Sigmar Polke (1941-2010) is true a giant of painting from the second half of the 20th century but has yet to receive the full credit he deserves.

This is especially apparent when compared with his fellow countryman Gerhard Richter (born 1932) who can properly be considered his legitimate rival in terms of timeline and importance .

Richter’s work currently fetches record sums on the market and his reputation is unrivalled while Polke gets relatively less attention. It’s true that with the multinational gallery Zwirner now representing Polke’s estate, this should have a considerable impact on his market value. Furthermore, his 2014 retrospectives at Moma in New York and the Tate in London also greatly enhanced the historical significance of his oeuvre.

But while these major exhibitions left the artist’s virtuosity beyond any doubt, they failed to give a coherent account of his work. They even managed to give the viewer the impression that the artist himself was incoherent. Opening at the end of this week at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice, owned by the French collector and businessman Francois Pinault, will be a solo exhibition counting 90 works (16 belonging to Pinault) in which nothing has been left to chance. This is in large part thanks to the work of independent Italian curator Elena Geuna and Grenoble Museum director Guy Tosatto, who not only knew the artist well but also included him in three exhibitions while he was still alive. Tosatto offers the beginnings of an explanation about why recognition came belatedly to the artist. ‘Polke didn’t chase after exhibition projects. He didn’t answer the telephone. He didn’t give interviews. He didn’t leave behind writings. He wanted to be free of all commitments.’

Elena Geuna outlines her ambitions for this exhibition in the following terms:

As for Michael Trier of the Polke Estate who knew the artist well, here he describes his temperament:

The exhibition succeeds in clearly re-establishing the chronology of Polke’s creative journey while at the same time exploring his various strands of research.

In the 1960s Polke forged a deep friendship with Richter. The two young men from East Germany studied together in Düsseldorf. The exhibition catalogue provides a quote from the latter: ‘Everything seemed stupid to us and we refused to take part. That was the basis for our understanding.’ Their earliest works in this period were Pop Art with a German touch. In an ironic twist, and in reaction to the socialist aesthetic, they named it ‘capitalist realism’.

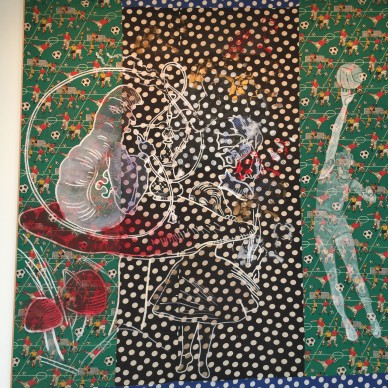

On a technical level, Polke magnified his subjects, which he pulled from articles and adverts, using a multitude of raster dots. It’s a technique that he would employ throughout his career.

In the 1970s, ‘Polke drifted in a psychedelic direction and I in a classical direction,’ said Richter in 2001.

‘He looked for journeys into the imagination, without a net,’ explains Guy Tosatto, alluding to the artist’s use of drugs. In his painting he began to experiment with translucent canvases, which replaced the traditional canvas and enabled him to generate light effects. He also used printed fabric, which served as the background for his new compositions. The images are copied, traced, telescoped.

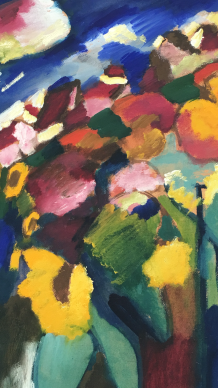

In the 1980s Polke immersed himself in a strain of universal mysticism, which he concocted in his own distinctive way with alchemical sigils and rituals from remote lands, which he encountered on his extended travels between Australia and Malaysia. He played with ancient pigments, chemical experimentations, legends and beliefs. Polke the magus made the colours and themes explode. The messages are encrypted. One has to leave behind the guidelines of customary readings to glimpse this German artist’s messages. In some ways you’re led to think of the hieroglyphs of another German currently showing at the Pompidou Centre, Paul Klee.

In 1986 Polke was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale and made something of a return to his aesthetic mix of Pop and politics. At the entrance to the German pavilion he placed a painting of a pig dressed as a policeman, that we get to see once again in the stairs of the Palazzo Grassi .

Abstract and figurative, serigraphs and printed canvases, transparency and opacity, pure and impure colours. Polke is beyond classification. It’s a body of work that is ‘mystical, ironic, serious and grating at the same time,’ adds Martin Bethenod, the Palazzo Grassi director.

Today Sigmar Polke is the link in the history of art between a modernist like Picabia and the trashy, post-pop actual painting of Californian artists like Friedrich Kunath or Josh Smith.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.