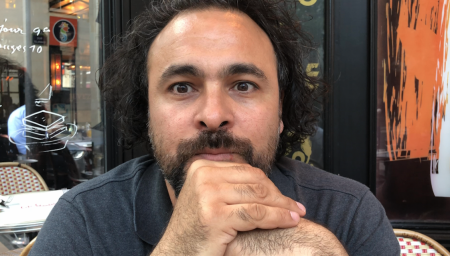

On the big international art show circuit, Kader Attia (born in 1970) is everywhere.

He was exhibited at the penultimate Documenta in Kassel in 2012. One of his large-scale works was exhibited as part of the permanent collection at the opening of the new building at the Tate Modern in 2016.

He had a large-scale installation at the most recent Venice Biennale. He will be included in the programme of Manifesta (the roving European biennial) from 15 June and from the same date at the Miro foundation in Barcelona, and also from 7 September at the Korean biennale in Gwangju.

But for this French-Algerian artist who lives in Berlin the current focus is primarily a homecoming of sorts, in the Parisian banlieue, for he is being exhibited at the MAC VAL museum in Vitry.

He grew up within the then happy cultural mix of the banlieue in the north of Paris, at Garges-lès-Gonesse.

His father, who had emigrated from Algeria, worked in construction and he reminisces happily about those years when he was close to his Jewish friends, to the point of exclaiming: “Ha! Mrs Abécassis and her Shabbath couscous!”.

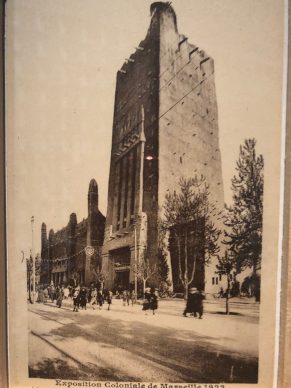

His work, which is political and conceptual and comprises films and installations, runs contrary to all commonplaces relating to these areas on the margins of metropoles and these formerly colonized populations.

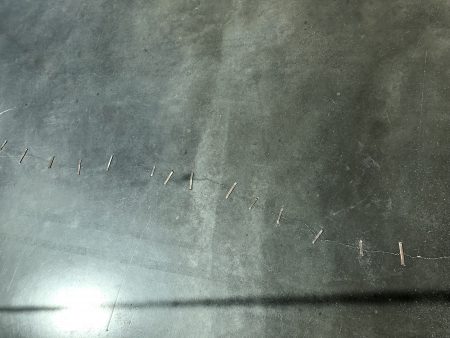

One of his favourite themes, therefore, is that of repair. He says: “in traditional cultures, damaged objects were visibly repaired. Today we want to give the impression that the passage of time mustn’t leave any trace, either on the body or on objects. It’s a serious problem in our societies.” Quoting the American writer Cormac McCarthy, he adds: “Scars remind us that our past is real”.

Thus Kader is a collector of scars.

He talks about the notion of repair:

At the entrance to the exhibition, the more observant visitors will notice that he has placed staples in the concrete floor to secure the cracks that have appeared over time.

Kader says he is interested in “the ambivalence of things”. One of the most striking installations is a cement mixer (symbolizing his father) in which 50 kilos of cloves are churning (reminiscent of the aromas from the food prepared by his mother).

He has also embedded traditional breads within the walls of the museum.

It’s as though these flatbreads have become a sharp-edged weapon. The weapon takes the form of the knowledge drawn from his roots. “France is also what we call the banlieues, with its architecture, its smells, its different cuisines,” he concludes, having called his exhibition: “roots also grow in concrete”.

Until 16 September. www.macval.fr.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.