World afterwards again

Since the start of the coronavirus crisis there’s been too much talk about what the world’s going to look like afterwards, to the point of rendering the expression meaningless even if it’s true. No doubt mankind will still be pursuing profit and will still be just as individualistic once the global pandemic is over, but we will change just as we have changed in the past following the First and Second World Wars.

Art transformed

And we can imagine that the content of art itself, following this period of isolation enforced for humanist ends – to reduce the number of deaths – will also be transformed.

George Floyd

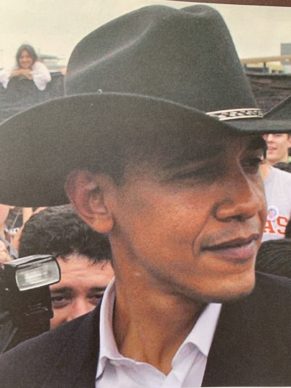

But the concurrence of events means that a post-coronavirus world is already being shaped, and it is the world that emerged after a police officer in Minneapolis murdered a citizen, George Floyd, in the street because he was black, and the scene was filmed. From that day on America has not been the same, and nor are its myths. We can no longer see the myth of the cowboy, the ultimate expression of brutal American virility, as a neutral fantasy.

Cowboy: the book

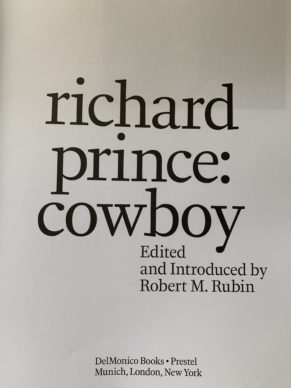

Robert Rubin is the author of a book which addresses the myth of the cowboy through the vision of the artist Richard Prince, released in March 2020. I interviewed him at the time. But I couldn’t publish the interview as it was in June 2020, in light of everything that’s happened since, without asking the author of the book another important question.

A racist America

He replied via video from the United States, filmed by his daughter

Cowboy myth

There can be no doubt that America is a victim of its own cowboy myth. But there are many ways of looking at this. In art there should be no taboos. Robert Rubin’s approach to the art of Richard Prince is both poetic and analytical.

Fantasy

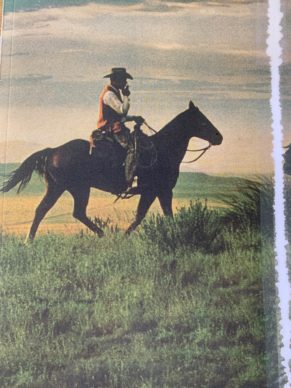

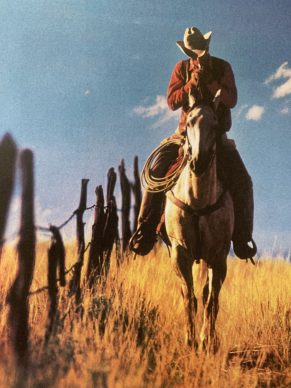

The cowboy is not so much a person as a fantasy, the figure of a sexy white man riding across the world in people’s imaginations. Wearing his characteristic hat, he’s a great shot and he lives a life of solitude on horseback. He’s an aesthete who can withstand the cold and isolation, who bathes in waterfalls and contemplates the great plains. He’s been appropriated by contemporary culture to such an extent that he’s appeared at last as a black vigilante in front of Quentin Tarantino’s camera in 2012’s “Django Unchained” and was transformed into a gay icon in Ang Lee’s “Brokeback Mountain” in 2015.

Richard Prince

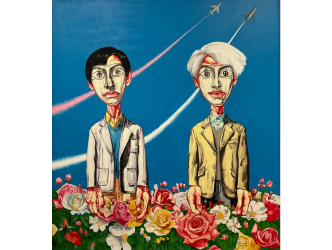

On the cowboy theme, there’s an artist who since 1980 has tirelessly explored the stereotype and world associated with this figure: Richard Prince. Like Andy Warhol, Richard Prince is one of the kings of appropriation who shares a penchant for repeatedly recycling his repertoire. His field of cowboys is now particularly vast.

Working at Time-Life

In response to a question recently put to Prince in the New York Times about the origins of the cowboy in his oeuvre, he said: “That came from working for Time-Life Publications in the tear-sheet department, where I was for several years as a day job in the ’70s and early ’80s. The job was to tear up the magazine, to give all the editorial material, which was called hard copies, to the people who wrote the editorial material. And at the end of the day what I was left with was several magazines worth of advertisements”.

Rubin & Prince

The cowboy phenomenon attracted New Yorker Robert Rubin, a specialist on modern architecture as well as Prince. In 2011 Rubin staged an extraordinary exhibition at France’s Bibliothèque Nationale with the same artist, dedicated to Prince’s passion for prints, books and other printed images, under the title “American Prayer”. This time he’s compiled a weighty 482-page book of Prince’s cowboys. This is a book as an art object, a bible of images celebrating this American dreamer, smoker, and traveller. Rubin himself appropriates scraps of text which are poetic in this context but it’s difficult to determine their authorship.

Cowboy before hippy

Robert Rubin explains the book, citing Prince: “it’s my art and your book”. He adds: “It’s not an art book, or an exhibition catalogue. Both he and I were born in a context saturated with images of the American West, especially on television. I was a cowboy before I was a hippy. It’s in our DNA. There were no revisionist westerns when we were kids.”

“This book is about him lighting out for those territories-[the] way out West. Four decades of cowboys, including Marlboro cowboys, drugstore cowboys, rodeo cowboys, urban cowboys, Hollywood cowboys, singing cowboys, lonesome cowboys.”

Robert Rubin responded to my questions from his apartment in New York, before the whole world closed its borders.