Strange and glorious

The American artist David Hammons (born in 1943) is a strange and glorious figure, frequently absent, yet always seeming to appear where he’s least expected. He isn’t affiliated with any one gallery, and what we know of him is largely limited to now outdated images of a man selling snowballs in the street.

A star

David Hammons

But the artist is much more than a melting ice salesman. He occasionally graces certain galleries with unexpected appearances. David Hammons, who frequently addresses the reality of life for black people in the United States through his readymades, has himself overcome difficulties in an extraordinary way: his intermittent presence has made him a star.

Important documentary

A documentary about him has just been released and it really is important. It was made by the New York journalist Judd Tully, who I have known for a long time (when we were both working for the great Bruce Wolmer, editor of Art &Auction), together with the documentary filmmaker Harold Crooks. It doesn’t address his private life but rather the origins of the oeuvre of the one of the most important creators of the late 20th century. It’s called : The Melt Goes on Forever: The Art & Times of David Hammons.

From Jazz to Arte Povera

David Hammons

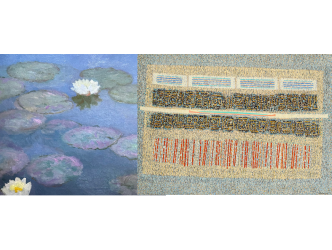

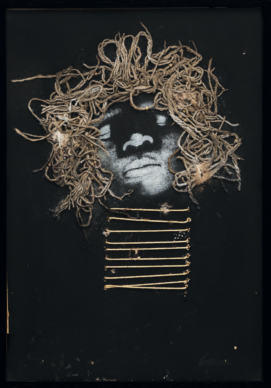

It gives us the opportunity to learn that his work is at the crossroads between Marcel Duchamp’s readymades, Arte Povera, traditional African art, and is also largely influenced by jazz. Certain institutions were not wrong on this, such as the Glenstone collection near Washington, the Whitney Museum, the Pinault Collection in Paris and Venice. And Moma in New York, who gave him a carte blanche exhibition in 2017… On this occasion, Hammons hung a work by the African American artist Charles White (1958-2023) opposite a drawing by Leonardo da Vinci.

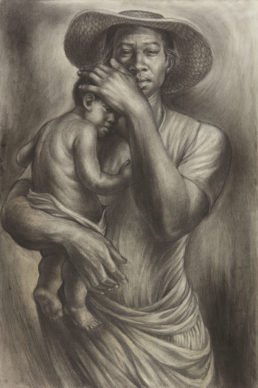

Charles White

Charles White

The African American artist Suzanne Jackson (born in 1944), who was a student with him at the Otis College of Art & Design in Los Angeles, reveals that their professor was in fact Charles White: “Until he met Charles White, he did not know any black artists.” People are also often unaware of the African American artist Noah S. Pirufoy (1917- 2004) who lived in Los Angeles and has, among other things, used found objects from the Watts Rebellion in 1965 in his work formed of assemblages. Obviously he was also a notable influence on Hammons. He states: “I’m interested in the beauty of poverty because there’s a pureness (…) There’s always a beauty which goes with the madness.”

You have to be a genius

David Hammons

In 1992 David Hammons took part in one of the most prestigious artistic shows of the time: Documenta 9 in Kassel directed by Jan Hoet. It was on this occasion that his impact became international. At this time Hammons truly defined his research: “In this culture you’ve got to be a genius, to think, to learn their shit, practice their way of culture and their culture and yours and go beyond your culture and their culture to a new culture.” A theory that has major similarities with the Brazilian poet Oswald de Andrade’s “Cannibalist Manifesto” (Manifesto Antropófago) from 1928, which transposed the idea of cannibalism to the cultural field. One must digest the other to become oneself.

Old interviews

David Hammons

The documentary is also captivating in terms of what it sheds light on through old interviews with this ever playful artist, and includes commentaries from people close to him. The poet Steve Cannon, for example, reveals that: “The more he says ‘fuck off’ to the art world the more they want him.” This seems to be very much true when we think for example of the 2007 exhibition at L&M Art in New York, when he was content to exhibit vandalized fur coats spraypainted with the names of artists.

Judd Tully

Judd Tully answered my questions via video. He never expected Hammons to take part in the documentary but from the very beginning he knew of the project’s existence. “We interviewed over 30 people. We have worked on the subject for 10 years.” He reveals that the mysterious figure gave a fairly positive reaction after having seen their work.

Day’s End

It is most likely for chronological reasons that they don’t address the recent and most ambitious project ever made by Hammons: Day’s End, dating from 2021. (They finished filming in January 2020). In collaboration with the Whitney Museum he created a spectacular and characteristically phantom-like work made from 15.2 x 113 metres of steel tubes (see the report about Day’s End here). It’s an homage to another artist who is now deceased, an American who is still not widely known, Gordon Matta-Clark (1943-1978), who made sculptures on an architectural scale. More specifically, Hammons’s “Day’s End” is a kind of ghostly readymade of an artwork made by Matta-Clark in 1975.

David Hammons

Where to find “The Melt Goes on Forever: The Art & Times of David Hammons”

- Apple TV

- Amazon Prime

- Kinema

- or check for upcoming screenings here

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.