A good artist is a person who can create a unique universe. In Venice this year, at the Pinault Foundation’s space (1) at Punta Della Dogana, Danh Vo goes further as he imagines, along with curator Caroline Bourgeois, an artistic microclimate consisting of works that, in their overwhelming majority, are not his own. This ancient customs house’s red-brick walls bear the traces of its former use and make an extraordinary jewel box for a show encompassing some 50 artists and several centuries. Danh Vo is interested in history and art history “so as to be free,” he says. “Knowing history keeps you from being controlled, from being manipulated by others.” His sensibility expresses itself in his attachment to symbolic objects that correspond to important moments in his biography. “I went to church every Sunday until age 18. I think I’ve been traumatized by Catholicism. But when you’re a Catholic, you’re particularly sensitive to objects.”

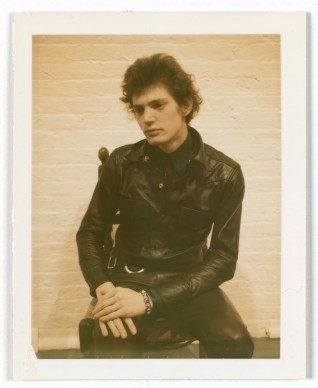

The revelation of his calling as an artist occurred the day he first encountered the work of one of 1980s American art’s mythical artists, Felix Gonzales-Torres, who died of AIDS at 39. At the Palazzo Grassi, we come across Gonzales-Torres’s famous red curtain, which symbolizes drops of blood as well as the disease itself. Danh Vo has also made room for another artist from the AIDS years, American photographer Peter Hujar (1934–1987), who has been forgotten but to whom Danh Vo wants to give his due. In New York at the time, Hujar made particularly expressive portraits of dogs as well as highly sexual portraits of men.

Fragmented, broken-up and superimposed objects are found everywhere in Danh Vo’s narrative. Carnation Milk is a brand of American condensed milk that the artist drank throughout his childhood. He’s salvaged a container of this affect-laden beverage, in which he’s placed a bust of the Christ cut to fit the receptacle. It’s Carnation and incarnation; childhood and Christianity.

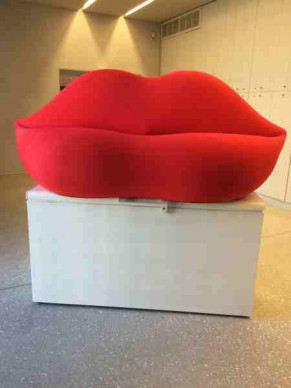

In one of his own installations, the artist has also recomposed a set of appliances the Danish State gave his grandmother upon her arrival in the country: a fridge, a TV, a washing machine and an enormous crucifix, a symbol of her conversion. This set of relics from immigration is presented in a form inherited from Marcel Duchamp’s Ready Made’s. At the entrance to the exhibition, as a form of welcome and a bit of a wink, Danh Vo has chosen to place a work by French Conceptual artist Bertrand Lavier, who himself also uses superimposition. One on top of the other, Lavier offers two standards of domestic life: a sofa designed by Salvador Dali in the shape of giant red lips and an enormous freezer. A summary of the housewife’s charms. And so visitors walk around between the traces of various narratives, which are arranged without regard to chronological order but share an affinity with the artist’s personal story. Danh Vo is particularly sensitive to the issues of war and the damages left by invaders. For instance, a 19th-century photograph shows a Pekinese dog—the breed had until then been the Chinese emperor’s exclusive property—that had been brought back to the Queen of England after the 1860 siege of Peking’s Summer Palace. The dog was christened Looty, from the English word “loot.” In several rooms, paintings and pages of illuminated manuscripts from Venetian collections are shown as fragments. Sales of these pieces of paintings reportedly started flourishing after Napoleon’s passage in Italy.

“No artist comes from nowhere,” concludes Danh Vo, who is also representing Denmark at the Venice Biennale this year. “Personally, I come from those artists,” adds the globalized art-maker, with his usual wide smile.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.