Until the June 18 opening of an exceptional confrontation between Much and one of American contemporary art’s kings, Jasper Johns (born 1930), who very frequently used motifs that can be found in the Norwegian artist’s paintings, the museum is presenting a fruitful parallel between Robert Mapplethorpe, the death-obsessed American photographer, and the father of The Scream. “Never did James Mapplethorpe make any reference to Munch,” stresses museum director Jon-Ove Steihaug, who curated the exhibition. “This, here, is rather in the realm of experimentation.”

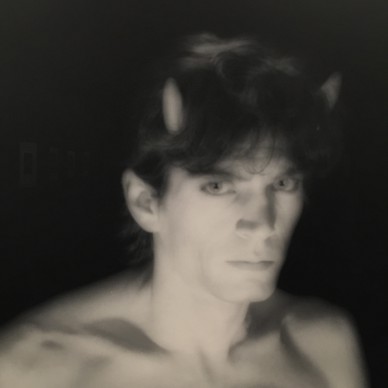

Out of this adventurous presentation, Munch certainly comes out the clear winner, thanks to his Expressionist canvases, ceaseless searching and sumptuous colors exploding in viewers’ eyes. Still, the two artists have a few things in common. Munch commonly made use of photography, which served as a base to prepare his pictorial work. One of his favorite subjects was himself, long before the era of selfies. Of course, the American artist was very much into self-portraiture, of a more polished and accomplished kind. Both commonly worked around the theme of death. Across from the famous self-portrait Mapplethorpe made in his last days as he chronicled his physical dilapidation accompanied by a cane with a skull-shaped knob (he died of AIDS at age 42) hangs a black-and-white print representing the face of the Norwegian painter under which the skeleton of an arm has been placed. Vanity of Vanities…

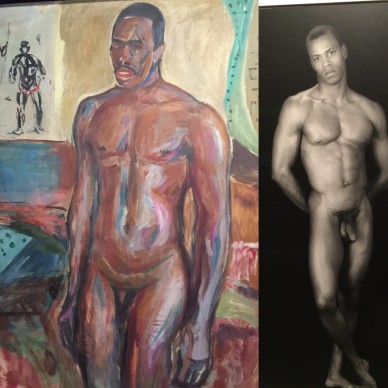

Munch’s biography shows he was rather drawn to the feminine sex, even if all his relationships ended in fiasco. And yet, a giant phallic shape, often presented under the guise of a giant shadow, haunts a great number of his compositions, such as Puberty, the nude portrait of a young woman, and Summer Night, where the moon’s reflection on water also takes on this characteristic outline.

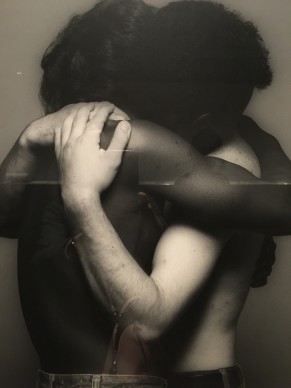

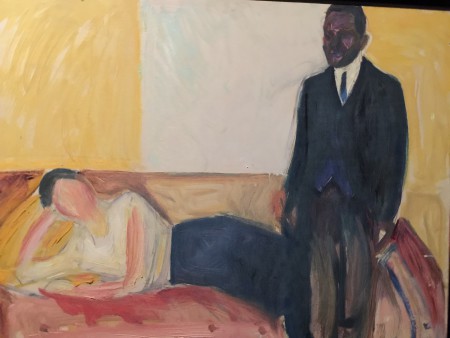

Mapplethorpe, who had a very rich sexual life, commonly portrayed the men who’d spent the night with him the next morning. He also made their sexual organ an art subject in its own right. Finally, in the very blond early 20th-century Oslo, a beautiful black man who worked in a circus would sometimes stop in town. His name was Sultan Abdul Karim, and Munch portrays him but without giving him an exotic image. Dressed or undressed but at rest, this man bears a strange likeness to the objects of fascination who will come to haunt the last part of Robert Mapplethorpe’s artistic and sentimental life.

This imaginary dialogue between two top artists in their own categories deserve credit for helping us understand to what extent Edvard Munch opened the door to contemporary artists. While his use of decorative motifs in the background of his compositions recalls Matisse and his representations of bathers may perhaps even recall Cézanne, his female nudes herald Lucian Freud and his couples covered in sprays of colored lines announce the German genius Sigmar Polke. You should rediscover Edvard Munch. Mapplethorpe serves as an excellent pretext for doing so.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.