Julian Schnabel is endearing. He’s sensitive, sweetly fragile and slightly grouchy. He’s also an enthusiast.

His exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay allows us to “change how we see things,” as I was told during an informal conversation with Sébastien Allard, head of the paintings department at the Louvre.

I’m not always fascinated by his paintings, but I must acknowledge that exhibiting for example his “Portrait of Tatiana Lisovskaia as the Duquesa De Alba II” painted in 2014, a large canvas with what looks like a rip down the middle depicting a small, slender woman in black, alongside “La dame aux éventails” (Woman with Fans) from 1873 by Edouard Manet, produces an astounding effect that is almost inexplicable. The two paintings, although different in size, both have backgrounds in similar shades.

But most significantly it was Manet, one of the “inventors” of modernity, who made the link between Goya, whom he studied a great deal, and the rest of art history.

Schnabel is inspired by Goya. Manet was inspired by Goya, and these two women are placed side by side.

Schnabel encourages us to look elsewhere in painting.

He has gone “fishing” in the vast collection of one of the most beautiful museums in the world, like that of the extraordinary mini canvas (31x25cm) in which Paul Cézanne tells the story of “La femme étranglée” (The Strangled Woman).

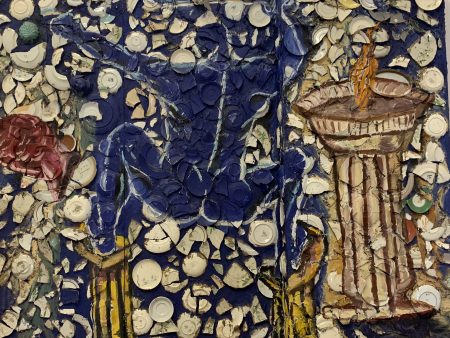

Clearly the motifs of “Les Dindons” (The Turkeys) from 1877 by Claude Monet dialogue perfectly with Schnabel’s “Rose Painting” from 2017, which features plate fragments incrusted on the canvas.

Here the painter also opens up a little: he refers to his father with a bronze piece depicting his father’s head dating from 2004.

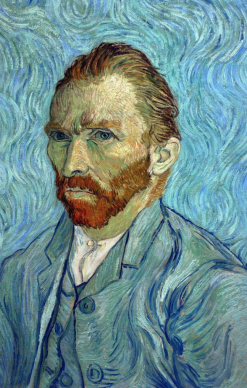

There’s a Van Gogh in his exhibition that couldn’t be more revealing: a self-portrait against a blue background from 1889. Not far from this there’s a symbol of friendship: “Les Alyscamps” painted by Paul Gauguin in 1888 when he came to join his fellow painter in Arles.

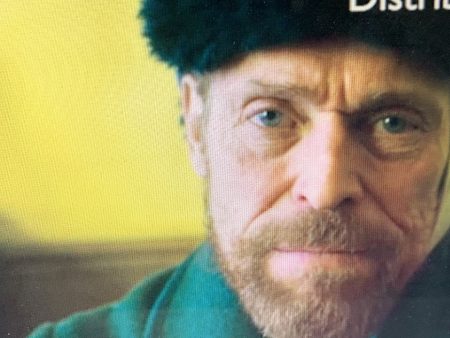

The exhibition is of course directly linked to his film “At Eternity’s Gate”, a stylized biopic on the life of Vincent Van Gogh, which I was able to see after the interview with Julian Schnabel.

It focuses primarily on his period in Arles. The film, which had its theatrical release on 16 November in the United States and will be showing in Europe from January, is largely concerned with the suffering of painting.

This is a film by a painter about a painter.

As it happens, Schnabel has deliberately taken liberties with the artist’s biography. Van Gogh didn’t paint his shoes at Arles, yet this is what the artist shows…

Schnabel wishes to communicate something else. And Willem Dafoe is a pure and perfect incarnation of Vincent Van Gogh.

