The opening of the Venice Biennale is a non-virtual social network. More precisely, the Venice Biennale resembles a kind of Olympics Games for Contemporary Art. It’s the place where, every other year, the contemporary art world and the contemporary art market meet up to see what could be described as the world’s most copious supply of current art. But above all, the Biennale is the exact incarnation of an avalanche of supply, where you’ll miss a great many things that, in other people’s eyes, were the most awesome.

As the young Internet set would say: “I get FOMO in Venice.” For a simple reason: the Biennale consists of 136 artists exhibited over the 110,000 square feet of the official Biennale, plus 89 participating countries exhibiting in their pavilions, plus 44 side events, plus a veritable orgy of exhibitions off the beaten track. Everywhere in the city, in rotting palaces, in sumptuous residences, but first and foremost at the Arsenale and Giardini, you trudge through exhibitions and pavilions, going from one discovery to what may be a non-discovery.

This year, the curator for the Biennale’s two international pavilions is Okwui Enwezor, born in 1963, who’s best known as the creative director of the 1998 Documenta in Kassel. What word best describes what he’s offering? Paltry. No surprises, or a very few. Nothing strong, or just a few things. It’s like intellectual chatter serving to mask theoretical poverty, with the visual aspect of these offerings being just as poor.

This year, Okwui Enwezor settled on Carl Marx’s Das Kapital as a war horse. And why not? This could have been most excellently provocative, except that Enwezor’s appeal to a common conscience is presented with a mad poverty of ideas, which can only lead to disappointment. Throughout the day, at the center of the Giardini pavilions, performances are given, all of them sharing a coda: a reading of Das Kapital orchestrated by British artist Isaac Julien. The press material explains: “Here Das Kapital will serve as a sort of oratorio, which will be read live, throughout the Biennale’s seven-month run.” When you know that Isaac Julien, right here in Venice, is presenting new work commissioned by automobile concern Rolls Royce, you understand that, for him, Karl Marx’s bible is a coquettish accessory, not a moral one—just like the cross Madonna wore around her neck back in her younger days. It’s certainly okay to look for morality in contemporary society, but it has to be true morality, not some flirtation with aesthetically rebellious posturing. In his declaration of intent, as a kind of ultimate coquettishness and as if he wasn’t aware that no one reads anymore, let alone reads Das Kapital, Enwezor writes: “Of course we have all read, and do read Das Kapital. For almost a century we have been able to read it every day, transparently, in the drama and dream of our history.” An art critic told me in confidence that this intellectual posturing reminded him of the paradox of Che Gevara’s Rolex, which became a cult object.

All this to say, in conclusion, that the works on offer at the Arsenale are mediocre; they’re somewhat better in the Giardini, though still quite disappointing.

So let’s talk about the national pavilions.

France is being represented by Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, born in 1961, who is mostly known for working with sound. Here he is presenting a poetic and contemplative pavilion animated by actual pins stuck in tree roots, which are moving through space as if by magic. You can settle on moss-covered bleachers and listen to these foreign sounds that, according to the artist, reflect the electricity being emitted by the trees. Outside, other pins are also dancing in the Giardini. The space has been opened. Emma Lavigne, the curator for the pavilion, sees in this work an allegory about uprooting.

The best pavilion by far is that of Romanian Adrian Ghenie (born 1977). Ghenie paints from a maelstrom of violence, movement, color and impregnation with art history. Without a doubt, he’s a man with a tremendous amount of talent. This mini-retrospective is a demonstration of the fact that this painter belongs in the continuum of great painting. He is not a discovery, and the art market is in fact showing excitement about his oeuvre.

Provocative and excellent as it should be, the British pavilion steers clear of received ideas; it’s occupied by Sarah Lucas (born 1962). Hats off to British authorities for allowing their country to be represented by a series of installations verging on the pornographic. Lucas, a historic member of the Young British Artists, speaks violently about women’s roles, their sexuality, and the role of the housewife. She runs counter to the sexy, stereotypical representations of the glamorous woman. Her stretched-out phalluses in loud yellow, her contorted marionettes, the smoke coming out of her women’s buttocks make a mockery of the image of the fiftyish housewife and her husband. A descendent of Louise Bourgeois with a pinch of Annette Messager.

