An exhibition doesn’t need to be large for it to be sublime.

Right now, the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris is staging an exhibition of this kind. It is in this institution, the setting for what could be called the most beautiful impressionist installation in the world, the 22 panels of Claude Monet’s Waterlilies installed in a circle to create an immersive effect, that a temporary exhibition is being staged entitled “American Abstraction and the Later Monet”.

It features 29 often large-scale, unusually powerful paintings. The show, orchestrated by the museum’s director Cécile Debray, primarily stems from the fact that many American post-war artists went and drew inspiration from the illustrious Monet, the post-1914 Monet who painted right up until his final hours in 1926, his watery landscapes which have no central subject but rather a multitude of bursts of decorative effects.

Here Monet is clearly getting close to abstraction with unusually free compositions, those that were made during the great artist’s final years.

Cécile Debray about the exhibition:

But also because when these huge, powerful and ground-breaking abstract American artworks were displayed to the American public, it was necessary to justify their relevance.

What better, then, than to invoke the veteran of Impressionism to lend credibility to this new movement.

The great theorist of the abstract expressionism movement, Clement Greenberg, thus traces the lineage from the grandfather of the Waterlilies to these avant-garde movements.

He writes in 1948 of Monet that: “his practice has become the starting point for a new pictorial tendency.”

The idea caught on in intellectual circles in New York. In 1955, Moma acquired a Waterlilies panel which had remained in the artist’s studio, and Alfred Barr, the legendary director of the establishment who had already acquired a Pollock in 1950 and a Rothko in 1952, wrote: “: ‘The huge paintings, which might be called “abstract impressionist” in style, make clear why Monet has recently been so much admired by young abstract painters, particularly in America”. (in a press release from Moma: over fifty newly acquired paintings and sculptures on view at the Museum of Modern Art November 30, 1955 – February 19, 1956).

The subject could merit a gigantic exhibition that would cover all the abstraction movements from this period in the United States.

But due to lack of space for the often-monumental canvases, it means there is instead a very successful “hopping” at work.

In the antechamber to the two rooms of the Waterlilies, there is a little zoom-in on Ellsworth Kelly, who didn’t seek to copy Monet’s style so much as, in the words of Eric de Chassey a specialist on the artist and director of the Institut de l’Histoire de l’Art, “respect the idea of the purity of vision, which involves being nothing but an eye and forgetting all psychology or narration in paintings”.

Jack Shear, director of the Kelly foundation and former partner of the artist, talks about how Ellsworth Kelly discovered Monet’s work:

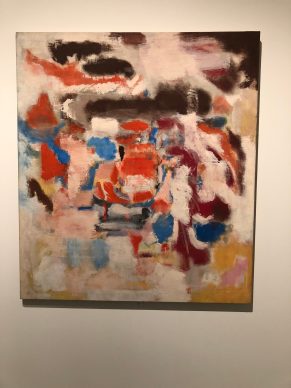

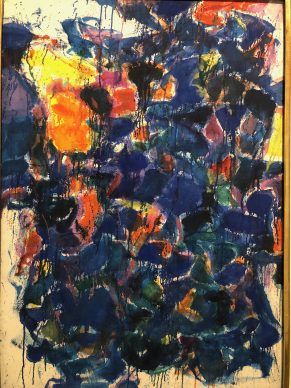

One of the most favourable associations links the master of the Waterlilies with Joan Mitchell (1926-1992), who even based herself in Vétheuil in 1969, close enough to Giverny to follow in his footsteps. Her 1980 polyptych, “The Goodbye Door”, resembles enlarged sections of the Waterlilies.

Jackson Pollock forgoes a central subject and spreads across the whole canvas in what is called an “all-over” style, like Monet.

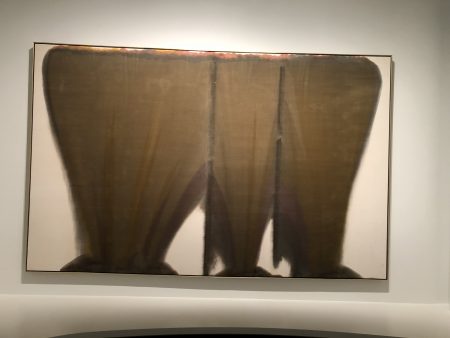

In his impressive series of “Veil paintings”, Morris Louis (1912-1962) poured paint on successive veils in watery shades.

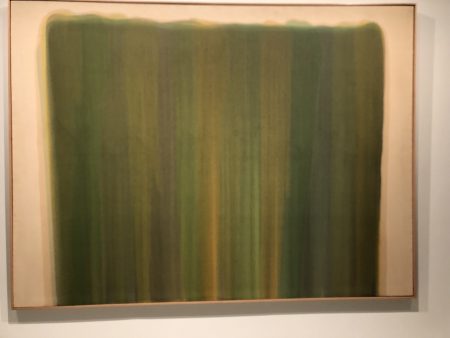

The brushstrokes of Willem de Kooning (1904-1997), who paints verdant abstractions inspired by the Hamptons, and the magnificent blurred visions of Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011) manage to approximate the spirit of the Giverny master.

And then there is Clifford Still (1904-1980), who was to become an “abstract impressionist”. Greenberg, the god of American painting theories, asserts that: “in the same way that the cubists followed on from Cézanne, Still followed on from Monet”.

There was just some difficulty in making the link between a grey and black Rothko painting and the impressionist’s verve.

The curator’s explanation: In 1964 Rothko begins work on his famous chapel in Houston, in which the immersive technique is similar to that of the Orangerie’s Waterlilies.

Pollock, Still, de Kooning and others… The richness of colours painted in large blocks or sprinkled in little daubs and splashes resembles a fervent homage in multiple variations to the beauty of gesture of the older Monet.

The exhibition would merit travelling to the United States.

Until 20 August. Musée de l’Orangerie. www.musee-orangerie.fr

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.