On Artnet News on 15 November Ai Weiwei, who is a friend of Julian Schnabel (I recently curated an Ai Weiwei exhibition at the Mucem in Marseille which closed on 12 November), summed up the spirit of “At Eternity’s Gate” well: “I think this film is basically a self-portrait. He just wants to experience what painting is, why painting matters.”

I tried to ask Julian Schnabel a series of six filmed questions in one minute, but he refused.

He doesn’t like to be filmed. “It’s not natural for me.” So I recorded him instead. But in the end, for the final question on what image he wants to leave behind, he gave in.

Julian Schnabel wants to be remembered as a painter.

JBH: Who is Van Gogh?

JS: It’s very difficult to say who he is.

JBH: So why did you choose him?

JS: Um… Because maybe it’s impossible to make a film about Van Gogh. Are we talking about the film or are we talking about the paintings right now?

JBH: Both.

JS: His paintings speak to me. And making a film about him was a way to talk about painting, and talk about life, through him. He had a vision of the world and a vision of a way to paint. And at the time other people didn’t seem to be able to see what he was seeing. He couldn’t stop doing what he was doing anyway. He personifies the chasm between the artist and society. I mean, the movie is called “At Eternity’s Gate” for a reason. Because he’s communicating with people past the grave. Art transgresses death. If you look in this room (author’s note: at the Musée d’Orsay), there are all these people; some are dead, some happy to be alive but they’re all speaking to each other. Living ghosts with privileges.

JBH: And even your father is here, right?

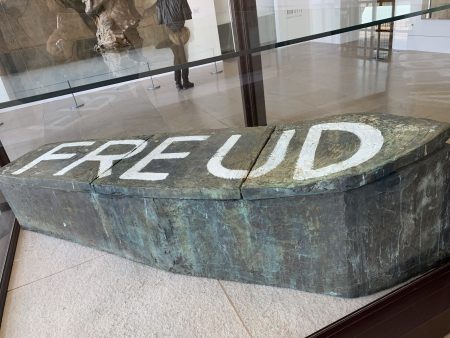

JS: Yeah my father’s here, and also Freud, Artaud… It’s very kind of primordial and familial. The selection of paintings are very personal to me. They asked if I wanted to make the exhibition. But when I started to select paintings they said: we can’t, I don’t know if we can move this one…. So I said: maybe don’t ask me to do it if I can’t select the paintings. But Laurence des Cars (1) and people at the museum believed in it. It’s been a great experience.

JBH: You are a painter, but not only a painter, you are also a filmmaker. So how did you decide to be first a painter, before filmmaker?

JS: I never was a filmmaker, I was always a painter since I was little. It’s just something that I always did. But I was a huge movie fan, and I liked to watch movies. I guess when Jean-Michel Basquiat died some people came to interview me about him, saying they wanted to make a movie about him. So I thought I’d help them.

JBH: You thought you could do better than them?

JS: I didn’t try to do better, I just tried to be accurate and so I basically helped – I bought the rights back, rewrote the script and made the movie. I’d never had a camera before, but I knew my topic.

JBH: What about The Diving Bell and the Butterfly? Here you created a super masterpiece which was not about being a painter. And so you became a real filmmaker.

JS: Well, this movie is about seeing. And all of the seeing that I do is informed by my experience as a painter. One of the reasons why I made that movie is because the guy couldn’t move his head. The audience figures he can’t lift his head up. That’s why the heads are cut off, you accept that, so all of a sudden you end up with fragments or slices out of life; things that create an image that you haven’t seen before. So it was a great freedom to do something like that, where you have a moving picture but the subject is not moving.

JBH: But it’s also a huge challenge. And you created a masterpiece with such a story.

JS: Necessity is the mother of invention. But in keeping with what we’re talking about, the opportunity to make a film about painting, about Van Gogh, it’s not just about painting – you actually experience the movie as if you were him. It’s in the first person. When you look at a painting nobody is mediating: you have a direct relationship with that thing. In this film you see what is happening, it’s as if he’s speaking to you or you’re sitting in a room with him, shot in real time.

