The meaning of the work

“The meaning is what you bring to the work.” When I interviewed Richard Serra (born in 1938) in 2008 about his monumental installation at the Grand Palais in Paris called “Promenade”, composed of five steel slabs each measuring 17 metres tall, standing like cathedrals reaching towards the heavens, the American star artist uttered this truth.

Georges Seurat

No figuration

He also stated his total rejection of figuration: “I’m not interested in figuration. It’s false. The narration doesn’t interest me. It’s made in a material to make you think it’s a reality and it doesn’t.” At the time, mobile phones weren’t able to film but I recorded the conversation, an extract of which is here. Naturally the references evoked by Richard Serra which served as a basis for his creations are works of architecture, such as the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul or Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp chapel in France.

Richard Serra

Georges Seurat

Around the same time I took Richard Serra, along with his wife Clara, to visit a remarkable private Parisian collection of drawings by Georges Seurat. They were of course figurative. You can imagine my surprise to see the artist in a state of ecstasy , to the point of saying that he wanted to achieve something similar to what he saw in these works on paper.

Georges Seurat

I love paradox

The most interesting phenomena are always related to paradox. Fast-forward several years to 2022, and I am co-curating an exhibition at the Guggenheim Bilbao taking place until 6 September, which establishes this dialogue that emerged from the mouth of Richard Serra one day in spring 2008 at the Palais Royal gardens in Paris.

Georges Seurat (detail)

Rambles

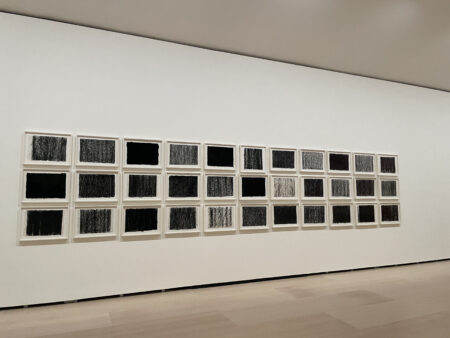

Richard Serra not only agreed to the idea for the exhibition, loaning 81 of his drawings from the Rambles series produced around 2015, he was also willing to part with one of the Seurat drawings from his personal collection.

The Matter of Time

Alongside his Ramble drawings, the Guggenheim Bilbao – which also possesses the extraordinary permanent installation “The Matter of Time” – is exhibiting 22 drawings by Seurat produced between 1880 and his sudden death in March 1891 at the age of 31.

Exceptional power

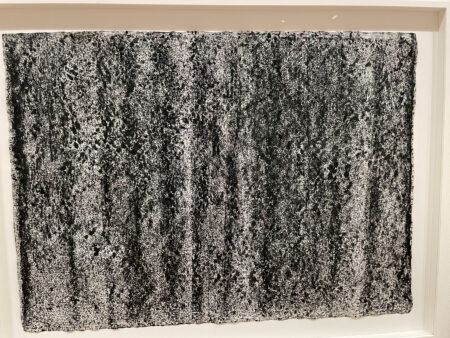

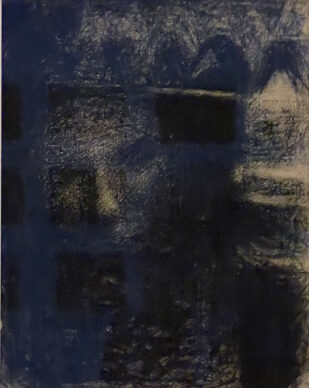

The first thing to comment on is the exceptional subtle power that emerges from daily visits (for the whole period of installing the exhibition) to see the neo-impressionist’s drawings. Daniel Buren talks, in a very enlightened way, about the principle of pixelation having been invented before the computer, by Seurat. The marks he makes are like a “dripping” technique using crayon, scattered across the sheet of paper.

Georges Seurat ( former collection of Henri Matisse

Particular style of drawings

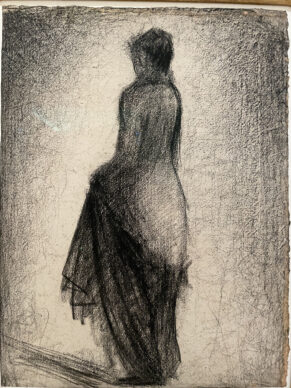

Georges Seurat, in parallel to his theories of the divisionism of colour in painting which would give him the label, invented by the art critic Félix Fénéon in 1886, of “neo-impressionnism”, developed a particular style of drawing which would elevate him to the pinnacle of art history in this area.

Georges Seurat (detail)

The magic formula

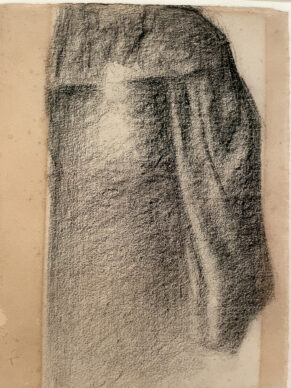

The “formula” that he invented over the course of two years of diligent practice after leaving military service in 1880 was always the same: take some paper with a thick and irregular texture -Michallet paper- and work intensively using Conté crayon to create volume and shadows by emphasizing, or not, the black. In 1882 and 1883 Seurat dedicated himself almost exclusively to producing drawings.

Richard Serra

Rembrandt, Goya, Daumier

He referred to many works on paper, including etchings by Rembrandt, Goya and Daumier. His drawings were an expression in their own right, but they also served as preparatory studies for his paintings. In total, over the course of his very short career before his death from diphtheria in 3 days at the age of 31, he produced 527 drawings.

Major influence

Georges Seurat, Former collection of Pablo Picasso

The exhibition that I am curating jointly with Lucia Agirre curator at the Guggenheim Bilbao, also aims to show how Seurat would have a major influence, through his drawings, on what came next in art history. Artists who were his contemporaries, and the subsequent generations, would not only look at Seurat’s drawings, they also wanted to own them.

Pissarro, Signac, Picasso, Matisse

Georges Seurat

Starting with Pissaro, the impressionist who had a period up until 1890 when he embraced the neo-impressionist thesis. The venerable master acquired seven drawings by Seurat. Signac, who also embraced the divisionist theories of his friend Seurat, owned no less than 70 drawings by Seurat which accompanied him in his everyday life. Two giants of 20th-century painting, Picasso and Matisse, both had collections of Seurat drawings, seven for the former and four for the latter.

Henry Moore, Jasper Johns

Georges Seurat. Collection of Henry Moore

The surrealists were fanatical about his mysterious works on paper, located in an indefinable time, between day and night, and in which the human shadows play a role that’s almost as important as the figures themselves. We could also mention Henry Moore who acquired three drawings by Seurat, one of which is exhibited in Bilbao, Jasper Johns, who loaned us an extraordinary “Torse de femme”, and of course Richard Serra with his “Fauteuil”, marked by a shadow and its equally dark double.

Confusing impression

Richard Serra

Placing Serra and Seurat in close proximity creates a confusing impression, as though Serra, through his abstract series which play with the texture of lithographic ink, has magnified certain details in Seurat’s compositions.

In these series which function as a single artwork, featuring variations of tonalities from grey to black, a gestural quality may be perceived that the two artists have in common, creating volume, density, lightness, and textural effects.

You give to the work

As Richard Serra might conclude, “meaning is what you give to the work.”

Georges Seurat (collection of Richard Serra)

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.