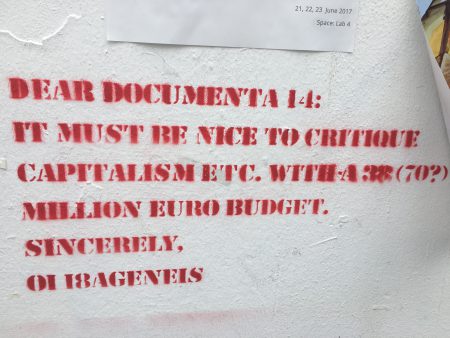

It attracts serious attention in contemporary art circles but there isn’t an awful lot of love for it.

Documenta, the legendary mega-exhibition, happens every five years in the sad, small German town of Kassel. The show has always been intellectual and political – a celebration of freedom and the post-war avant-gardes.

But for the 14th edition of Documenta its Polish artistic director Adam Szymczyk (born 1970) is mounting a revolution, flying in the face of everything we’ve come to expect.

The first change: he’s turned the event into a two-pronged show in Kassel and Athens.

It’s an elegant way of redistributing a part of the colossal 37 million euro budget (1) towards a European country plunged in a dire economic crisis. For the record, Adam also lives with a Greek artist.

Working backwards: it is also the choice of countries of participating artists, from Albania to Israel... What is at stake here is more than your standard political correctness.

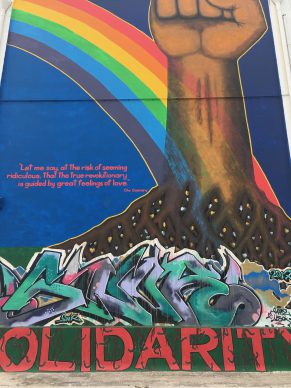

What’s more, Documenta in Athens remains unwavering in the face of the glittering art market.

The main feature of this mega-show, which for its Greek version is spread across the entire city, is its emphasis on unknown artists who are either not represented at all or are represented by small galleries.

There are a few exceptions like the Polish Piotr Uklanski (represented by Gagosian) who has collaborated with McDermott & McGough to show Hitler and Nazis’ assassinations of the regime’s ‘models’ who happened to be homosexuals, and Miriam Cahn, from Switzerland, whose sexual and political paintings have a strong presence at the international fairs via the gallery of Parisian dealer Jocelyn Wolff, among others.

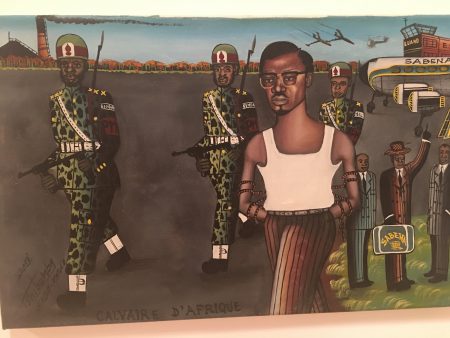

Lastly, in terms of the artists’ tools of expression, there is very little painting or sculpture, but instead videos, performances, and above all a huge number of works in the form of documents: small format photos, papers. The whole affair is awfully indigestible.

We might be inclined to label Documenta in Athens as ‘painful art’, through the category does not yet to exist.

The exhibition rooms are not designed for the visitor to while away hours reading one document after another, observing one small photo in detail after the next, and this applies everywhere, and to all the spaces.

But the power of this big show is in opening our eyes.

Never again we will be able to ignore this form of documentary art. Even if it is tedious.

The Greek version of Documenta offers a few nuggets like the 1963 film by Farough Farrokhaad, ‘The House Is Black’, about a palpably abnormal child, or the bewitching 2017 documentary by Nashashibi/ Skaer, ‘Why are you angry’, about life in Indonesia that is at once modern, decadent and flush with poetic tendencies.

But there is much more to see in Athens.

ADRIAN VILLAR ROJAS

The most spectacular show in Athens comes from the NEON Foundation, set up by the Greek businessman Dimitris Daskalopoulos.

He shunned a museum in order to finance exhibitions in public spaces instead.

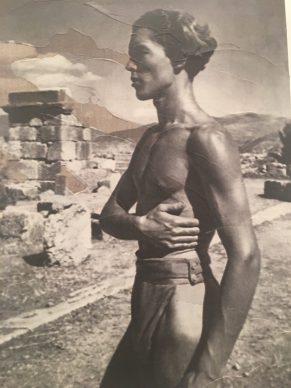

On the Hill of Nymphs, facing the Acropolis, the National Observatory of Athens founded in 1842 has been completely revisited by the prominent Adrian Villar Rojas (born 1980, he is currently exhibiting work at the Kunsthaus Bregenz in Austria and on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum in New York).

His spectacular installation ‘The Theater of Disappearance’ consists in examining the relationship between man and the land, the soil, and how this reflects identity.

