There is not one surrealism, but in fact many surrealisms.

Proof if required is to be found at the Centre Pompidou where that most Belgian of surrealists, the painter René Magritte, is in the spotlight until 23rd January.

Also at the Pompidou until 17th January is another completely overlooked piece of that avant-garde movement.

The unmissable show reveals how Cairo, a far cry from the face that the Egyptian capital presents to the world today, was animated by a group of wild, pertinent and politically engaged artists.

The show consists of 130 paintings sourced from 15 countries.

It is the first museum exhibition to tackle the subject of Egyptian surrealism, and has been put together by Sam Bardaouil, who wrote a dissertation on Egyptian surrealism, in association with the independent curator, Till Fellrath.

Here they talk about the idea behind the exhibition:

In the 1930s, the Egyptian capital, still under British rule, was a cosmopolitan, rebellious and outward-looking city where French was the lingua franca.

It was in this context that in 1938 a group of intellectuals, who were often as comfortable writing as they were painting, created Art and Liberty, a group which declared in one of its manifestos ‘Long live degenerate art’, in a direct challenge to Nazi edicts.

The movement’s leaders were the poet Georges Henein (1914-1973) who spent time in Paris with the surrealist theoretician, André Breton, the painter André Masson and the painter and filmmaker Kamel el Telmisany (1915-1972).

The overwhelming majority of the relics of this movement have been lost in the mists of Egyptian history.

Bardaouil and Fellrath had even locate photos and documents in local antiques dealers to retell this forgotten history.

More broadly, and much to their credit, the Pompidou exhibition advances research in Middle Eastern modern art, a field where knowledge remains extremely patchy.

Before paring back its involvement in art, Qatar, and in particular the Mathaf museum, offered a glimmer of hope that significant research efforts in the field might get the green light.

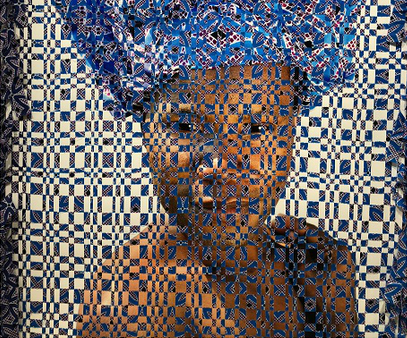

Egyptian surrealism distinguishes itself from French surrealism, whose founder was André Breton, through its desire for social justice, influenced by communism, as well as by its expression of a lively local culture that makes reference to ancient Egypt.

The result is breathtaking, giving rise to several masterpieces by names unfamiliar to us.

Such is the case with Samir Rafi (1926-2004) who was based in Paris from 1954 and whose ‘Nus’ (1945) depicts a war zone where fragments of naked female bodies are concealed by great shocks of red hair. Cannons, black birds, silhouettes in flight, a glowering sky… It’s an imaginary and apocalyptic vision… The canvas is owned by Sheikh Hassan Al Thani, a member of the Qatari royal family.

Mayo (1905-1999) hung around with the leading lights from Montparnasse between 1923 and 1927 also lived occasionally in Cairo.

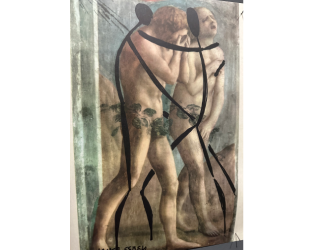

In 1937 he painted the remarkable ‘Coups de Bâtons,’ composed of pastel-coloured stretched forms in movement, like bodies torn to pieces that seem to be involved in some violent game.

As for Ramses Younane (1913-1966), he elaborated a theory called ‘subjective realism’ illustrated in a painting from 1939 which could be a mix of Salvador Dali and Yves Tanguy but illustrates the myth of the Egyptian goddess Noor. This canvas is also owned by Sheikh Hassan Al Thani.

In 1940 Georges Henein wrote from Cairo, ‘At a time when almost everywhere in the world people are only heeding the sound of cannons, it is necessary to give a certain artistic spirit the chance to express its independence and vitality.’

The words still hold true 77 years later.

Until 17 January. www.centrepompidou.fr

The show will travel to Reina Sofia in Madrid, K20 in Dusseldorf and Tate Liverpool.