His name sounds like the first sparks of an eruption: Olafur Eliasson. That’s not surprising, as the Berlin-based Danish artist’s mother and father both come from the most volcanic country imaginable: Iceland. And you can’t help thinking that his oversize works, which submerge the viewer’s sense, these otherworldly atmospheres—Eliasson works with light, shadow, reflection and the elements—come from his contemplation, from the youngest age, of these big, almost lunar Icelandic spaces that have the power of making you lyrical. “Iceland is like a contemplative Asian garden with suddenly muddy spaces, “ he says. “A very moving combination of beauty and ugliness. A land that is both known and unknown. I feel a strong sense of belonging in that country,” he confesses. “I feel at home there.”

But today, Eliasson is moving through another type of landscape: his Berlin atelier in the trendy Mitte district, spread on two floors of an immense industrial building, a former brewery repurposed into an incubator of fantastical projects—extremely spacious and filled with beautiful, trendy-looking young people who are communicating, reading and thinking. Everywhere are leather couches, bookshelves and models for clever geometric constructions. The technical floor is a mini Cap Canaveral where the forthcoming sophisticated illusions Olafur has been setting up are tested. For those not yet in the know, we are in the lair of one of the planet’s most prominent artists. His next stop is the Fondation Louis Vuitton, where he is organizing a big “show” that will occupy the building’s entire first floor.

Olafur is beginning to talk about Paris, but he is interrupted by a young girl. “This is my daughter,” he says, listening with affection to what this little face, about 10 years old, is saying. Her hair is messy, the look in her eyes bright. She’s as energetic in her making conversation as her father is measured in his speech. She swirls around him. She’s made a fuchsia-colored cream cake that she wants him to taste right away. Another kind of experimentation. She comes back a few minutes later, on roller skates—you have to admit the spaces here lend themselves particularly well to this type of locomotion—and then comes back again. Until the time when her father eventually entrusts her with color markers. The interview may proceed.

Olafur Eliasson says he is particularly attentive to Paris because it is the place where his first large-scale exhibition took place. “It was in 2002, at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris,” he says. However, it was the next year in London that he reached the pinnacle of his reputation, with a spectacular installation in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. The idea may seem simple but the impact was radiant: In this monumental closed space, he created something that looked like a large sun, whose effect was accentuated by mirrors and artificial mist. The entire world came to get warm under his rays of illusion. As if on a quest for a mystical light, the Tate’s visitors were blinded. They even often lied down on the slope at the museum’s entrance in order to capture his golden rays.

In 2005, Olafur Eliasson came back to Paris and did exactly what was not expected of him. When Vuitton asked him to create a work for its flagship boutique on the Champs Elysées, the artist conceived a piece—still “visible” today—that plays with the opposite of the blinding effect: total darkness. To reach the luxury firm’s cultural area, you have to use a completely dark, soundproofed elevator. An elevator man keeps you company along the dark journey up five floors and reassures you about the ability to turn the light on, should it become necessary. Eliasson imagined the void, darkness and silence in motion. This is the point at which you ask how the people who commissioned him reacted. He always responds slowly, but this time reveals a slight grin at the corner of his mouth: “Yves Carcelle[1] was the person I dealt with. He knew I couldn’t be bothered with pragmatic problems. He wanted a real work, not something decorative,” the artist says. “Taking an elevator in the dark amounts to losing control for a short while. Letting your unconscious go. The shop is full of decorations. What I was proposing was the opposite,” he continues. “To some extent, by making this proposition, I unburdened their unconscious. And anyway, when you go into a boutique, when you are willing to consume, it’s a way for you to feel both different and safe. With the elevator I was proposing a different way of feeling safe.”

Olafur is a very ambitious man. “In fact, the elevator would have had to be installed in the Eiffel Tower for it to reach its full effect.” Then the artist goes off on a tangent: “The Eiffel Tower is the quintessential great utopian project. The reason it succeeded in coming to life is because it is a real work of art.”

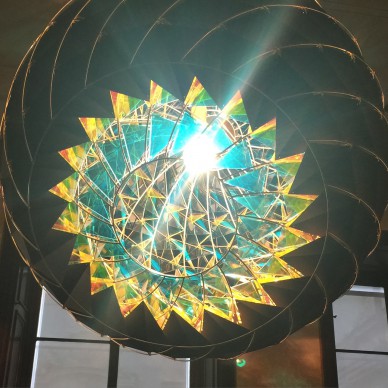

The following year, 2006, Yves Carcelle asked Eliasson to do something for the windows of Vuitton shops across the world at Christmastime. This time around, the Danish artist returned to a radiant work. “I imagined a lamp-sculpture with a mirror system,” he says, “a process that diffused solar energy with a reflection on the street. A way to show that the separation between interior and exterior can be blurry. It’s just a matter of personal awareness.”