In his native Argentina, he says, with its colonial heritage, the land is a wet nurse.

In Turkey, where he was showing as part of the Istanbul Biennale in 2015, he was told that the land enclosed ‘the enemy’, in other words Greece and its ancient relics.

Lastly, in Greece the soil still harbours memories of the country’s greatness: more ancient relics.

‘We were not allowed to dig down even 10cm into the soil,’ he explains.

Adrian has therefore created a sprawling project in two parts.

‘The grounds around the observatory were a desert.’ He cleaned and fertilised a portion of the land and planted 23 different plants species. We wander across on one the most historically charged places on earth, opposite the Acropolis, in a teeming Garden of Eden where pumpkins, artichokes and flowers grow wild.

On the other side of the observatory building – whose interiors Adrian has revamped in order to orient visitors’ eyes towards the Acropolis – out in the open air, he has installed vitrines that narrate mankind’s conquests, right up to Mars. Each large window, designed as a rebus, is filled with artefacts telling the story of a besieged Argentina, of man’s first steps on the moon, of the first woman known on earth, and of military landings in a hail of swords.

Elina Kountouri, the director and curator of the project, explains what she retains from this extraordinary experience.

On 24 September the observatory and the 4,500m2 surrounding it,

a national heritage hot spot,will be returned to their original state.

Beguiling beauty from a colossal act made to be ephemeral.

CY TWOMBLY AND GREEK MYTHOLOGY

There’s a little gem of a museum right in the centre of Athens, the Museum of Cycladic Art, whose director is Sandra Marinopoulou.

This summer it plays host to a fascinating exhibition about Cy Twombly and his obsession with Greek mythology.

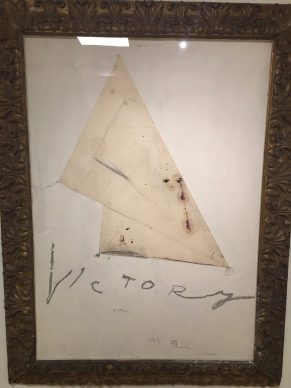

Those who saw the exceptional Twombly retrospective at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, until April of this year, and even the others, will surely have noticed the American painter’s permanent references to antiquity.

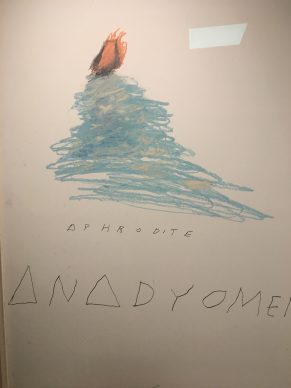

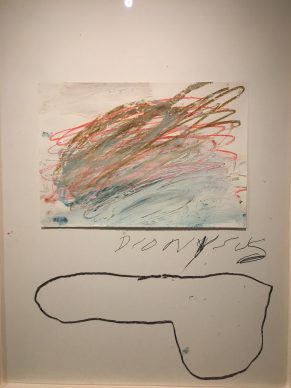

Seemingly abstruse words referencing ancient divinities are scattered throughout his canvases and drawings.

Jonas Storsve, the excellent exhibition co-curator, who also curated the Pompidou show, gives us the keys by placing his works in dialogue with ancient works.

He remarks how Twombly was probably influenced by his older sister who studied classics for six years, including Greek.

The American painter travelled to Greece for the first time in 1960 and it was in the 1970s that he made the most references to mythology.

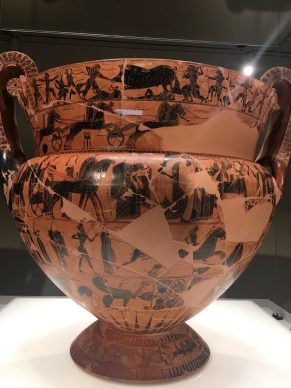

One of the most striking parallels is the monumental ‘François vase’ from Florence, painted by Kleitas, the Athenian, at the beginning of the 6th century BC, and who wrote the names under his subjects, like the contemporary painter.

There is also a Dionysus with a more than protruding phallus, which Twombly shows in large close to his name in 1975, an Aphrodite (or Venus to the Romans) in her shell and her carmine flower, and also Pan, god of wild nature, accompanied by his flute, which Twombly even represented in three dimensions in wood in 1953.

The small exhibition of 28 Twomblys and 12 archaeological objects can be compared to a cultured stroll, one designed to elucidate the mysteries of the American painter’s signs.

The miracle of an erudite antiquity resurfacing in a one of the most iconoclastic bodies of work in the second half of the 20th century.

(1) The wealth of the event, one of whose main aims is to address the poor and the oppressed, has been much discussed. So too has the budget. Here are the figures from the Documenta press office:

37 million euros divided as follows:

14 million: city of Kassel, State of Hessen.

4.5 million: German Federal Cultural Foundation

18.5 million: admission tickets, catalogues, merchandising, grants, sponsors.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.