The Giardini’s entrance is marked by Oscar Murillo (born 1986), an art world star who remains promising nonetheless. A suite of immense black canvases like flags at half-mast, which he treats (and mistreats) like tarps—painting on canvas ain’t what it used to be—stresses the world’s tendency to go bad.

In the international pavilions, you might wonder why super well-known images, icons of capitalism from the German photographer Andreas Gursky, are being presented, but you will pay tribute to the impressive series by the always morbid but excellent South African artist Marlene Dumas (soon to be exhibited at the Beyeler Foundation), of 36 painted skulls.

At the Biennale, filmmaker and visual artist Steve McQueen is showing an elegiac short in memory of a sculptural young man he’d met in Granada Islands, whom he’d filmed almost by accident and who was since been shot by drug traffickers.

Christian Boltanski has made a short and very poetic film about small bells he installs in the wind, which ring like the forgotten souls that resurface in our memory. The real bells were installed in Paris’s Jardin des Tuileries during last fall’s FIAC.

An entire room is devoted to Japanese artist Tetsuya Ishida (1973–2005), a realist- or even Surrealist-type painter, who represented the common man’s alienation in contemporary Japanese society.

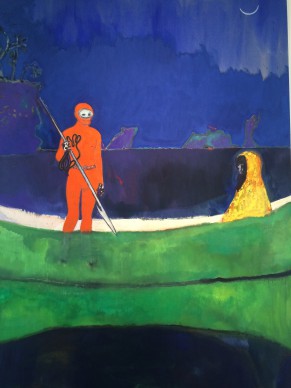

The excellent British painter Peter Doig (born 1959) at Palazzo Tito is clearly a sure value at the moment. His universe is black, but Doig now operates according to a fascinating technique: he’s painting within a painting, which creates pictorial complexity married with a mastery of color.

If social morality is the point, then you should visit the excellent Mario Merz (1925–2003) exhibition at the Gallerie Dell’Academia: Merz wasn’t posturing or faking. This representative of what is called the Arte Povera movement created installations out of nothing—bread, metal, neon, stones—which created a universe that is both chaotic and harmonious. Many are the followers of today who are attempting, in vain, to reproduce his recipe. As Saint Petersburg Museum curator Ollesya Turkina said upon seeing Doig’s works: “In the end you can’t cheat with art.”

In the sublime Venetian light, you should also go to international modern art gallery Ca’Pesaro and see the exhibition devoted to American painter Cy Twombly. Thanks to the large chronological spectrum on view, you will better understand the combination of gesture and intellect in Twombly’s works, which resulted in an oeuvre that literally exploded with color and pleasure toward the end of his life.

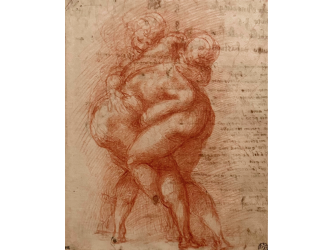

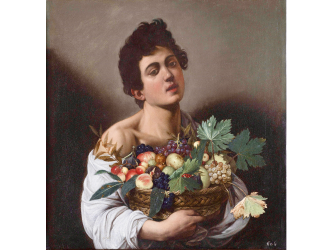

Another mention should certainly go to the most beautiful exhibition the Punta de la Dogana has ever hosted thus far, organized by Danh Vo, an artist of Danish and Vietnamese origin. In this space, the artist has reconstituted his pictorial universe from memories, fragments, wounds and influences ranging from Bellini to Bertrand Lavier.

After this cascade of visits, you’ll need time for a rest, as did this Venetian delivery man, who seized to occasion to sun himself on his little boat. O sole mio!

After this cascade of visits, you’ll need time for a rest, as did this Venetian delivery man, who seized to occasion to sun himself on his little boat. O sole mio!

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.