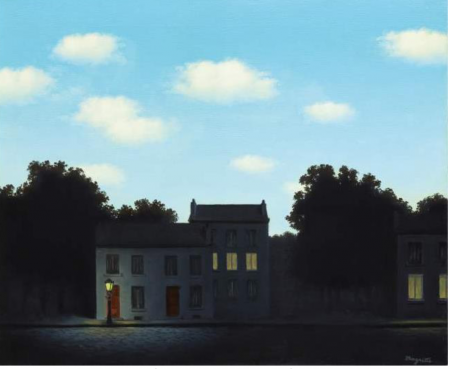

Made in 1949, it is called “L’empire des lumières” (“The Dominion of Light”).

In the painting, which is cloaked in semi-darkness, we see a block of houses lit by a few windows surrounded by trees, a street lamp illuminating the scene, but with a sky that remains as bright as day. The lower half of the painting takes place at night, while the upper half is bathed in sunshine.

Emmanuel di Donna a dealer based in New York specialized in Surrealism speaks about L’empire des Lumières. (In the video made early on I speak about 14 paintings but there are 18 L’empire des Lumières)

This painting is one of the stars of this season’s modern art sales in New York. It is estimated at 14 million dollars.

The Belgian surrealist’s record price at auction – 21 million dollars – was obtained for “La corde sensible” (“Heartstring”), a canvas dating from 1960 depicting a glass filled with clouds set in a mountain landscape.

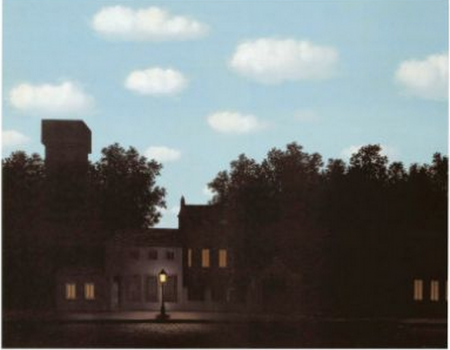

But the second-highest price was obtained for another version of “L’empire des lumières” dating from 1952, which set a new record in 2002 at the time: 13.7 million euros. According to Artprice, since 1992 there have been no less than nine “reproductions” of “L’empire des lumières” that have gone to auction.

What can be the explanation for this?

An explanation is offered by the president of the Magritte Foundation, Charly Herscovici, who accounts for 18 paintings christened “L’empire des lumières” within the artist’s body of work, up until his very last canvas made in 1967 mere hours before his death, which remains incomplete. Not to mention the gouache pieces on the same theme, of which there are ten.

According to Charly Herscovici, we might even say that it is the most repeated of all the artist’s artworks. “In terms of recognition, this subject is on a par with Warhol’s Marilyn.”

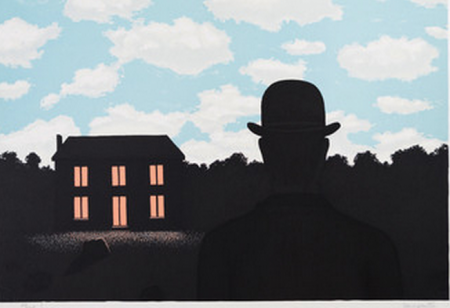

The president of the Magritte Foundation provides an explanation for the repetition of the subject. (Note that he speaks from memory about 14 versions of “L’empire des lumières” before the different versions have even been verified. Christie’s makes reference to 17 versions since clearly the auction house does not count a version which features a figure in a bowler hat in front of the houses.)

Since the 1920s, Magritte had the desire to express a certain sense of strangeness in his paintings.

He was not always the famous painter as he is known today.

Before and during the war, the most remunerative aspect of his work was for the least chaotic.

But in 1947 he met Alexander Iolas, who was to become his New York art dealer. It was from this moment on that the Belgian artist found financial success.

“Iolas had a good sense for which pieces worked,” explains Charly Herscovici.

Magritte would himself state that “It is useless to send paintings to America that are all completely new. By all means, send some, for there is a slim chance that they will find buyers. But above all, you’ll need replicas of paintings that are already well known and palatable.” (1)

But Charly Herscovici considers Magritte to be a painter who is not money-obsessed.

The author of the artist’s catalogue raisonné, the late British art critic David Sylvester, recounts the antics that ensued between the Belgian artist and the American art dealer.

The latter would request certain subjects and the artist would end up executing them. “Of course, he doesn’t take much pleasure in painting the repetitions, nor is he very motivated, but yes, the variants do include certain versions of ‘L’empire des lumières’.

Magritte made many of them with the sense that each one could be better than the last.”

And once these repetitions were paid for, Magritte amused himself by claiming to the tax authorities that this source of revenue came from the reproduction rights.

Peak production for “L’empire des lumières” came in 1954, when he painted four versions of the painting plus a watercolour. This latter piece belongs to the French media figure and great collector of surrealist art Daniel Filipacchi.

Magritte’s artist peers frowned upon this kind of repetitive activity. Thus Marcel Duchamp, when asked to contribute an introduction for a catalogue, wrote simply playing with words: “Des Magrittes en cher, en hausse, en noir et en couleurs.” (“Pieces by Magritte in expensive, in more expensive, in black and in colour.”)

Nonetheless, this proliferation has had a positive effect on today’s market by increasing the desire for possession among collectors.

The specimen sold by Christie’s is a small format piece that first belonged to Nelson A. Rockefeller, who immediately gifted it to his secretary, for whom he seemed to harbour a particular affection. From a professional source, the painting would this time be put up for sale by a bank that had acquired it with a credit guarantee.

Today, the other versions of “L’empire des lumières” can be found at the Magritte Museum in Brussels, at Moma in New York, in the private collection of the Samsung family in Korea, or in the famous Basel collection of Esther Grether.

“The valuation seems relatively reasonable when you take into account the significance of this painting. The market doesn’t like valuations that are too extreme. That’s why the Francis Bacon painting valued at 60 million pounds, one of the Pope portraits, recently failed to find a buyer at Christie’s in London,” Charly Herscovici comments.

The fact remains that the Rockefeller version of “L’empire des lumières” has been circulating a lot recently, offered in vain in the context of private transactions, before landing under the hammer at Christie’s.

This 1949 painting alone encapsulates a plethora of the current art market’s virtues and vices.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=61ZaCUutHnQ

- (1) Magritte Catalogue from Jeu de Paume. 1999. Editions Ludion.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.