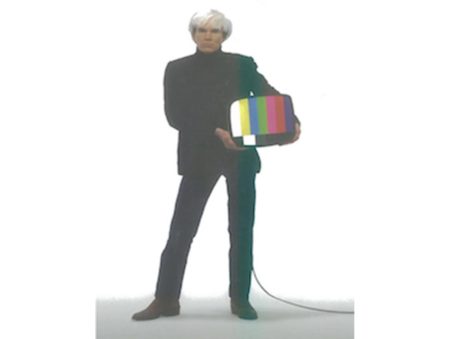

Andy, an entrepreneurial all-rounder, who produced paintings– based on the principle of repetition, even if they were always one-offs- a rock group, a play, books, a cultural events magazine, also wanted to produce his “magical thing”: his own television.

In modern society the invention of television was swiftly followed by a number of vital accessories, such as TV chairs, or TV lamps. There were to be TV artists deliberately created as television personas. The one who outstripped them all in terms of his determination in the field was Andy Warhol.

Specialists reckon that the real explosion of the impact of television dates from the assassination of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy on the 22nd november 1963. So much better than a movie, the most powerful man in the world – and one of the most charismatic – was killed in full view of onlooking amateur cameras. Spectacular. Andy, the spectator, the television spectator, the voyeur, was right there in his own way. He understood the impact of the images and produced painted portraits of the First Lady of the United States, who was wearing such a pretty pale pink hat that day.

Television is better than the cinema because you believe it.

Television is “reality”. The best possible script.

Andy Warhol didn’t fake it. The Pop artist loved pop(ular) television.

In an article published in Esquire magazine in 1975 in which he listed his twelve favorite TV programs, he cited “I love Lucy” in good place. It was one of the first sitcoms ever aired, which started in 1951, but that has never been off American television screens since, despite the fact that the last episodes date from 1957. (It was first aired on French television as late as 1999). Warhol wasn’t without knowing that the two main actors in the series, a couple, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, were also a couple in real life. “Desi Arnaz is in real life the conductor of a Latino band, and became Ricky Ricardo, Latino conductor. Lucille Ball, a well-known actress, became a house-wife who dreams of an acting career. The sitcom moulded itself on the actors lives. When Lucille Ball gave birth, the day’s episode dealt with Lucy giving birth. And the child then became the third character”(2). For his own television Warhol did the same thing. Friends drop by at the Factory for lunch? They’re filmed. Lisa Minelli comes to see her portrait. She’s on screen. Paloma Picasso makes a new range of jewelry for Tiffany’s? Bring her into the studios and ask her about her dad. Say! Warhol has a gym coach. He can do press-ups on screen…

Just like in his early films ,”Sleep” or “Empire”, if he could, Andy would have had the camera rolling non-stop, just like he would leave his tape-recorder on, taping conversations in the Factory even after he’d left (see the interview with Glenn O’Brien. Sitting down and asking questions of the people who were passing through.

It was the reality television of Warhol’s world.

Television is better than cinema because it’s more immediate. John Giorno, a friend of Warhol’s from the early days, expresses that clearly in his interview.

And another good thing about television is that it’s on all the time.

In the 1950s, the film-maker Jean Renoir, son of painter Auguste Renoir declared “I must say that the television shows that have fascinated me the most are certain interviews that I have seen on American television. It seems to me that interviews give television a sense of the close-up that only very rarely exists in cinema (…) In my view, American television is admirable. Extremely rich. Not because it’s the best or because the people have more talent than in France, but quite simply because in a town like Los Angeles, there are ten channels that are constantly functioning, at any hour of the day or night.”

Warhol is a child of American television.

But Warhol is also the heir to several artists from the European culture. Jay Shriver, one of Warhol’s last assistants, is the only one to make reference to Cocteau when he speaks of him. “He wanted to be the new Cocteau” . He wanted, like him, to write, to draw, to make films. In 1940 Jean Cocteau had signed the script of a film by Marcel L’Herbier “La comédie du bonheur”(Comedy of happiness). It starts with the simulation of a TV program. In 1964 Andy Warhol also imagined a fake TV show with “Lester Persky”. In it we see a silent sequence of a sentimental film with no actual story-line, interspersed with real television adverts, with sound. Lester Persky was the name of the television producer who gave him the adverts.

The important thing is the adverts, with their hard-hitting messages, like: “Mummy you don’t have to worry about body odor any more”, The reality of television. Reality television.

Warhol was also the spiritual son of the former surrealist Salvador Dali. He met him. He even filmed him twice in 1966 in one of his “Screen tests”. These filmed portraits consisted of a sequence several minutes long in which the camera filmed the person in one fixed shot. Warhol had no tabous and willingly took part in the sort of operations that artists usually turned down, such as adverts or television shows. But Dali had done that before him. He had collaborated on cartoons with the Disney studio, as well as several films, such as Luis Bunuel’s “An Andalusian Dog” in 1927, a project with the Marx Brothers in 1937… He had created a (short-lived) newspaper, Dali News, in 1945. At the same time as Warhol, he did the advert for the Braniff airline company in 1969, and one for Lanvin chocolate in 1970, and yet another for the automobile makers Datsun in 1972.

Andy was, however, two years ahead of him on one thing. He did the cover of TV Guide ( the “legendary” American magazine devoted to TV programs) in 1966, in the purest Pop style. Dali did the cover of the same magazine in a post-surrealist style in June 1968. And then Dali didn’t create his own television…

But if Warhol is the spiritual son of anyone, it’s of another giant of art history: Marcel Duchamp. This last had his portrait done in “screen test” mode three times by Warhol in 1966 at Pasadena. Duchamp was opening a exhibition in the small Californian town. He invited Andy along and this last had a project to do an on-going film of Marcel Duchamp. “It was just an idea. I did a few shots, but not much really. A few cuts of 16mm film. But the project would have got made if we had found someone or some foundation to finance it. As I made films that were twenty-four hours long (Empire,1964) I thought that it would be really great to film him for twenty-four hours” “I like Warhol’s spirit” Duchamp declared at the time. Like him he didn’t want to be what polite society calls “a fine artist”. His creativity needed to express itself outside the usual fields. Benjamin Liu, assistant at the Factory, explains (cf pXXX) that the question isn’t one of whether or not Warhol’s television was art. “Warhol is art”.

But one must recognize that what is the most unsettling in Warhol’s television is the fact that the artist made TV programs that are real TV programs. At the same period, other artists were also “attacking” television, but in a militant way. In a program officially dating from 1973 but that was in fact made at an earlier date, Richard Serra and Carlota Fy Schoolman made a video called “Television Delivers People”. It’s a written message, in a minimal style that is particularly anti-media. In 1983 Bill Viola imagined a program made up of forty-four portraits of television spectators that would be broadcast without any further commentary between the usual programs on a Boston TV channel. Initiatives by artists usually seek to break the normal flow of classical TV. Warhol, on the contrary, played the media game. With him we find information and even practical information such as “how to put on your make-up” but also new faces, new sounds, a seductiveness, celebrity. If w e keep in mind who Warhol was, it was in fact his way of doing “ready made” television programs.

Warhol’s initial intention, when still at the stage of actually doing television, had been to call his show “Nothing special”. Nothing special, in effect. It’s only television. But television as done by Andy Warhol.