Born in Russia

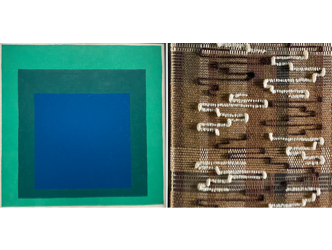

As chance would have it, among the Parisian museums there are two flagship exhibitions this season dedicated to two 20th-century painters, both born in Russia and both émigrés, who went on to have exceptional careers. Their stories also end in a similar way, and it is dramatic: they both took their own lives.

Mark Rothko

On the one hand, from 18 October onwards at the Vuitton Foundation there is a vast exhibition dedicated to Mark Rothko (1903-1970), the painter who left for North America at the age of 10. He rapidly became a star of a new genre of painting, expressed in all its gravity with the aid of a form of abstraction that would nowadays be described as immersive.

Nicolas de Staël

On the other hand, from 15 September the Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris is displaying 200 artworks by Nicolas de Staël (1914-1955), who emigrated to Belgium at 8 years old, then to France once he became an adult. Constant questioning and successive shifts, made in an uninhibited way, from the figurative to the abstract.

Sidney Jannis gallery

The paintings of Rothko and Staël came face to face at least once during their lifetimes. In November 1950, the adopted Frenchman took part in an exhibition in New York titled “Young Painters in the US and France” at the Sidney Janis Gallery, which put artists from both countries side by side. On returning from New York, Nicolas de Staël made very large format works more deliberately.

The famous “Parc des princes”

In terms of this genre, the Parisian exhibition is displaying a legendary painting, “Le parc des princes”, a scene depicting a football match from 1952 that stretches across 3.5 metres in length, composed of blocks of contrasting colours created with a palette knife. The colours are all amalgamated together. It was composed using different layers of thickly textured paint, superimposed. The painting weighs 200 kilos.

Forgotten in America

In January 1951 one of his canvases entered the collections at Moma. A step towards international posterity! But on visiting the museums in the American megacity, specialists indicate curiously that he wasn’t that interested in the major evolutions of painting across the Atlantic. After his death, his oeuvre would even be forgotten there.

Charlotte Barrat

The co-curator of the exhibition, Charlotte Barrat, explains: “This way of painting would become a victim of its own success by leading to multiple preconceptions: as pointed out in the New York Times, “his work ‘suffered also from association with the countless imitators whose cruder handlings of a palette knife became the stuff of tourist galleries from Montmartre to Palm Beach.’”

His son, Gustave de Staël

In fact the Russian émigré, who was orphaned very young, wanted to be seen as an heir to French painting. His son, Gustave de Staël, who was a year old when his father died, talks about a physical rather than an intellectual kind of painting.

1100 canvases in 15 years

Over a fifteen year period, in an absolute frenzy, Nicolas de Staël produced around 1,100 canvases and as many drawings. Here his work is exhibited chronologically. Nicolas did not have a Manichean vision of abstraction and figuration. Everything starts with real visions. He talks about “images of life [that he] receives in masses of colour”. He was on a quest, as his friend the poet René Char explains, for a form of “direct language”. Receiving and transmitting visual sensations, that was his obsession.

1952: 240 works

1952 was a key year in his oeuvre and the Musée d’art moderne demonstrates this magnificently. The artist, consumed by the sacred fire, wanted to literally consume the world, too. He went out and painted small canvases like the impressionists from nature, “sur le motif”. This was how he arrived at the simplicity that became one of his great objectives, in his remarkable Normandy seascapes. At the same time, he also painted a lot on a very large scale, like a scene from the opera, Les Indes galantes, or even a still life with bottles in his studio. 1952 saw the appearance of no less than 240 works.

Sicily and garish colours

From 1954, and for around 24 months, Sicilian landscapes were his obsession. The whole ensemble has a huge visual impact. This is the other masterful group of paintings in the exhibition. Staël visited the Italian island a little earlier with his wife, children… and mistress too. He dared to feature garish colours, like in “Agrigente” with its almond green sky, its lemon yellow expanses and its red or purple forms that he arranged in perspectives. He justified his approach: “By trying to be blue the sea becomes red”.

Painting in cycles

We understand, then, that his career was punctuated by cycles. “He searches, he experiments, then, at a given moment, he creates his masterwork, in the quasi-artisanal sense of the term. And when that is done… something dies, it’s over. It must be broken to move on to something else,” points out the other curator of the exhibition, Pierre Wat.

Lack of selectivity

The last rooms in the museum, dedicated to his final moments, when the painter became lighter, he was returning to using the paintbrush rather than the palette knife and the forms are identifiable once more, but less appealing. They suffer from a lack of space and also perhaps a lack of selectivity that doesn’t always do the artist’s memory justice.

Psychic exhaustion

In 1955, Nicolas de Staël, who then lived in the Antibes, suffered – according to Pierre Wat – “absolute psychic exhaustion”. The man was on his last legs. On Wednesday 16 March at around 10:15pm he threw himself off the terrace of his studio in Antibes. The famous author of the novel “The Stranger”, Albert Camus, commented a few days later on his death with their mutual friend René Char: “The suicide of de Staël has filled me with rage and pity at the same time. I resent him when I think of Jeanne (ed. his wife), and you, and others. In every act of this kind there is a sort of violation carried out against those who are involved, an abduction of their freedom, their right not to know, to be innocent. And this violation, I cannot pretend it doesn’t outrage me. At the same time, I think of him, and of a certain misery that I know well.”

State of urgency

His daughter Anne analyses this dramatic death in the catalogue: “My father had a calling… It was so vital for him to be working in his studio that I felt that, if he hadn’t kept doing it, he wouldn’t have been able to breathe (…) What I mean is that he didn’t have a sense of time. He lived in another time: a time that was so pressing, a state of urgency.”

In Antibes, the terrace where the artist fell to his death is surrounded by a series of windows without fastenings that resemble frames, designed to sublimate the landscape.

Nicolas de Staël. Until 21 January 2024. www.mam.paris.fr/fr/expositions/exposition-nicolas-de-stael

Donating=Supporting

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.