Are these simple subjects for a simple painter? Not at all.

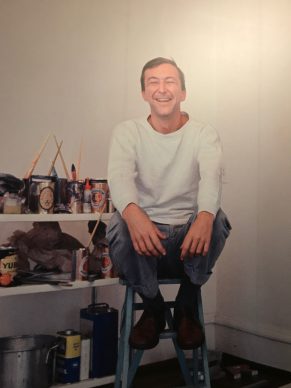

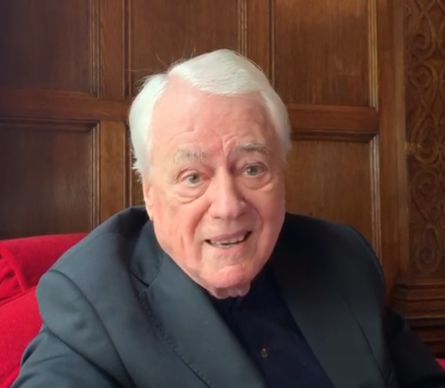

Since the 1950s, when Jasper Johns (born in 1930) develops a unique language using familiar themes, his vision is so powerful that paintings of targets, numbers or flags have now become synonymous with none other than… Jasper Johns.

In 1969 he explains his choices: “I’m interested in the idea of sight, in the use of the eye.

I’m interested in how we see and why we see the way we do”.

He also refers to “Things the mind already knows”.

As an artist Jasper Johns is conceptual, cerebral, and analytical, with a choice of subjects that sometimes recalls Pop art.

But Roberta Bernstein, co-curator of the exceptional exhibition that has just opened at the Royal Academy in London before it is due to travel to The Broad in Los Angeles in February, rejects the latter categorization.

She emphasizes that Johns is a true painter who has no desire to simulate the workings of machines or technology in his creations.

The exhibition, which features 150 artworks, is remarkably conceived in that it very explicitly merges themes and chronology.

Roberta Bernstein outlines the aim of the exhibition:

The show opens wittily, going straight to the point with a multicoloured target painted in 1961.

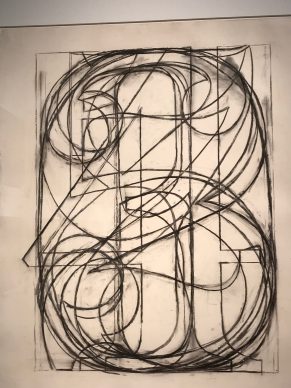

The section dedicated to “figures” is exceptional. Or how an artist endlessly reinvents the same theme over time.

There are painted numerical figures juxtaposed as though scrolling electronically and figures overlaid from 0 to 9. There are figures in multicolour and in black and white. There are painting-sculptures in bronze or metal and there are drawings, and prints.

The numerical figure is used as a pretext for working on form and also as an exercise in looking.

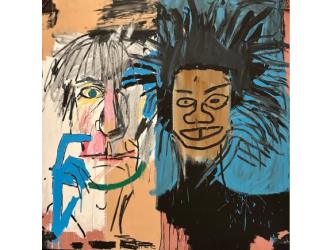

Johns’ canvases can also be encrusted with objects: brooms, the legs or arms of mannequins.

To the extent that certain canvases could almost be mistaken for the late combine paintings of Robert Rauschenberg.

Roberta Bernstein explains the relationship between the two artists:

Sha also says:

They shared the same studio and that it was there, in 1958, that Leo Castelli noticed Johns before staging his first exhibition at his gallery.

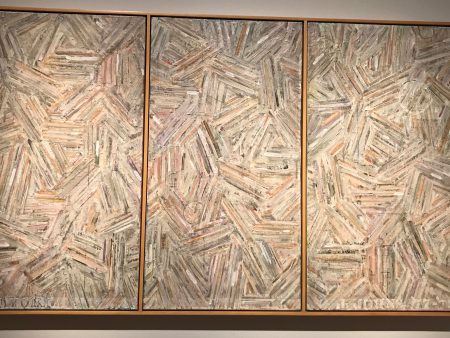

From 1972 Jasper Johns employs a new crosshatching motif, which he first glimpsed as a pattern on a car and would go on to see again later – coincidence? – in a self-portrait painted by the Norwegian master, Edvard Munch.

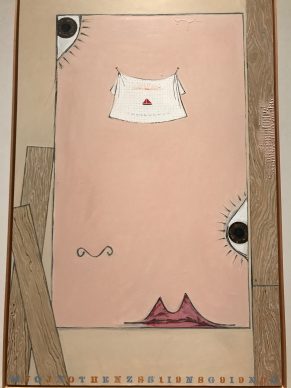

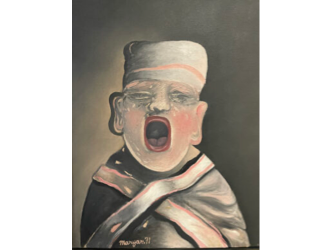

This is how we arrive at the paintings from Johns’ later phase: a hybrid creation, verging on surrealist.

This phase is haunted by the analysis of psychological and memory mechanisms.

Roberta Bernstein explains that while he was in the army he read an article on Bruno Bettelheim and how the psychiatrist had treated a young schizophrenic patient.

The figures in the painting are based on the photos that accompanied the article.

Johns made use of them unconsciously, only to remember that years later.

It is difficult to make the link between this Jasper Johns and the artist who made the numerical sequences.

Roberta Bernstein concludes simply that if he has up until now achieved fame for his historical series from early on in his career, she is convinced that the future will enable the rediscovery of these paintings, made by assembling the memories of images.

The exhibition at the Royal Academy even exhibits an artwork dating from 2016.

Jasper Johns is 87 years old. At an age when many men suffer from memory loss, his memory bank is still growing, on canvas.

Until 10 December. www.royalacademy.org.uk/exhibition/jasper-johns

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.