Here too, Olafur Eliasson proved himself to be demanding. “I’d said that I didn’t want the works to be associated to a function,” he notes. Meaning: no bags next to Eliasson’s work in the shop window. “Yves Carcelle asked me whether I was aware of the fact that the shop windows were planned for December, that’s to say, Christmas,” the artist recalls. “I said that there was no hurry; we could do them in January.” By way of justification, he adds: “You don’t create half a work of art. You don’t do half a Cézanne. They [Vuitton] were visionaries in their idea of using artists. It’s important the artists find themselves in the proper conditions to create art.”

So the project remained on the table and seems to have satisfied everyone. “I was deeply happy. It was a success, and Vuitton played the game until the end,” Eliasson notes. “I was fascinated by the fact that the operation concerned all boutiques around the world. In all the cities and in all the best locations in these cities. Of course, in theory, I knew it,” he continues, “ but when I got to really producing it, I thought this operation consisted in a revolution, in the literal sense of the word—a complete journey around the world that was beginning with Australia.”

Eliasson recounts his global performances, and the most natural question in the world comes to mind: “How does one go from the status of a ‘normal” artist who draws, paints or sculpts to a practitioner who just wants to create atmospheres and sensations?” This is what Eliasson has to say: “In fact, when I began as an artist, I was interested in psychology and phenomenology. I tried to dematerialize what was an artwork. I was interested in poetry above all, and in Californian artists who were already playing with space and light, like James Turrell and Robert Irwin. I was obsessed with the contemplative sciences, spirituality, religion. Today, I am more interest in sociology, like the works of Frenchman Bruno Latour. In fact, he wrote a text for the exhibition catalogue at the Foundation Vuitton.”

At last! Eliasson finally agrees to broach the subject of his exhibition at the Fondation Vuitton this December. Naturally, the project occupies all his thoughts. His army of engineers, architects and sundry specialists is working on this operation at this very moment, but he himself would rather not talk about it. Oliasson is not one to count his chickens…

Still, he says that the project was decided even before construction on the Frank Gehry-designed building in the Bois de Boulogne was over. “Suzanne Pagé [the foundation’s artistic director] asked me to come visit her in Paris. Construction on the building had barely begun,” Eliasson recalls. “I met with Bernard Arnault and Frank Gehry, who wanted to know if I accepted to produce the first exhibition. Of course, I was happy, because it’s not so easy to work with me. The project consists in taking this very peculiar space into account. Gehry managed to give the impression that you are in a vessel. My wish was to make works in an ambiguous space that gives the impression of being between exterior and interior. My idea: to create the illusion that you are walking toward the horizon through a kaleidoscope effect. More generally, all the works that presented in Paris at the Foundation Vuitton are new.”

Eliasson continues his description of the idea that governed his project: “The concept I presented to Bernard Arnault and Suzanne Pagé is simple, as it usually is in the beginning: In this first-floor space, which is nearly 50 meters [164 feet] long, I drew two new spaces, using a circle and a triangle. A lighted part represents the question of consciousness; the dark part embodies our subconscious, all the things that we haven’t verbalized yet. Between the two spaces, I conceived a connection. Its shape is that of the infinity sign.” It is difficult to imagine this exhibition concretely, but by coming across installations and models here and there around the workshop, you understand that, as usual, it will be about atmospheres and effects of perception. Here is a shadow theater with a gigantic magnifying system reflecting what is outside; there, a convex floor giving the feeling that you are walking on the globe’s surface, as in a drawing by Saint-Exupéry: “Like in the Little Prince,” Olafur notes. At the time of writing, the project’s various components are not defined. Still, the artist declares, with the provocateur’s glint in his eye: “I think the spaces will be empty.” Basically, Olafur Eliasson is playing with the viewer’s sensibility to create object-free spaces that give birth to emotions. Just as, in older days, an eloquent painting was likely to evoke a feeling.

[1] Now deceased, Carcelle was Vuitton’s charismatic former president.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.