Paul Cézanne father of all

“Everything in nature is modelled on the sphere, the cone and the cylinder. One has to learn to paint from these simple shapes”.

It’s 1904 and the artist writing these words, the Aix-born Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), has been doing a lot of painting in a little house located right in the middle of the Bibemus quarry, where the rocks coincidentally take the form of squares and rectangles.

They’d been hewn in this way a century earlier in order to extract the stones that would be used to construct the beautiful buildings in the town of Aix. Paul Cézanne, the man Picasso once described as “father to us all”, is therefore the godfather of cubism, as explained in the remarkable exhibition of 300 works dedicated to this revolutionary movement (1907-1917) at the Centre Pompidou until 25 February.

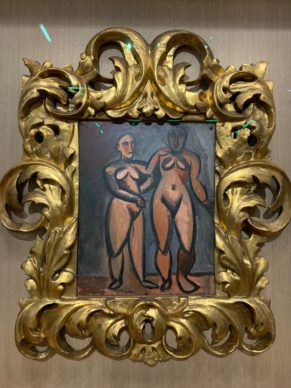

An entire room displays his influence alongside that of another great figure, Gauguin, who drew inspiration from the so-called primitive arts in his sculptural work. Their observations and the discovery of African and Oceanic art resulted in Picasso, from 1906-1907 onwards, creating women whose heads resemble African masks and whose dancing bodies can be traced directly back to the “Bathers”, which Cézanne painted repeatedly.

Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, a revolution in art

In fact, the whole thing first played out between Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and Georges Braque (1882-1963), two young friends – talented, idealistic and close – who sought to bring about a revolution in art.

The artistic community in Montmartre couldn’t help but notice their aura. And the collectors Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo supported the “movement”, as did the dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler who handled the business side.

The exhibition assembles a breathtaking array of modern masterpieces, such as Braque’s cubist landscapes in Marseille in the district of L’Estaque in 1908, when he started following in the footsteps of Cézanne.

“Representation in painting had to be destroyed within the context of the increasing importance of photography and cinema,” explains the curator Brigitte Leal.

This was the great liquidation of optical conventions. The shapes splintered into pieces as though under the effect of multiple kaleidoscopic visions.

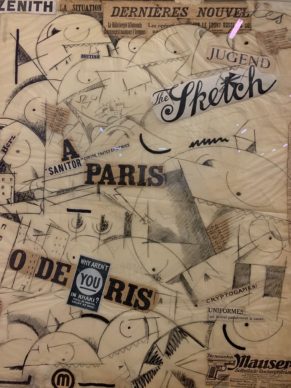

From 1909 the volumes were pulverised into a multitude of juxtaposed transparent facets.

A few realist details or words serve as reference points.

The colours are muted. This is cubism’s so-called analytical period.

The power of the genre was pervasive within artists’ circles and from Robert Delaunay to Fernand Léger, Marc Chagall to Constantin Brancusi via Picabia, they each created their own interpretation of cubism.

From Duchamp to Malevich

The intentions are more disorganized towards the end of the exhibition, which finishes with the last evolutions of cubist influences.

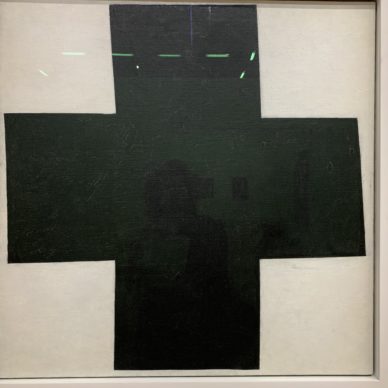

From Marcel Duchamp’s bicycle wheel in 1913 to the “Black Cross” on a white background by Kazimir Malevich in 1915, they all produced works “modelled on the sphere, the cone and the cylinder” before embarking upon their own journeys of experimentation.

The war, with its vast mass graves and its deep sense of disillusionment, would once again result in a remodelling of the spirit of the artists of the avant-garde…

Until 25 February, www.centrepompidou.fr

The exhibition will be displayed at the Kunstmuseum in Basel from 31 March to 5 August 2019.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.