JBH: But do you have a very different feeling when you are painting as opposed to making a movie? Does it use another part of your brain?

JS: Yeah, probably.

JBH: You are one of the very few artists who have made a good movie.

JS: You know, there’s a line in the movie where Dr Gachet says to Van Gogh, “you’re confusing people and you’re confusing yourself with your paintings”. Van Gogh replies: “I am my paintings. I thought I could give my human brothers hope and consolation.” Gachet says: “What do you mean, hope and consolation?” Van Gogh: “Well, they could feel more alive,” and Gachet says: “You think they don’t feel like they’re alive?” He replies, “Yes I do.” “And you feel like you can made them feel that through paintings?” And he says, “Yes absolutely.” And so I guess that might true about me, too. Through painting you can make somebody feel more alive and maybe also through making a film you can do that.

JBH: But in a very different way?

JS: Yeah, absolutely. I don’t want the films to be paintings and I don’t want the paintings to be films. When I was a kid I saw the “Seven Samurai”, and the way that these Japanese soldiers are driving their horses through the mud, with all this armour… How can a painting compete with that, you know? So the painting has to be still. That’s what painting does. It’s permanent.

JBH: And you like that?

JS: Yes, I do.

JBH: What about motion?

JS: Well, obviously when I decided to make movies I didn’t just feel like telling a story maybe, but I was – and I think Jean Claude Carrière (2) said that – I was interested in how motion affects things, how time undulates or changes things. There are even parts of the movie where the screen goes black and you just hear him talking. It’s sort of like a Jacob’s Ladder effect, and you feel like you’ve been taken out of it, and when you come back you’re more focused. So it’s very experiential, in a sense.

JBH: And what do you think of the two previous Van Gogh biopics, the one by the French filmmaker Maurice Pialat and the one with Kirk Douglas by Vicente Minelli?

JS: When I was little I liked the Kirk Douglas one a lot. I don’t think it’s very good. It’s a cliché. And there’s a lot of crying in it. I love Kirk Douglas, but the movie is not – it’s of its time, you know? The Pialat movie I think is a waste of time.

JBH: Why?

JS: I know French people like it. I think it’s because it’s the anti-biopic and that’s why people like it, because he doesn’t pay any attention to the story of Van Gogh. So why not just call it Mary Poppins? I mean, he could have! I think Jacques Dutronc has a silly look on his face, they talk about inane stuff and I think it’s a waste of time.

JBH: So it’s not about painting?

JS: It’s definitely not about painting. I don’t think Pialat knew anything about painting. In fact, I heard Daniel Auteuil – who once gave a great performance in Jean de Florette – was going to play Van Gogh at first, and then he started making paintings. Maurice Pialat saw them, he didn’t like it, and he fired him! Daniel Auteuil making paintings… It’s a very touchy thing, you know. For all the people that like Maurice Pialat’s movie, I’m glad they do. I tried to watch it a couple of times and I thought it was absolutely a waste of time.

JBH: So now, what is your next dream?

JS: Dream? Oh, I don’t have any dreams.

JBH: You don’t dream?

JS: I dream, but I don’t dream of something that I’d like to have. I try to figure out what I dreamed the night before, when I wake up, but I never really dreamed about something in the future or whatever. I’m very pleased with the present. I have problems like any other person, but I’d have to say thank you for the different privileges that I’ve had. Just to be able to make a black velvet painting and put some white on it, or think that I was free enough to do something like that… Ultimately making art is about freedom. And not compromising, and doing something just because you feel like doing it.

JBH: And not being filmed! What about just one question, which would be: what would you like people to remember about you. How about just filming this one?

JS: Fine, I can give you something.

(1) Laurence des Cars is the president of the Musée d’Orsay.

(2) Jean-Claude Carrière is a screenwriter and director, famous for having worked with Luis Bunuel among others, who collaborated on the screenplay of the film on Van Gogh.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.