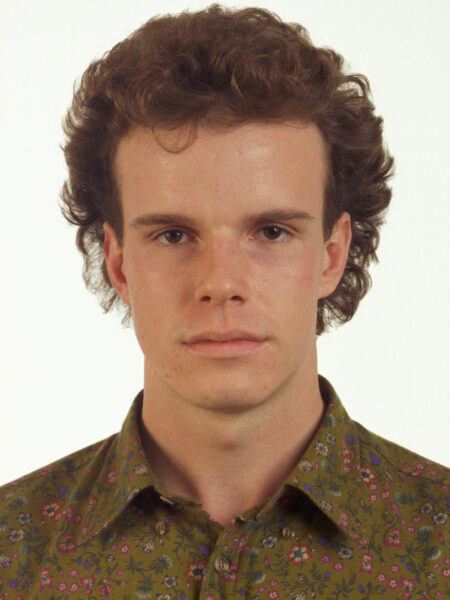

1968

The story begins in 1968. The year that was defined by a generation who, across the world, proclaimed their desire for freedom. 1968 was also the year that marked the death of the French turned American artist, Marcel Duchamp. The youngest and most innovative of the older artists of the 20th century took his final breath in his apartment in the bourgeois area of Neuilly at the age of 81. That year also marked the birth of someone who would very quickly become exceptional, with the ability to be everywhere at once, a person who is passionate about art, always seeking novelties with a sense of urgency, a man who seems to never sleep and has little regard for his own personal comfort, a champion of artists across genres: Hans Ulrich Obrist (HUO).

During lockdown

Thomas Ruff

“May 68 is my date of birth. And I like this little nod to history.” This is how his book of confessions begins. During lockdown, the director of the Serpentine Gallery wrote a book in French which reveals a bit about his private life. The most exciting part details his childhood in German-speaking Switzerland in a town on the border of Germany and Austria. But don’t expect big, shameless confessions telling us all about his romantic conquests, his sexuality or the people he dislikes.

Traffic accident

Hans recounts his unquenchable thirst for knowledge in art, his isolation as a child who was different, the support of his parents and a founding event comparable to all those experienced by creatives kept confined to their beds for long periods of their childhood – from Marcel Proust to Paul Eluard. For HUO it was a traffic accident at the age of 6 that would definitively change the course of his life. “A car that was driving too fast hit me while I was crossing the road on the way to school.”

Generosity

On page 91 he writes what could be seen as a kind of confession-conclusion: “I have always thought that my medium was generosity.” I wanted to complement the book written in French by asking him a few questions via video link in English. As usual, HUO took to the game well.

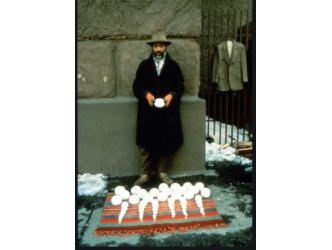

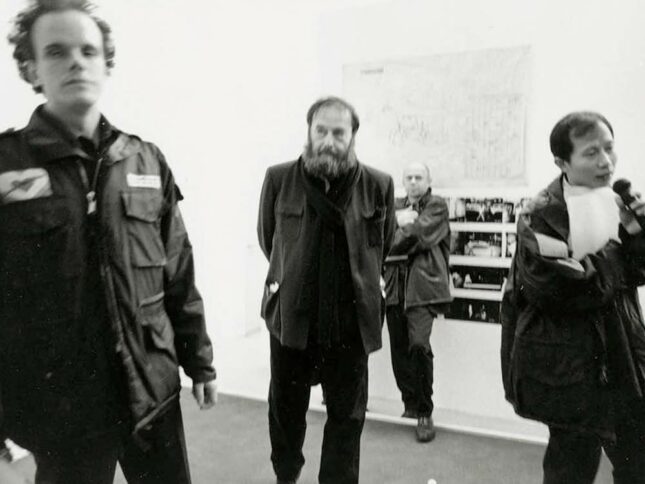

Armin Linke

Une vie in progress. Seuil/ Fiction et Cie. 21 euros.

The centre of my life

I thought that day was my last. It created in me the need to truly accomplish things. Very quickly, books became the centre of my life, a desire for knowledge. I discovered art through postcards. So I created a sort of imaginary museum.

Loneliness

Growing up in a small town in Switzerland meant that people did not necessarily have the same kind of interests as me. This created in me the desire for connections. Really early on, I started to reach out with an urge to connect.

Museum

My parents never took me to an art museum. The only museum they took me to was the magnificent library at a monastery in St Gallen.

Mother

My mother was a schoolteacher and she was very interested in a non-authoritarian education. I was always interested in art but quickly I realized that for her, making art was an unrealized project. I was not calling her everyday but instead I was always sending postcards, like Serge Daney. I was also sending my parents a lot of art books. My father did not really read but my mother started reading everything. She did that for many, many years as I began sending books when I was a teenager. She passed away two years ago. That means that over about 35 years she got many, many books from me. And something very mysterious happened, because toward the end of her life she started to make art, art objects and small installations in the apartment, which were almost invisible.

