The “weaker” sex

One good thing about trends is that they can lead us to rediscover certain major artists who have spent too long under the radar. This is true of Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) who, within the official narrative of the early 20th century avant-garde, displays several handicaps: she was a woman, she had a certain unusual flair, and she was American. Museums the world over are currently determined to showcase more artists from what was once called in French, the “weaker sex” (le sexe faible), and here she is in the limelight in Europe (Madrid, Basel, and Paris).

Didier Ottinger

Her long-time champion, art historian Didier Ottinger, is presenting an absolutely exceptional retrospective of her work at the Centre Pompidou, which runs until 6 December and features 80 works.

Visual delight

The appeal of the show lies in the fact that the choice of works and the layout are a visual delight, but they also allow the visitor to understand the painter’s approach.

Alfred Stieglitz

An exhibition at the Tate Modern in 2016 presented her work in the company of her husband, the remarkable photographer and modern art promoter Alfred Stieglitz. That show was less impactful. Because O’Keeffe is more than enough by herself.

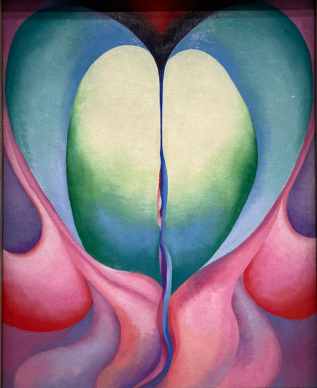

Flower power

The artist is primarily associated with the paintings that she made over a long period: images of flowers that she started painting from 1919. They are depicted as a group of colourful volutes surrounding the pistil at the centre.

Eroticism

They are often likened to representations of female genitalia and Georgia would grow tired of this interpretation, which caused a scandal at the time. All the more so in New York in 1921 when her husband staged an exhibition featuring nude photos of her, concealing nothing of her intimacy.

Publicized

As Didier Ottinger explains: “Overnight Georgia’s image became highly publicized and associated with sensuality.” Their correspondence also reveals a flourishing physical relationship between the painter and her husband, who was 23 years her senior.

Not Cézanne

The source of the American artist’s inspiration was not, as was the case for so many of her contemporaries, the transformation of shapes derived from the teachings of Cézanne, whose advice was to “treat nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone”.

With Kandinsky

She preferred to respond, like Kandinsky, to “what proceeds from an inner necessity of the soul.” Six months after its publication in Munich in late 1911, the pages of Kandinsky’s book-manifesto, “On the Spiritual in Art and in Painting in Particular”, were first translated into English by Stieglitz himself.

Mythology

Didier Ottinger writes in the catalogue: “The day the gallerist discovered O’Keeffe’s charcoal sketches was one of those moments when history tipped over into mythology. Stieglitz’s love affair with O’Keeffe’s drawings opened up one of the most promising chapters in American contemporary art.”

Accepting my thinking

The artist is extraordinary free. She said: “I decided to start anew – to strip away what I had been taught, to accept as true my own thinking. This was one of the best times of my life. There was no one around to look at what I was doing, no one interested, no one to say anything about it one way or another. I was alone and singularly free, working into my own, unknown – no one to satisfy but myself.”

Rodin drawings

It is interesting to note that everything in her work revolves around the subject of sensuality. Her first real visual shock came when she saw Rodin’s drawings. The sculptor produced an extensive series of works on paper depicting women in acrobatic positions, arched as though in the throes of pleasure.

Sensations

In O’Keeffe’s work the colours are arranged to tell stories that are not, strictly speaking, abstractions, but which correspond rather to sensations.

Codification of colours

Kandinsky had already codified the use of colours: red was “the colour of an ardent life”, “absolute green is the most restful colour”, “yellow is the typically earthly colour” of late summer etc…

New Mexico

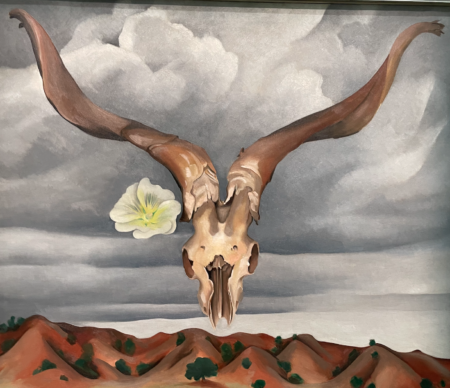

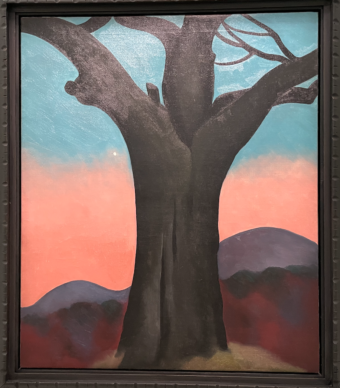

In 1929 she found the place where she felt “at home”, in New Mexico. She bought a house there in the middle of the desert. Her landscapes frequently resemble parts of the body.

Men are trees

Her portraits of men take the form of trees. During the war she was inspired by animal bones, as in “Pelvis with a Distance” from 1943 depicting bleached cow bones against an azure sky, which resembles a surrealist landscape with Daliesque stretched forms.

Terracotta

Towards the end of her life Georgia O’Keeffe, who was going blind, decided to make sculptures. One of her final works, displayed at the Centre Pompidou, is a terracotta piece that resembles a womb. Even in old age, her inspiration remained the same.

Georgia O’Keeffe. Until 6 December. www.centrepompidou.fr

Donating=Supporting

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.