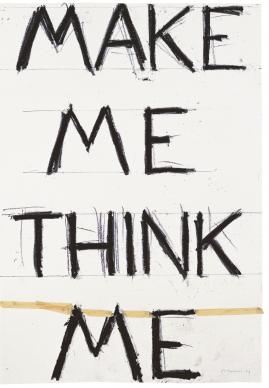

Bruce Nauman is a towering figure in the art world but Bruce Nauman is also a mystery, for he is a complex artist.

From 21 October, Moma in New York is dedicating its entire sixth floor as well as its PS1 spaces to him for a huge and well-deserved retrospective. Moma has over 80 artworks by Bruce Nauman in the collection.

In the meantime, you can visit Basel in Switzerland where you can see the same retrospective more or less in its entirety with 170 artworks displayed in the exhibition space resembling a mausoleum designed by Herzog & de Meuron: the Schaulager.

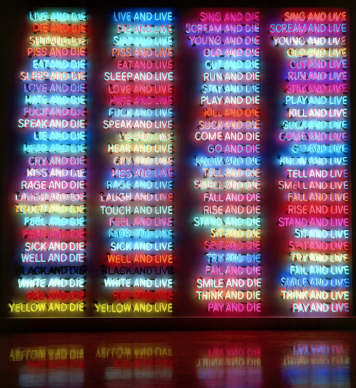

During his 1994 retrospective, also at Moma, I’d had a similar feeling: Nauman invented everything – or almost – before everyone else (video, neons, etc) in an artistic register that was at once sensitive and conceptual.

This time, armed perhaps with my experience, I also understood that Nauman had carefully studied art history, from the images of Etienne-Jules Marey or Eadweard Muybridge to the sculptures of Matisse, Moore and the Dada artists, via Marcel Duchamp and Joseph Beuys.

One of the curators of the Basel incarnation of the exhibition, Isabel Friedli, explains what makes Nauman a major artist today:

Nauman may be classed as an American artist in that he lives in America, but his language is more universal than that for he is also an intellectual artist with a great deal of irony and nuance, which make him seem European.

Nauman is not an artist whose work should be seen through reproductions. You must have the full Nauman experience.

As Kathy Halbreich explains – lead curator of the show currantly on. She curated the first Nauman retrospective in 1994 but is now the director of the Rauschenberg foundation – in the hefty 2018 catalogue: “Much of the literature on Bruce Nauman either criticizes or celebrates the lack of conceptual and stylistic coherence in his work”.

In Basel, Isabel Friedli explains the idea behind the exhibition:

In defining Nauman’s work, Kathy Halbreich found a common theme for the majority of his artworks: disappearance.

This phenomenon also gives the exhibition its title: “Disappearing Acts”. She illustrates this idea, among others, through the amusing example of his 1966 piece, “Wax Impressions of the Knees of Five Famous Artists”: “the material is not wax and the knees are all his own”. Don’t go believing what artists tell you…

For me, the common theme that unites most if not all of Nauman’s work is his observation of the various interactions available to us as human beings.

– Man’s interaction with his genitals and with other men and women’s genitals. Example: “Punch and Judy Birth & Life & Sex & Death” (1985).

– Man’s interaction with objects. Example: “Spilling Coffee Because the Cup Was Too Hot” (1966).

– Man and his voice. Example: “Good Boy Bad Boy” (1985).

– Man and his mouth. Example: “Myself as a Marble Fountain” (1967).

– Man and his hand. Example: “All Thumbs” (1986).

– Man and his mind, his ability to conceptualize something that doesn’t exist. Example: “Model for Trench and Four Buried Passages” (1977).

– How man identifies with the lab rat. Example: “Green Light Corridor” (1970) or “Learned Helplessness in Rats” (1988).

– Man and animal suffering. Example: “Carousel” (1988).

And so on and so forth…

Nauman is an explorer of humankind.

I do, however, remember being disappointed by his sound installation in the Tate’s Turbine Hall in 2004-2005, which emitted recordings of 25 spoken texts conceived earlier on in his career. One disappointment among many excellent surprises…

Glenn D Lowry, the director of Moma, observes that “Nauman’s work teaches us that making and thinking about art involves all parts of the brain and body”.

In actual fact Nauman reconciles our bodies with our brains.

In doing so, he goes against the puritanical thinking that wants the brain to be a separate entity, detached from the rest of the body; the kind of thinking that wants the hand not to go near the genitals and if it does then on no account should it be spoken about.

Ultimately, like all great creators, Nauman is not primarily concerned with disappearance but rather with the more or less diffuse formulation of what we already know and to which he gives a form.

He could be a Marcel Proust of the visual arts from the latter part of the 20th century, highlighting each of the tiny mechanisms that make up our behaviours.

“The true artist helps the world by revealing mystic truths” he writes in a colourful, spiralling neon work from 1982.

Ultimately, Bruce Nauman is a “Good Boy Bad Boy”, to quote the title of his 1985 video.

In an archaic spirit which runs contrary to that of the exhibition, Schaulager did not permit the taking of photos or videos.

Until 26 August. Schaulager. Basel. www.schaulager.org

From 21 October to 25 February, Moma & Moma PS1

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.