The other’s neckline dips low to reveal a milky-white neck, her head tilted back with eyes half closed as though under the effects of an ecstasy drug.

A naked young man sitting on an animal skin, wild with happiness, smiles out at the viewer.

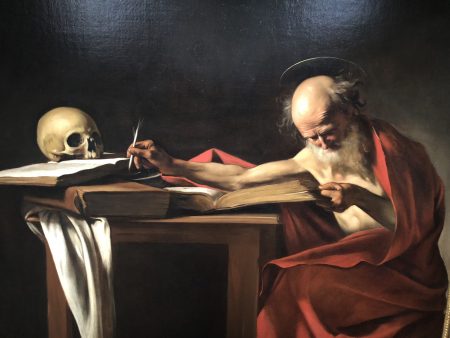

And a scrawny old man wrapped in a red cloak reads in a masterful chiaroscuro.

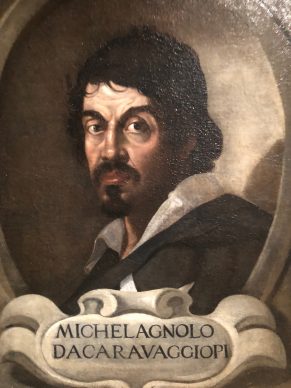

These are the figures that populate the world of Caravaggio (1571-1610) and they are called Judith, Magdalene, John the Baptist and Jerome. Here the label of “saint” is a detachable one, for Caravaggio was certainly the most secular of the religious painters.

But above all the Italian was a creature of extremes, for he knew how to combine his frenzy with a certain level of mastery that is expressed through every pore of his paintings.

And if he is one of the old masters who engenders the most enthusiasm in the contemporary period, it’s because he went beyond the conventions and codifications of old master painting and those that appealed to the taste of the church. Even though his work has elements of a metaphysical nature.

For the artist-troublemaker who would even go on to commit a crime, the biblical heroes took on the appearance of his models of choice, a prostitute, his friends, his lover (?) but each one presented in a most sublime way.

According to the respected Italian art historian Francesca Cappelletti, Caravaggio only painted between 50 and 56 works if we limit ourselves to strict attributions.

At the Musée Jacquemart-André in Paris she has chosen to only display works from his Roman period, while he was finding his pictorial personality in the papal capital.

The exhibition features 10 works by Caravaggio, which is a great feat in itself, to which are added 24 works made by his contemporaries and rivals, which serve to contextualize the artist’s work. Francesca Cappelletti explains the challenges involved in staging such an exhibition:

So we find a piece by Annibale Carracci (1560-1609), the star in Rome at the time, and another by Giovanni Baglione (around 1573-1644), the rival whom he mocked in poems resulting in a trial in 1603.

Where Caravaggio truly excelled was in his depiction of solitary figures.

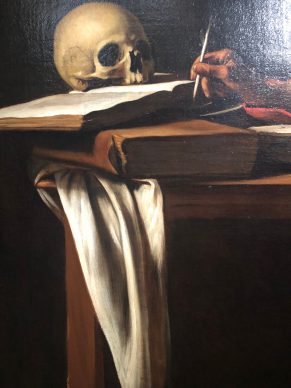

His “Saint Jerome in His Study” from 1605-1606 is staggering in its humility. The polychrome tones of this painting, mainly in shades of brown, and the pure lines of the composition all contribute on canvas.

The height of ecstasy is reached in the final room where there are two women, also with expressions of ecstasy.

Magdalene has a dazed and wild-eyed look that resonates with pleasure.

The lower part of the painting is red. The middle is white, the top is a dark brown. Two versions of “Magdalene in Ecstasy” are presented side by side, one of which was rediscovered almost three years ago and is considered to be of a better quality than the other and the “Klein Magdalena”, named after its owner.

We know that Caravaggio could repeat himself. Are both works valid? Francesca Cappelletti attributes both to Caravaggio. Art historians will no doubt continue to ponder this “ecstatic” case. As for visitors to the gallery, they can only be confused by this double image of quasi-Warholian pleasure (albeit more beautiful).

Until 28 January. Paris. www.musee-jacquemart-Andre.com

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.