This story begins, for me, in 2006 or early 2007 in the lobby of a London hotel.

Tom Krens was head of the Guggenheim at the time, a museum he sought to transform into a global brand.

He had opened branches of the establishment in downtown New York, Bilbao, Las Vegas, and tried to open a site in Mexico, and northern Europe, along with many other ventures.

On that morning this man, an enthusiast who often tells stories of his wild outings on motorcycles in the company of his biker friends and actors like Jeremy Irons, outlines a project to me that he had designed at the request of the government of the United Arab Emirates.

For Abu Dhabi, he imagined a museum island, Saadiyat, a few hundred metres from the country’s capital, modelled slightly on Venice (the presence of water) but also reproducing the Bilbao effect (big architecture associated with a big institution).

At that time, oil is expensive and flows abundantly.

There were terrorists of Emirati origin involved in the twin towers attacks and the Sheikh Khalifa at the head of the Emirates, like the former ruler, his father, Sheikh Zayed, ‘founder of the nation’, were shocked.

Sheikh Mohamed himself, head of Abu Dhabi and brother of Sheikh Khalifa swears by soft power, education, and so he asked Tom Krens, the great specialist in creating museums from scratch, to envision for his country a project worthy of the pharaohs.

That morning, Tom Krens and myself had only just woken up, and I struggled to envision his new Venetian-Hispanic-Middle-Eastern utopia.

On Saadiyat Island, he proposed to create a Louvre designed by Jean Nouvel, a colossal Guggenheim designed by Frank Gehry, but also further establishments by Tadao Ando, Zaha Hadid…

And he showed me the designs on his computer.

Almost eleven years later, it transpired that Tom Krens had been right about one thing at least on that morning .

For on 11 November 2017 the Louvre Abu Dhabi will open its doors to the public.

Today, Tom Krens is no longer the head of the Guggenheim. He has a somewhat unrealistic museum project underway in Massachusetts.

Today, without even a mention of the other projects, and despite the acquisitions that have already been made for its permanent collections, work on the Guggenheim of the sands seems to have stalled.

Frank Gehry, whom I have just interviewed (available to read soon on JBH reports), confesses that he hasn’t heard from anyone in Abu Dhabi for a long time.

But against all odds, the French project led by a consortium of 17 museums (and not just the Louvre, contrary to what the leasing of the “Louvre” name would imply, for 30 years and 400 million euros) has successfully seen the light of day.

The Louvre Abu Dhabi projet won and exists primarily for two reasons.

The first is that the project has been the object of a 2007 intergovernmental agreement with 320 obligations established from State to State.

The second is because, in order to avoid the huge administrative burden, the organizers of this long-term plan on the French side created a private company from scratch, France Museums, bringing together the 17 participating museum administrations.

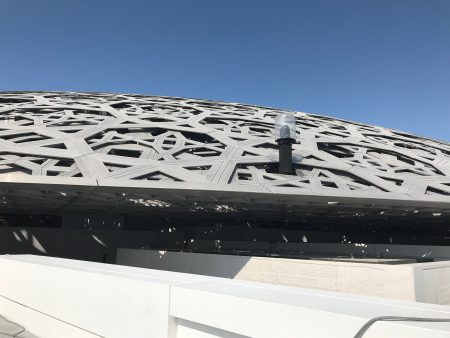

The result is, first and foremost, architecturally spectacular.

Jean Nouvel has certainly created his masterpiece. A cupola measuring 180 metres in diameter composed of 8 layers of latticework in the shape of modulable stars arches over a series of 55 cubes, like giant houses containing the museum’s exhibits.

There is a quasi-celestial quality to this vaulted space, which has a magical effect on the visitor.

“It’s our Eiffel tower” says an Emirati businessman.

Jean Nouvel explains the idea behind the cupola structuring his building.

The idea that brought this museum into being is universality. It’s a big word for a titanic task, above all for France, who has long been guilty of ethnocentrism.

