Breathtaking show

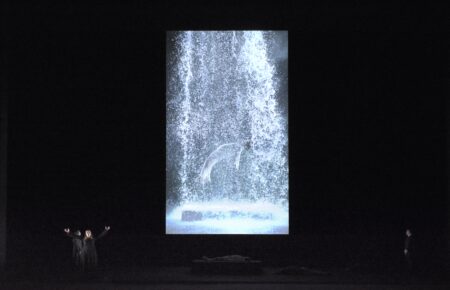

For the sixth time, Paris’s opera house is staging Wagner’s great opera, Tristan and Isolde, accompanied by images from Bill Viola (born in 1951) and directed by the American theatre director Peter Sellars. The show is breathtaking and the five hours spent in the room (including two intervals) go by with ease because it all takes place within a kind of augmented reality.

Two parallel visions

There is the action onstage and also the action behind it on a screen measuring 11.7 x 6.7 metres. These serve as two parallel visions that mirror each other, intertwining the lives of the two heroes, who themselves are presented almost permanently as a pair. The interesting thing about this work, which was developed in 2005, is the fact that, as Peter Sellars explains here, the images created by the pioneering video artist Bill Viola were conceived to reflect not the music, but the text. It is all the more interesting since the video is not a literal illustration of the narrative.

Impossible love

The opera deals with the theme of impossible love but also, as Sellars points out, with a melody without end linked to the idea of Karma, which Wagner learned about at the time – we note in one of the songs the following words: “my father begot me and died; my mother gave me birth and died, to what fate was I destined when I was born?”

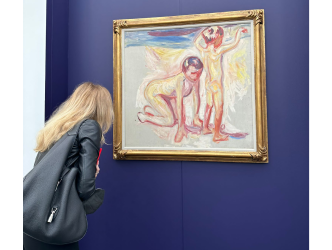

The most significant work of Bill Viola

Paradoxically, Tristan and Isolde has also become the most significant work by the American visual artist and is uniquely visible today, not in a museum, but accompanied by an orchestra of a hundred musicians. Here we encounter Viola’s obsessions set against a musical backdrop: the metaphysical dimension of life and the fundamental presence of water.

Seurat drawings in an animated version

One of the most striking sections, in black and white, consists of a human form that emerges from the darkness again and again. It’s made up of a pixelated texture that resembles the drawings characteristic of the post-impressionist Georges Seurat, only in an animated version.

Based on the visual aspect, we primarily retain from this staging that it is literally and symbolically an immense work about time.

You were born in Pittsburgh like Andy Warhol?

Yes, I was born in Pittsburgh like Andy Warhol, Martha Graham and Gertrude Stein.

But they all escaped from Pittsburgh.

Yes. When I went to New York, Andy was already Andy. And one of the projects I worked on with Andy was the Andy Warhol robot. I had to direct a show in which he was a robot. Andy wanted his robot to participate in the late-night TV shows so he wouldn’t have to. One of the last things we did while he was still alive: we measured him. We had a complete replica of Andy with animatronics from the 80s. But, of course, when he died the foundation cancelled everything.

It’s interesting because some persons are now criticizing Yayoi Kusama’s collaboration with the Vuitton brand where she’s depicted as a robot in their store windows. When I saw that I thought that if Andy was alive he would have loved to do it.

He would have a good time. It’s the same principle. It’s about dehumanization and humanizing everything. It’s about celebrity, being present everywhere. Andy realized the only thing that matters is when people are thinking about you. That is worth money. The only international currency is celebrity.

Are you sensitive to that question: celebrity?

No, because only people who know what I do know who I am. And that’s fine. I can be a real person in the street.

You have given your archive to the Getty. That’s a form of celebrity.

Oh no, the Getty have a lot of archives of obscure artists. A lot of my projects in LA are connected with the Getty. The Getty has been quite visionary in supporting a lot of my works. So I wanted to thank them.

What does it represent to give your archive to the Getty?

I’m not somebody who looks back, so it’s a relief. For me theater is the art of the moment and the art of the next moment. I don’t have time to look back. I have so much incoming every day. It’s great to have that out of my life in order to be able to look to the present.

But theater is also the art of the past, right?

