The myth of the artist’s studio

The artist’s studio is a world of its own where they can make and unmake their great universes of visual art. From Rembrandt to Lucian Freud, many of them have been depicted there as supreme creators which lends the place an almost mystical quality. In this respect the major sculptor from the first half of the 20th century, Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957), went even further.

Impasse Ronsin

The Romanian trained as a wood carver in his country and arrived in Paris in 1904 before basing himself from 1916 in three dilapidated adjoining buildings, which he would transform into a kingdom for his sculptures, on the Impasse Ronsin in the district of Montparnasse. With time and success he expanded, but remained until his death in this small side street dedicated to artists.

Ariane Coulondre

Starting from this idea of the studio, the wellspring of Brancusi’s work, curator Ariane Coulondre has achieved the staging of an absolutely exceptional exhibition, as informative as it is beautiful, containing nearly 400 pieces including 150 sculptures by the master of streamlined forms. Nowhere else but the Centre Pompidou – the institution that inherited the contents of Brancusi’s studio – could take on such an operation. It’s also not due to travel elsewhere. (See here a report about the last Brancusi exhibition in Romania).

Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp

Except for when his friend Marcel Duchamp would sell his sculptures across the Atlantic, transforming into a dealer for a time, Brancusi refused to exhibit his works outside of his ecosystem. “When he would grudgingly and out of necessity sell one of his sculptures to a collector, he would make a mould of it beforehand in plaster in order to replace it within the great sequence of the studio, which he liked to be constantly renewing,” explains the curator of the exhibition.

Dancing works

The studio was also his living space – he slept until the end on the studio’s mezzanine – and space for entertaining. See the wonderful little silent film he made in which the daughter of an American collector, Florence Meyer, traces a few graceful movements among the sculptures. Brancusi also made his works dance. He arranged them on mirrored surfaces that could be very slowly moved with ball bearings and later a motor, as is the case at the Centre Pompidou of “Léda” from 1926. The turning disc allows us to appreciate the different aspects of the form, according to the viewpoint.

His artisan side

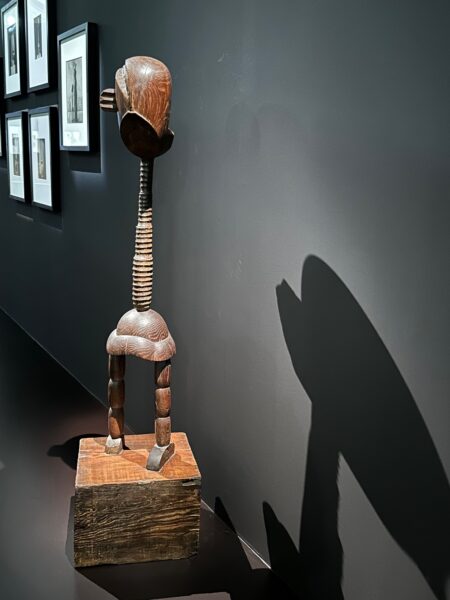

His works may be pared-back but his personality was complex. He certainly had a rustic, artisan side to him, and he perfectly mastered the manual work involved in his sculptures. The curators at the Guggenheim in New York x-rayed one of their Brancusi works, “Petite fille française”, a little-known sculpture clearly inspired by African art carved from wood from around 1914. They then realized it had been carved from a single block, which required a certain level of dexterity.

Promotor of his own myth

When he created bronzes the artist took it upon himself to create the glossy and shining patina. But Brancusi was not a creator eternally barricaded in his studio. He was also the skilful promotor of his own myth. In his space he was the one who photographed and developed images of his works. The Musée national d’art moderne has inherited no less than 1600 of his photos. Man Ray provided some advice on techniques in the discipline.

Filming himself

He was also the one who filmed himself working. Social or business visits were organized according to the light in the space. He knew how to manage its effects by painting certain walls to make the forms stand out or by putting up screens that concealed the artworks.

The same theme again and again

His body of work was not huge but, as the exhibition demonstrates very well, he would infinitely work and rework each theme, animated by variations, over many years. Between 1909 and 1918 for example he sculpted around fifteen “Muses endormies”, a head reduced to its simplest expression. Egglike, with a nose, eyes closed and hair slicked back.

Oiseaux dans l’espace

Similarly between 1919 and 1947 he created around thirty “Oiseaux” in the space, this slender form with a thin base resembling birds’ feet. It challenges the rules of equilibrium. “Brancusi would say he didn’t want to sculpt a bird but rather its flight,” points out Ariane Coulondre. At the Centre Pompidou this major series is the subject of a majestic installation opposite a wide window overlooking the rooftops of Paris.

Before Arp, Serra, Koons

While visiting the exhibition it’s possible to measure the extent of the artist’s influence on what came next in art history. Clearly the modern artist Jean Arp looked at the smooth, quasi-abstract forms of his predecessor. The American sculpture who has just passed away (see the homage to the sculptor here), Richard Serra, spoke of his formative stay in Paris in the mid-1960s, during which he repeatedly visited Brancusi’s studio, then at the Musée d’art moderne. We also see the influence he had on the shiny metallic sculptures of American artist Jeff Koons (See the last interview of the artist here). This is a fitting return to history. Because Brancusi himself decisively took inspiration from one of his elders.

Rodin, the master

In 1907, for scarcely three months, he was one of the “hands” at Rodin’s atelier. His most famous line, “Nothing grows well in the shade of a big tree,” justifies his swift departure from Rodin’s studio. But his thoughts about the importance of the creator of the Thinker are richer than that: “Since Michelangelo sculptors have wanted to make the grandiose. They have only succeeded in making the grandiloquent (…) Rodin came and changed everything (…) His Balzac remains the incontestable starting point for modern sculpture.”

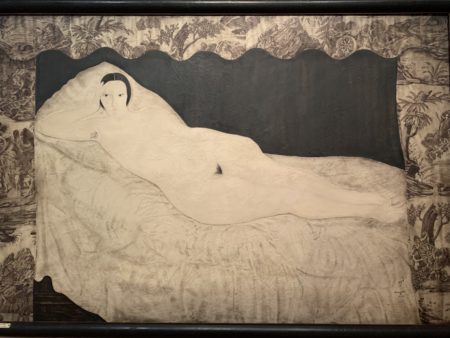

The head without the neck

With Rodin the young Romanian learned how to use fragments of the body. In 1878 Rodin, to give the necessary strength to his “Homme qui marche”, cut off the head and arms. Brancusi, when he wanted to make a portrait, decided to only show the head. Even the neck is removed. However contrary to his elder, he wanted to create a smooth kind of sculpture in which the trace of the artist’s hand cannot be seen.

The studio has disappeared twice

Since 23 September 2023 Brancusi’s studio, housed in a small building designed by Renzo Piano opposite the Centre Pompidou, has been definitively closed. It has been there since 1997. Since the original studio in the Impasse Ronsin was destroyed in the 1970s, afterwards the land was sold to the neighbouring Necker hospital. Administration reduced one of the loftiest places in the history of modern art to pulp, in order to make a small evacuation route for the deceased from the hospital.

Brancusi’s Kingdom

This sinister fate produces a paradox: the famous studio has now disappeared twice. Return in 2030 for the reopening of the Centre Pompidou (it will be closing progressively from the autumn of 2024) to find out whether “Brancusi’s Kingdom” will be brought back to life.

Until 1 July. https://www.centrepompidou.fr/fr

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.