But if all men believe in something, feed themselves, raise their children, gain power, travel, discover, and die, we can find, from Africa to Oceania and from Europe to China, objects that tell the story of these evolutions, but which also bear testament to their unique aesthetic expression.

Today, the Louvre Abu Dhabi, which has an annual acquisitions budget of 400 million euros, heads a collection of 620 objects, of which 300 are exhibited.

They are supplemented in the universalist fashion by 300 pieces on loan from the 17 French museums, 100 of which come from the Louvre. (French museums such as the Musee d’Orsay, Musee Rodin and Branly etc have received in total 190 million euros for the loaning of artworks).

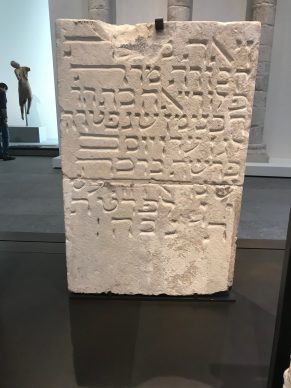

Here one can find, among others – and it is an excellent surprise in a Muslim country – sculptures of nudes, sculptures of Christ and the Madonna, religious documents in Hebrew: everything, or almost, that should have posed a problem.

The president of the Louvre Abu Dhabi, Mohamed Khalifa al Mubarak, is from the UEA. I asked him what he thinks of the idea of Universality.

The collection was set up by Jean-François Charnier, the scientific director of the operation. He elaborates on his idea of universality.

During the too long opening speeches, there was one phrase of great importance that stood out, spoken by the president of the Louvre, Jean Luc Martinez:

“This museum is a message of openness in a period of fanaticism.”

It’s certainly the most exciting thing presiding over the opening of this establishment.

For one year, the Louvre has loaned one of its absolute treasures, “La belle ferronière” by Leonardo da Vinci.

Inside the galleries there is an accelerated journey through time and space.

It’s an impressive chronological show ranging from prehistory to Cy Twombly.

The interior layout is very sober, marked by dark Oman stone floors.

It skips easily from one civilization to another.

Placed pertinently side by side there is a Brancusi, a Giacometti and a Bagua head from Guinea.

The room dedicated to Rodin and his collection of antiques is a thing of beauty.

But a space can be aesthetically lacking.

The combination of Japanese-inspired vases, bronzes by Degas and African spectacular masks makes for a disagreeable spectacle. The objects all clash with one another.

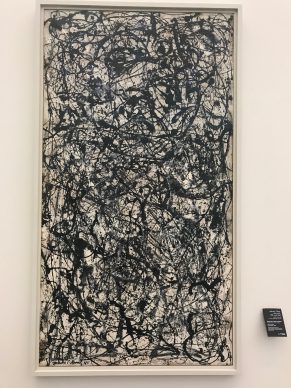

We would also have liked there to have been more space given over to the remarquable dark Rothko piece or Pollock’s magnificent drip painting, both loaned by the Centre Pompidou.

Serge Lasvignes, president of the Centre Pompidou, explains why he believes in the Louvre Abu Dhabi project.

As in all museums, at the Louvre Abu Dhabi the curators are attached to each department. The specificity here relates to the fact that they all work in pairs: French collaborating with Emirati. Thus the modern and contemporary art department is overseen by Juliette Singer, a former curator at the Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, and Alia Zaal Lootah,assistant curator who pursues her doctorate in history of art at the Sorbonne.

She explains the reasoning behind the Louvre Abu Dhabi’s choices in terms of twentieth-century art.

Lastly, among the commissions made specially for the museum and conceived at the same time as the architecture, there is a triple artwork by the Italian Giuseppe Penone with the name “Germination”. He explains his artwork.

Judging by its size, its intellectual dimension and its aesthetic proposition, the Louvre Abu Dhabi is without a doubt the most daring artistic project the world has seen for a very long time, probably since the extension of the Getty in Los Angeles in 1997.

But the Louvre Abu Dhabi is even more daring than the Getty because it is located in another part of the world, where the idea of a universal museum is utterly unfamiliar…

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.