Biographers and trends

No one should believe that art history presents a fair view of artistic creation. Artists’ legacies wax and wane according to the changing tastes of biographers and trends. Such is the case for the German artist Albrecht Altdorfer (1480-1538), who is the subject of an exhibition at the Louvre comprising 200 works, including many drawings and etchings currently closed for an indefinite period due to the lockdown.

Rehabilitating this genius

In the 16th century Altdorfer developed his own exceptional artistic genre, placing nature at the centre of his works. His landscapes are powerful, lush, and oversized, with human figures depicted as tiny, trivial beings overwhelmed by their surroundings. Sometimes Altdorfer would erase any inhabited presence from his mighty rural representations – the first time this had happened in the history of western art. The Louvre is therefore rehabilitating this genius.

A star but only in Regensburg

This painter, who perhaps first trained as a miniaturist, went on to be a public figure in the town of Regensburg in south Germany. No published memoirs or external testimonies survive about this great man… The little we know of him pertains to his activities as a citizen and not his career as an artist. But the art market was booming at the time, and the painter attempted – according to historians – to ride this lucrative wave. But to Altdorfer’s misfortune, there were other cities in this part of Europe around the same time where two giants of personal promotion and business sense were working away, two German artists who are well established in collective memory: Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) and Lucas Cranach (1472-1553). Sandwiched between these two men who were rich, famous, and savvy, it didn’t leave much space for him to be remembered.

Dürer and his marketing strategy

To popularize his iconography, Dürer (see the report about his exhibition at the Albertina in Vienna) set up an exceptional means of image production. The art historian Christof Metger explains: “This kind of art was gradually transformed into veritable mass media. Images, for the first time in history, became truly commercial products.” The hundred etchings he created were sold across the whole of Europe. Dürer even hired an agent for this very purpose who travelled all the way to Italy to sell his precious papers. Dürer developed his own cult of personality, often depicting himself as a kind of saviour deity through his art. But in the case of Altdorfer, there are no known self-portraits. Dürer recorded his thoughts on painting, his travels… whereas the Regensburg native remained mute in the face of history.

Julia Zaunbauer

Dürer created what we would nowadays call a logo: a highly distinctive monogram which featured on each of his works, rendering them instantly identifiable. Julia Zaunbauer from the Albertina in Vienna explains that Altdorfer, “who was heading for the same success”, only had to copy Dürer’s idea by simply changing the AD monogram to AA.

Séverine Lepape and Hélène Grollemund

For two of the curators of the Louvre exhibition, Séverine Lepape and Hélène Grollemund, “it’s entirely probable that the two artists could have met. But Dürer didn’t generally write about his rivals.”

Cranach productivity

As for Cranach, to illustrate his desire for productivity we could point out that his tomb at Weimar bears an epitaph in homage to the speed at which he painted: “Pictor celerrimus”. Altdorfer was only a local celebrity in Regensburg, even though he worked for Maximilian I, the Holy Roman Emperor. It was this monarch who also asked Cranach to illustrate his prayerbook. Cranach had a vast clientele and a large studio where he produced his series of female nudes representing rotations of Venuses, Eves or Judiths.

An ear to the market

Much more modestly, Altdorfer was also an artist who had “an ear to the market”, as Julia Zaunbauer explains. “He knew how to adapt to new conditions of artistic production, specializing in prints and collectable objects to respond to an expanding market.” He developed two major specialities which made him commercially visible to the public. The first speciality was, as the two curators of the Louvre exhibition explain, extremely small artworks, serving as minute gems of precision.

The absolute masterpiece

Within this genre his absolute masterpiece is a painting made in 1529, “The Battle of Alexander at Issus”. It is 1.58m high and depicts countless soldiers following the order of Alexander the Great, marching triumphantly. Overhead there are burning skies and a lyric. This work, which is the “Mona Lisa” equivalent is at Munich’s Pinakothek but Altdorfer – still in his miniaturist niche – developed mini-etchings demonstrating his excellence in a section of the market where Dürer was absent. His languid Venus engraving measures only 2.8 x 6.8cm and his highly detailed “Landscape with spruce and two willows”, which he carefully coloured in with watercolour, measures 11.4 x 16.1cm.

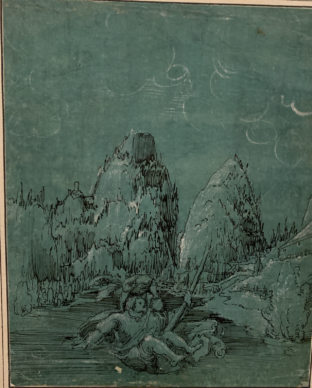

An impression of chiaroscuro

Altdorfer developed another original creation: drawings on coloured paper. Monogrammed and immaculate, they were clearly destined for commerce. The idea was to create an impression of chiaroscuro by first painting the paper with a relatively transparent wash. Against brown or blue backgrounds, the black line of the pen heightened with white gouache displays a fantasy atmosphere with the scene of “Abraham’s Sacrifice”, situated in a palatial setting invaded by nature, or “Wild folk family” surrounded by gigantic trees. It’s an extraordinary technique.

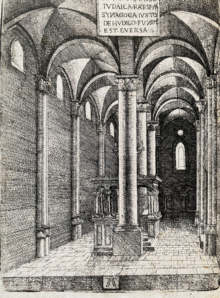

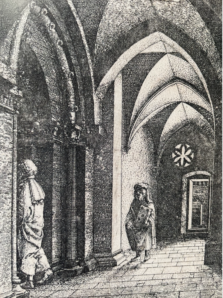

Hostility towards Jews

Finally, as the curators Séverine Lepape and Hélène Grollemund observe, you might think that the fact that Altdorfer was posthumously enlisted at the beginning of the 20th century as the leader of the national movement of the “Danube School”, charged with demonstrating German superiority, does not play in favour of his return to glory. In his day, Albrecht didn’t hide his hostility towards Jews. In Regensburg on 21 February 1519, while the town synagogue was being destroyed, he immortalized the event by drawing the building in two etchings, accompanied by the comment: “by the just judgement of God”.

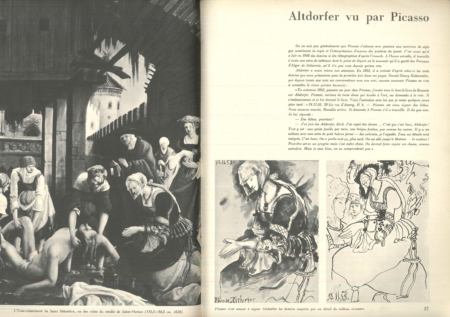

Titian, Ernst, Picasso

L’oeil. 1955

Nevertheless, Altdorfer would go on to leave an important legacy for other artists. We know that Titian copied one of his etchings and in the 20th century the surrealist Max Ernst cited him as one of his favourite artists. Picasso even took it upon himself to copy his “Saint Florian Altar”. In 1953 the Spaniard said with regards to this work: “I’ve been copying Altdorfer. It’s really fine work. There’s everything there – a little leaf on the ground, one cracked brick different from the others (…) It’s beautiful.”

Donating=Supporting

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.