But it’s channeling art of the past in a very deep way. Wagner in Tristan and Isolde discovered Karma. He was reading Buddhist texts, which were starting to become available in Germany in the 19th century. And of course when we look at them now they are incomprehensible. Now we have the Dalai Lama as a friend and neighbour. But back then nobody knew what Buddhism was. But the big shock is that Wagner understands Karma. Modern science is now confirming it: every cell of your body is the trauma of your mother, the trauma of your grandparents, all of this is remembered…

Is that what you are showing in Paris?

Wagner was the first in the history of western music to create, with Tristan and Isolde, the endless melody. A melody which goes across generations, across centuries, across civilizations, and this is why Tristan never stops. Everything before this was numbers: a chorus, an aria… Suddenly Wagner was the first: everything is woven together, and it never stops because it’s about eternity. Something that moves from your ancestors and is in your body right now and you hand on to the future.

Bill Viola and Kira, his wife, were living in Japan in the seventies when Sony was inventing each new step of video. They were working at Sony and they had a Zen master teaching them. And everything Wagner was trying to guess, Bill actually understood.

What was the genesis of this project with Viola?

Bill and Kira were the reason I wanted to move to California and they were the first people I met there. I thought: anywhere there is an artist doing this kind of work I want to live there. This was 1987. We were friends right away. My first night there we had dinner together and we spent a lot of time together over the years. I was always inviting Bill to work in theater and he was saying: No. Theater is shabby, it’s a mess. On the other side he invited me to work in museums. So when we did his 25 year retrospective, which toured 5 museums, from Whitney Museum to the Stedelijk in Amsterdam, we worked very closely on the catalogue, on the exhibitions.

And?

Wagner invented the total work of art: the Gesamtkunstwerk. Poetry, dance, visual art. All these things meeting as equals. I needed for Wagner an artist who could look at him eye to eye and not serve Wagner but be in dialogue.

Bill and I talked about Tristan and I gave him a lot of books, we spoke about a lot of specific things and then he shut the door for two years and came back with 5 hours of videos in 2004. We did not speak at all for two years. You know Bill goes deep inside himself.

What was Bill Viola’s relation to the music of Wagner?

Bill really chose not to be inebriated by the music. He kept the music out of his system. He only responded to Wagner’s text. He never created a soundtrack. He needed his images to have the same power as the music. That meant he could not listen to the music.

And when he opened the door?

There were 5 hours of incredible videos. It’s such an outstanding gift. I’ve seen it for 18 years now. I know these videos extremely well.

What was your reaction?

I accepted them instantly and started to do something in dialogue with them. And now that I know them very well, what I’m doing on stage is even more intricate in terms of the dialogue. I have a very big responsibility because it is the largest and, in a way, most powerful lifework of Bill Viola. It’s a piece that can only be seen in a building which can hire an orchestra of a hundred, choirs of 50. You can’t see it in a museum. He paid for this by making small editions of a few of the images that are in museums and the homes of private collectors. Because no theater could ever commission five hours of Bill Viola. It was a huge shoot, some big Hollywood shoot with airplane hangars, a giant cruise, walls of fire, all these very dramatic things and also something he made with the hand-held camera standing by the sea. Bill takes you to this immense cosmic place.

You are putting on the show for the sixth time since 2005. Have you changed things in terms of staging?

Of course, every day. This is very different from the former versions. One of the most important things is the casting. Half of the singers are people of color. So you have a black Isolde, and it’s another story. Suddenly we are in this whole other dimension. Plus the whole of society is different. In the past 3 years everything has changed.

What has really changed?

Now we can feel the intensity of the anger, the intensity of the rage. We are living in a society with a huge amount of rage. How do you move through that to some kind of reconciliation and understanding? We are also living in a period of a suicide epidemic. Tristan and Isolde are going to kill themselves in the first act.

Did you radically change the mise en scène?

For me what’s interesting is that we respond differently to the same image in a way we did not experience it before. We spent most of the rehearsal crying our eyes out. We were liberating, dealing with intense issues.

Musical direction: Gustavo Dudamel

Until 4 February. https://www.operadeparis.fr/en/season-22-23/opera/tristan-und-isolde

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.