Imagine an artist who would become a legend within the first decade of his career.

What would he do with the rest of his life?

In the contemporary period, we could say that Damien Hirst (born in 1965), who was a world-renowned star during the 1990s and the most famous of the Young British Artists, was a textbook case. The rest of his artistic output hasn’t always been glorious, and his successes have largely been based on repetitions of his early ideas (with the exception of a huge and unique production last year at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice9.

The same thing happened to the celebrated Eugène Delacroix a century and a half earlier, only with added genius.

How do you settle into a long life as a painter after an enormous early success? The answer can be found at the Louvre, then the Metropolitan Museum in New York, illustrated in a masterful retrospective of 180 artworks co-organized by the director of the museum’s paintings department, Sébastien Allard. It must be noted that, like Damien, Eugène had a fervent desire to succeed and, like the English artist, he courted controversy.

Sébastien Allard, however, introduces certain nuances into this comparison.

To achieve his aims, Delacroix would go on to cause a sensation at the “Salon”, the major exhibition in Paris at the time.

He said: “I shall either be Poussin or nothing. Success, for me, is not just an empty word.” Delacroix thought of nothing but his art, frantically. He literally threw himself onto the canvas to give shape to the colours.

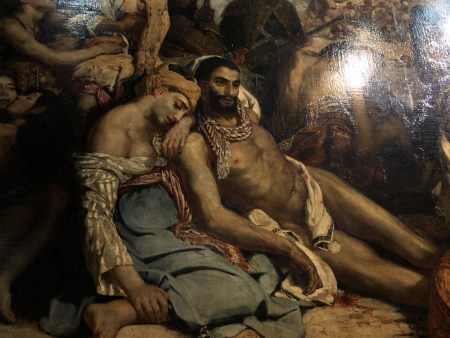

He was 24 years old when he made a painting 4.19 metres in height of a real event: “Le Massacre de Scio”, a Turkish bloodbath in Greece perpetrated two years earlier.

He was 29 years old when he painted at nearly 5 metres in height a decadent vanity of an Assyrian king who ordered the suicide of his entire court around him. He literally exploded the principles of classical composition. The painting no longer had a centre. He wanted to express chaos. As for the women, they offered up their sensual, undulating bodies to death. An orgy of final moments.

Finally, when he was scarcely 32 years old, he painted the great emergence of the popular revolutionary, the bare-breasted figure who would go on to become an absolute icon from the third republic onwards, “La liberté guidant le peuple” (Liberty Leading the People).

To sum up: violence, sex, and passion were drawn from his great masters, who were Poussin and Rubens.

Delacroix already knew that he would go down as one of the greats in the history of art. But beyond that there was also his genius in the subtle mixing of colours.

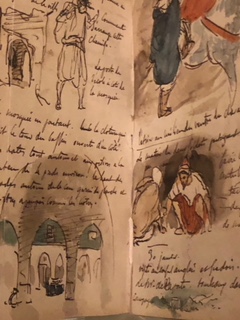

In 1832 he embarked upon a journey through Morocco and Algeria which would confirm his extraordinary gifts as a colourist. “Les femmes d’Alger “(Women of Algiers) would become a reference work for both Cézanne and Picasso. This work is proof that Delacroix could also attain the sublime without resorting to tragedy.

Here, three unassuming women in a symphony of warm tones are presented seated.

Sébastien Allard explains the genius of Delacroix

A small section of the exhibition is dedicated to an anomaly in the Romantic artist’s production: a series of kitsch bouquets of flowers inspired by nordic painting. A misstep that is once again reminiscent of Damien Hirst, who sometimes evokes the painting of Francis Bacon, other times a decorative abstract pointillism in candy colors as in his recent paintings. shown now at Houghton Hall in England (1)

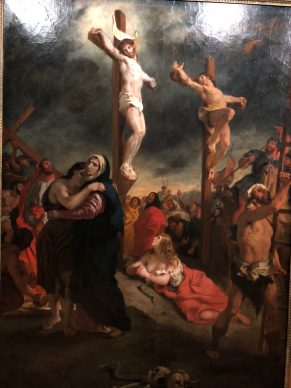

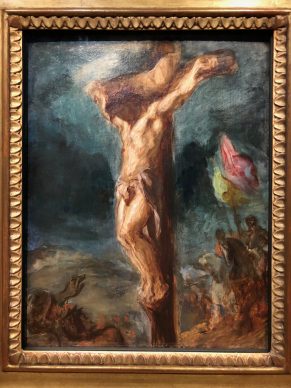

But this retrospective at the Louvre also shows another little-known production of his, which he was creating almost in parallel: exceptional crucifixions to link to his monumental commissions for public buildings and churches, which would occupy him towards the end of his life.

In 1859 Delacroix responded to a compliment from the poet and art critic Baudelaire with the curious line: “you treat me like only the great dead are treated.” Delacroix entered too early into the pantheon of great painters. This was the tragedy of his life.

Until 23 July. www.louvre.fr

The exhibition will be held at the Metropolitan Museum in New York from 13 September 2018 until 6 January 2019. The biggest artworks from the Louvre won’t be travelling, with the exception of the “Women of Algiers”.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.