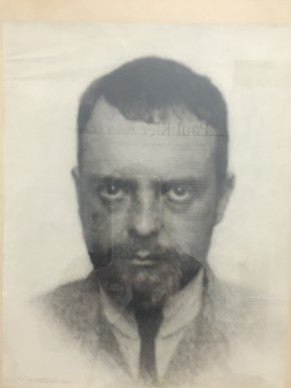

It’s the most eagerly anticipated exhibition this season in Paris. 230 works dedicated to an unclassifiable, singular and exceptional artist, and a major figure in German modern art: Paul Klee.

The show’s curator Angela Lampe has pulled off a small miracle, creating a narrative that is at once lucid and complex. She brings into focus the successive phases of an artist who flirted with different key movements like cubism, orphism, Dada, surrealism and Bauhaus, though squaring them with his private obsessions. By the end of the exhibition, its aim becomes clear. Klee was an artist who evolved a highly personal vocabulary, perhaps even a pictorial alphabet. It’s a detached, multilayered, and not always explicit universe, but at the very least we’re able to grasp the logic of its chronology.

His first steps on the path towards a different kind of art began in 1914 on a trip to Tunisia. His exposure to the North African light, mixed with his discovery of Picasso’s cubism and Robert Delaunay’s colour theories, give rise to canvases of polychrome squares. These are decompositions of forms where, through the contrast of colours, life explodes.

Klee spent some of the war in an aviation school and the presence of those huge flying machines led him to imagine hybrid beings, the offspring of man and machine, which would impress the surrealists. The celebrated philosopher Walter Benjamin owned the drawing called Angelus Novus (1920) about which he wrote: ‘This is how the angel of history must look.’ It is a mechanical angel whose head is turned toward the past and whose wings are beaten back by progress. Benjamin developed multiple interpretations around the painting that illustrate the complexity in reading Klee’s work. Angelus Novus has been loaned for this exhibition by the Israel Museum. Due to the fragility of this work on paper, it can only be exhibited two and a half months every year, and this year’s entire allocation has been reserved for visitors to the Pompidou Centre.

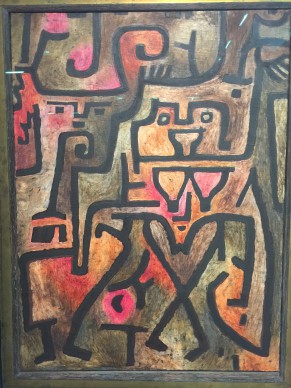

The artist from Germany whose art would be categorised as ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis went into exile in Bern, Switzerland from 1933. He was fascinated by ancient cultures such as that of Egypt, and cave art. But unlike other artists, he never attempted to really appropriate these historical genres. Instead he made simulacra of them. One of the most stunning compositions in the show, presaging the minimal art of Sol Lewitt, is an aquarelle from 1932 called Pyramid comprised of simple geometric forms.

Klee is a witty figure. His compositions are permeated with black signs on coloured backgrounds that are parodies of kinds of hieroglyphs. In Insula Dulcamara (1938), the largest canvas he ever completed, 176cm in length, one envisions Arabic letters but also possibly a face with a Hitler moustache.

Klee was struck down by scleroderma, a serious illness that shrank the skin on his body and restricted him to making small, delicate compositions that he was very fond of. He died in 1940.

From 6 april to 1st August. www.centrepompidou.fr

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.