“On Air” – The expression is one we commonly use for programs that are broadcast on television: “to be on air”. No other words could be better suited to Andy Warhol. He liked to reproduce reality, even if as a travesty. […] What did Andy Warhol want to flaunt? His own era. For, at the end of the day, Warhol didn’t show much of himself on his TV. What he showed was his world.

Andy Warhol was a child of the television generation. He was born on the 6th August 1928, just two years after the Scotsman John Logie Baird put the final touches to the initial ‘televisor’ that was to be distributed from 1930 onwards. In the Western world, post-War, owning a television represented a sign of social achievement. Warhol came from an extremely poor Pittsburgh family, and we don’t know at what date he actually had access to this cult object of capitalistic American society. Yet we have his own account of the experience: ‘on my way back from the psychiatrist, I stopped at Macy’s, and on a sudden impulse, I bought my first television set […] I left the television on the whole time, particularly when people were talking to me about their problems, and I realized that television diverted my attention just enough so that the problems that people were telling me about didn’t affect me anymore. It was like this magical thing’.

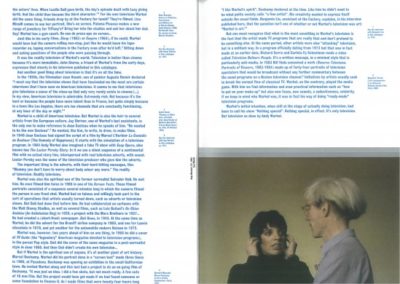

In an article published in Esquire magazine in 1975 in which he listed his twelve favourite TV programs, he cited I Love Lucy in good place. It was one of the first sitcoms ever aired, which started in 1951, but that has never been off American television screens since, despite the fact that the last episodes date from 1957. Warhol wasn’t without knowing that the two main actors in the series, a couple, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, were also a couple in real life. […] The sitcom moulded itself on the actors’ lives. […] For his own television Warhol did the same thing. Friends drop by at the Factory for lunch? They’re filmed. Lisa Minelli comes to see her portrait. She’s on screen. Paloma Picasso makes a new range of jewellery for Tiffany’s? Bring her into the studios. Say! Warhol has a gym coach. He can do press-ups on screen…

Just like in his early films, Sleep (1963) or Empire (1964), if he could, Warhol would have had the camera rolling non-stop, just like he would leave his tape-recorder on, taping conversations in the Factory even after he’d left. It was the reality television of Warhol’s world. […]

But one must recognize that what is the most unsettling in Warhol’s television is the fact that the artist made TV programs that are really that and don’t pretend to be something else. At the same period, other artists were also ‘attacking’ television, but in a militant way. Initiatives by artists usually seek to break the normal flow of classical TV. Warhol, on the contrary, played the media game. With him we find information and even practical information such as ‘how to put on your make-up’ but also new faces, new sounds, a seductiveness, celebrity. If we keep in mind who Warhol was, it was in fact his way of doing “ready-made” television programs.

Warhol’s initial intention, when still at the stage of actually doing television, had been to call his show Nothing Special. Nothing special, in effect. It’s only television. But television as done by Andy Warhol.

Andy Warhol was a child of the television generation. He was born on the 6th August 1928, just two years after the Scotsman John Logie Baird put the final touches to the initial ‘televisor’ that was to be distributed from 1930 onwards. In the Western world, post-War, owning a television represented a sign of social achievement. Warhol came from an extremely poor Pittsburgh family, and we don’t know at what date he actually had access to this cult object of capitalistic American society. Yet we have his own account of the experience: ‘on my way back from the psychiatrist, I stopped at Macy’s, and on a sudden impulse, I bought my first television set […] I left the television on the whole time, particularly when people were talking to me about their problems, and I realized that television diverted my attention just enough so that the problems that people were telling me about didn’t affect me anymore. It was like this magical thing’.

In an article published in Esquire magazine in 1975 in which he listed his twelve favourite TV programs, he cited I Love Lucy in good place. It was one of the first sitcoms ever aired, which started in 1951, but that has never been off American television screens since, despite the fact that the last episodes date from 1957. Warhol wasn’t without knowing that the two main actors in the series, a couple, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, were also a couple in real life. […] The sitcom moulded itself on the actors’ lives. […] For his own television Warhol did the same thing. Friends drop by at the Factory for lunch? They’re filmed. Lisa Minelli comes to see her portrait. She’s on screen. Paloma Picasso makes a new range of jewellery for Tiffany’s? Bring her into the studios. Say! Warhol has a gym coach. He can do press-ups on screen…

Just like in his early films, Sleep (1963) or Empire (1964), if he could, Warhol would have had the camera rolling non-stop, just like he would leave his tape-recorder on, taping conversations in the Factory even after he’d left. It was the reality television of Warhol’s world. […]

But one must recognize that what is the most unsettling in Warhol’s television is the fact that the artist made TV programs that are really that and don’t pretend to be something else. At the same period, other artists were also ‘attacking’ television, but in a militant way. Initiatives by artists usually seek to break the normal flow of classical TV. Warhol, on the contrary, played the media game. With him we find information and even practical information such as ‘how to put on your make-up’ but also new faces, new sounds, a seductiveness, celebrity. If we keep in mind who Warhol was, it was in fact his way of doing “ready-made” television programs.

Warhol’s initial intention, when still at the stage of actually doing television, had been to call his show Nothing Special. Nothing special, in effect. It’s only television. But television as done by Andy Warhol.