Iwan Wirth

As a kid, around the age of 15, I often went to the Erker gallery in St Gallen. Basically, there was a person there who told me: “there is this teenager who’s even younger than you who also comes every month and buys books. We have to arrange for these two teenagers to meet”. We started talking about what we’d seen. His name was Iwan Wirth( See here an interview of Iwan Wirth). In Switzerland there was a dense scene of art activity. In almost every town you had a Kunsthalle or a museum.

Fischli & Weiss

That was a life-changing experience. I was 17 and I went to the studio of Peter Fischli and David Weiss. It was a day when they were working on this extraordinary film: “The Way Things Go”, which is basically a chain reaction. Seeing this extraordinary studio, I thought: that is what I want to do, to work with artists. To find a way to be useful. They were incredibly generous. In a way, you could say that the day I visited their studio also triggered a chain reaction in my life. From then on it just never really stopped.

The realized “unrealized project”

After meeting Fischli & Weiss I began taking night trains all over Europe. I had no money. I could sleep on the train and I could travel for one month using Inter rail tickets and make studio visits. As I was so young, artists gave me tasks. I visited Rosemarie Trockel in Cologne. She advised me to visit forgotten pioneers, especially women artists. So in Vienna I met Maria Lassnig.

Fischli & Weiss gave me the idea to visit Boetti. I went to Rome. I spent a day with him. We went to see the astrologer Mariangela, who was also the astrologer of Fellini, one of the greatest astrologers I have ever met. It was a great day and at the end he said: “I will give you a piece of advice: you ought to always ask artists about their unrealized projects”. It was 85-86.

Boltanski’s advice

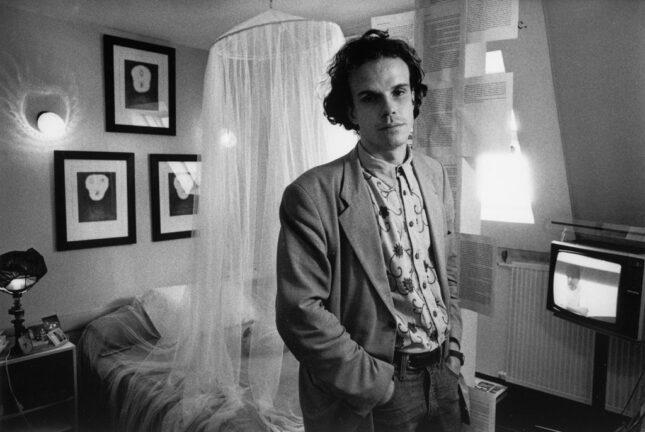

Christian Boltanski

In Paris I decided to ring up Christian Boltanski and Annette Messager and we spent an afternoon together (See here a report about Boltanski and here about Messager). I visited both of their studios. Boltanski told me: you don’t have to wait until someone offers you a museum. You could just do it. He also told me: you could come up with new rules of the game for the exhibitions. We spoke about unexpected places to stage an exhibition. In a very modest hotel in Montparnasse in Paris I organized an exhibition with 70 artists.

Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter

Around ’86, a Gerhard Richter show came to Berne. I went to the opening and spoke with him. He invited me to Cologne. He told me that he often went on holidays to Sils-Maria. It’s a magical place in the Swiss mountains where Scandinavia and the Mediterranean meet. We visited the Nietzsche house together, where he wrote Zarathustra. I suggested to Richter to exhibit his little photos of mountains with abstract lines of colour on top. It would become my first exhibition in a house (See here a report about a Richter show).

Negative feelings

When I grew up in Switzerland there was a museum director who talked a lot about the artists he did not like. It had such a negative impact. It closed a lot of doors. I was a teenager and I told myself: I’m never going to do that. I try to work to produce a positive reality.

Astrology

Mariangela was absolutely amazing. But she did not do it as a profession. She did it for friends. And when she passed away it was difficult. Now there is a new generation of astrologers.

Future

As Marta Rosler once said: “Future flies in under the radar”. In the near future I am very excited about the opening at the Serpentine of the pavilion by Lina Ghotmeh who is an extraordinary Lebanese architect based in Paris (See here an interview of Lina Ghotmeh).

For the future of art,

I think video games are a very interesting new art form.

Another pattern I sense very strongly right now when I visit studios and when I see artists is that there is a kind of desire to once again connect over a longer duration, to go beyond event culture. Event culture is not sustainable. They are thinking about more sustainable formats. For example, for Precious Okoyomon the interest is more in gardens than in exhibitions. The exhibition becomes a garden with a sense of slowness, another temporality. The artist Alexandra Daisy Ginsburgh imagined a garden for pollinators. Yinka Shonibare just opened a residency in Nigeria but also a farm, 2 or 3 hours outside of Lagos. Otobong Nkanga spoke to me about an idea of a farm for artists. It’s the role of the institution to take that into account. Things have to be longer now. What does that mean? Maybe exhibitions need to be longer also. Longer exhibitions in new formats, maybe gardens, maybe farms.

Love

Love is the most essential thing, and the person who said it beautifully is our friend Etel Adnan when she said that the world needs togetherness. Not separation, love. Not suspicion, love. Not isolation. Like a mantra: in the practice, in the work, in everything. I always take this sentence with me. It accompanies me wherever I go. (See here and here a report about Etel Adnan).

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.