Obviously, the opening of the Venice Biennale is the only place on earth where, within a few minutes, you can meet the Danish artist Olafur Eliasson and the Italian Maurizio Cattelan, the Indian billionaire Lakshmi Mittal or the priestess of fashion, Miucca Prada. There’s nothing comparably attractive in the world in terms of contemporary art.

Of course, the Venice Biennale is first and foremost a contemporary art orgy: some 178 artists in the international pavilion; 88 artists representing 88 countries; as well exhibitions scattered throughout the city.

There’s too much to tell and, of course, you miss a lot of things. I’d be curious to know who went to the Palazzo Cini before the results were announced, who visited the Angola pavilion, which won the Golden Lion? Not me anyway. I left too early. Too bad.

I spent a long time, however, looking at the work of the artist who got the Golden Lion: I am referring to Tino Sehgal, the new king of a new kind of performance. Sehgal issues rules of actions that are meant to take place in one given place, but he demands that no trace be left after he sells his work. No photo, no contract, no check. I wonder if he accepts cash only. But let’s not make fun of this: his work is fascinating. In Venice, as a reflection on the 20th century, Sehgal wanted to present actors who were singing and dancing while kneeling: according to him, a sign of humility and gratitude. I remember, at a previous Biennale, his speech in the German pavilion, more explicit and more brilliant. Actors exclaimed, among other things: “This is so contemporary!” Derision. And then, his idea of banning pictures makes me think of the ban on taking photos in museums. Unrealistic and authoritarian. Incognito among the crowd, the artist makes sure the operation unfolds as planned.

Take a look, as if you had been there:

I have not filmed Camille Henrot’s remarkable video but I took pictures of it. She is the happy recipient of the Silver Lion. A work scanned to music that resembles rap’s ancestor, with a text she wrote which resembles liturgical poetry. Like the story of the animals leaving Noah’s Ark, with matching accumulated images and with some surprising breaks in the enumeration. Very talented. Henrot narrates the thing with enthusiasm and sensitivity.

On the other hand, in the Chilean pavilion occupied by Alfredo Jaar, I happened upon the moment when the tank, filled with dirty water, begins to shift to reveal a Venice that had disappeared under the water. The city’s fatal future is taking shape, but it’s a happy ending since it resurfaces every 3 minutes for a few moments in the shape of a reconstituted Giardini.

On the fly, I also took in the strange scene of a Viking ship filled with musicians playing in full uniform. This is Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson’s fantasy come true.

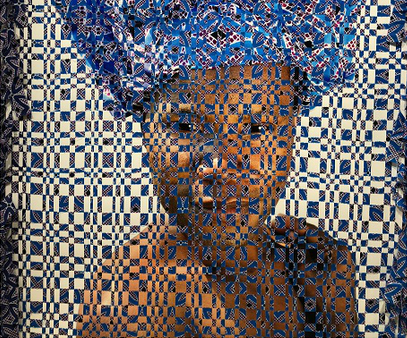

Some time ago, I wrote about the particularly successful exhibition at the Pinault Foundation’s Palazzo Grassi imagined by artist Rudolf Stingel. It was a demonstration of how very erroneous the opinion we form about an artist through a few works shown in galleries can be. I had seen a few boring abstractions. The exhibition, however, is a work about the vacuum, the taking over of a palace by a recurring Orientalist-like motif, a reference to the Venetian past, but also a work that is referenced in the same manner as Goethe’s poetry is. Soak in the atmosphere. This is 21st-century Germanic Romanticism done by an Italian living on the border.

At the Punta della Dogana, the other of Pinault’s Venice locations, is an exhibition of selected works from the foundation’s collection. The nicest thing about Pinault is that this son of modest Brittany stock turned billionaire dares to thumb his nose at received ideas. Curated by Michael Govan, head of Los Angeles’s LACMA, and by Caroline Bourgeois, a curator at the foundation foundation, the exhibition opens with an installation by Lizzie Fitch and Ryan Trecartin. (See my dispatch of a few months ago about their exhibition at Paris Musée d’Art Moderne). The first room looks like a custom-kitchen and garden-furniture showroom. Both artists deal with the American middle class, the dumb teenage years and the dreams stirred up by television.

Two strong strands run through the exhibition. One stems from a desire to strip things down and a taste for the conceptual and sober. Kitschier and more expressionist, the second underlines its own effects.

The Prada Foundation is innovating with the recreation of a landmark exhibition, Harald Szeemann’s “When Attitude Becomes Form,” CHECK which took place in Berne in 1969. In collaboration with artist Thomas Demand and concept-loving architect Rem Koolhaas, curator Germano Celant has come up with a redo. The result is more interesting intellectually than visually. This is an exhibition whose essence is conceptual. An exhibition that verges on performance. This exhibition is the exact transcript of the 1969 Kunsthalle show in a restored Venetian palace in 2013. Ellipses appear where works are missing. The always fascinating Celant, who knows all there is to know about the great decades of the ’70s and ’80s, recalls how the idea for this exhibition came about. “I was talking with Miucca [Prada]. We’d just done an exhibition about art multiples/edition CHECK,” he recalls. “She said: ‘In the end, the only thing that hasn’t been reproduced is an exhibition.’ The most delicate issue was that of the missing works, and since these were predominantly traces of spontaneous artists’ gestures, the temptation was great—despite (according to him) Celant’s protestations—to create their likenesses. And so, hoping to end the discussion and avoid the creation of replicas that weren’t true to the gesture, Thomas Demand said, “So we will call the exhibition ‘When Attitudes Become Fakes.’” The catalog is a memorable record of the Prada Foundation’s initiative, which, unfortunately, costs 90 euros.

Side trip to the Scuola San Rocco. Here, attitudes have taken sacred forms. Sacred or sublime. They leave you breathless.

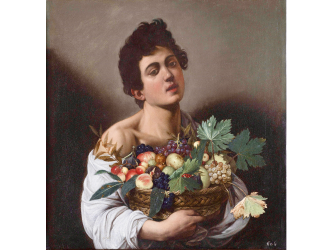

Another side trip to the Manet exhibition at Palazzo Ducale. The face-off between his Olympia and Titian’s Venus of Urbino holds up. Simply, each of them tells a story. On one side is a lady selling her charms, on the other is a beauty offering herself to her husband. It’s a powerful aesthetic emotion.

Back by plane. The skies were sublime too.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.