This is the story of a man who in 1969 opened a store selling jeans and ended up with a ready-to-wear empire spanning 3,100 outlets across the globe.

It’s also the story of the simple son of a cabinet-maker from San Francisco who accumulated a collection of international contemporary art awash with Warhols, Richters, Calders and Kiefers aplenty.

An unadulterated product of Californian culture, Donald Fisher was the celebrated Gap founder, and valiant saviour of the Giants baseball team, who entrusted his cherished artworks to San Francisco’s modern art museum, SFMOMA.

On 29 April 2016, after a three-year refurbishment and enlargement, the museum was inaugurated to great fanfare with a magisterial exhibition featuring selections from the Fisher Collection, which includes 1,100 items.

Donald Fisher was born in 1928 and passed away on 27 September 2009, one day after the San Francisco Chronicle announced the agreement between the Fisher family and the museum.

Fisher was a great man on at least two separate counts and someone who epitomised the American dream.

At the age of 41, when he was still working as a real estate developer, he founded the Gap empire. By the time of his death he was worth $1.3 billion according to Forbes.

The second act in this great man’s life begins in 1979 when he bought his first piece of contemporary art.

‘Me and my brothers weren’t around any more so they needed a hobby,’ says his son Bob, with a smile.

The first item in the collection was by the American Pop Art star, Roy Lichtenstein.

Initially the Fisher couple – Don did everything jointly with his wife Doris – decorated the Gap offices with the contemporary works they bought, but in 1995, when their collection had reached a considerable size, they opened a large gallery at their new head office.

Bob recalls, ‘At the entrance to the Gap cafeteria my father put a monumental Claes Oldenburg sculpture of an apple eaten to the core. My father would repeat, ‘we’re in the creative business.’

At Gap everyone used to say ‘let’s meet at the ‘apple core’. When we donated the Oldenburg sculpture to SFMOMA we organised a small party. I have to say it felt more like a wake.’

Don and Doris made a pact from the outset: all the pieces had to be mutually agreed. Of course each of them had their own preferences. Doris for example had a natural affinity for the American abstract painter Agnes Martin and another abstract American artist Ellsworth Kelly who she spoke to every week up until Kelly’s death in 2015.

Don was fanatical about Alexander Calder, the sculptor who had close ties to the surrealists. Alexander Rower, president of the Calder Foundation, explains how he loved Calder’s fish works for no other reason than that his name was Fisher.

The Fishers were not intellectuals when it came to art. They loved both abstract and figurative work, from Andy Warhol’s bright and colourful Pop Art to the austere and dramatic canvases by Anselm Kiefer. They always bought art ‘on the basis of their visual enjoyment,’ emphasises Bob Fisher.

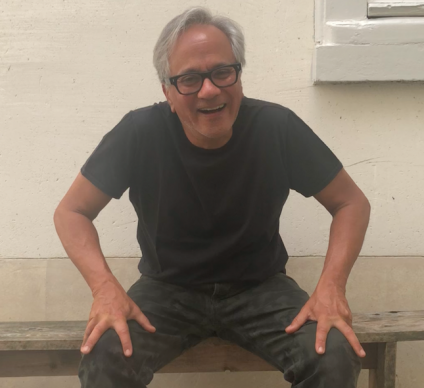

One of Don’s main partners in crime was the financier Charles Schwab, an important figure in San Francisco. At 78, his net worth is according to Forbes Magazine $6.5 billion. This silver-haired American gentleman came to honour the memory of his dear friend at the museum opening.

‘We mutually supported each other, in business and in art. In 1999 Don and I travelled to Japan to see a bank. The country was in a recession at the time. The establishment’s reserves contained an impressive range of art. Bacon, Giacometti, Klein, Jasper Johns…

After examining the collection, we had to decide who would take what,’ recalls the businessman. Even if millions of dollars were at stake, the mood remained good-natured between the two friends from San Francisco. ‘We selected ten works and allocated each of them a different number. We then put the numbers into a hat and drew lots.’ The outcome of this little lottery can partly be seen on the walls of SFMOMA today. Donald picked up, among other things, a large sculpture by Calder, a painting by Roy Lichtenstein and an abstract canvas by Frank Stella.

Charles Schwab also recalls how he persuaded Fisher not to open a museum in his own name in The Presidio in San Francisco as had previously been planned and announced in 2007, but instead let SFMOMA, expanded in this new scenario, accommodate the collection. ‘A family trust was set up for this purpose which lends the works to the museum for 100 years with a possible 25-year extension. They can’t transferred by the heirs,’ says Fisher’s friend. In addition, Doris Fisher has usufruct over a part of the pieces in her home.

Garry Garrels, the senior curator at SFMOMA who knew the Fishers since the ’90s knows perfectly how this colossal collection was put together: ‘Their aim was not to discover young artists. They wanted to understand what they were buying.

Naturally, more established artists already had a body of work behind them which made this easier.’ In 1988 they visited the renowned Documenta exhibition in Cassel where they discovered German painters like Gerhard Richter who was also given a retrospective at SFMOMA in 1989.

The Fisher collection contains 26 works by Richter in addition to paintings by Sigmar Polke and George Baselitz.

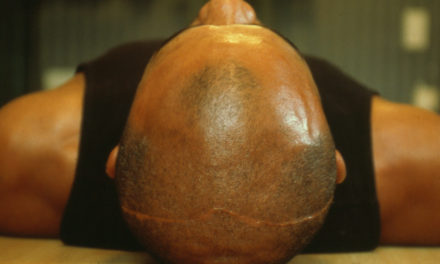

At the entrance to the rooms reserved for the Fisher Collection in the renovated SFMOMA building there is a figurative canvas painted in 1982 depicting two lit candles in the blurred style identifiable as Gerhard Richter’s. It’s neither the largest nor the most spectacular work by this German painter that the Gap founders owned, however it had a special meaning for them.

As the children Bob, Bill and John Fisher, explain in their introduction to the collection catalogue, these two candles symbolise their mother and father.

‘They bought this painting in 1989, drawn by its calm beauty and its intimate presence.

We gave it pride of place at home in a private room on the first floor where we could frequently see it. Mom and Dad were so attached to ‘Two Candles’ that when they left San Francisco each summer to escape the fog, they always made sure that the painting remained with them. Dad transported the painting himself, and hung it himself, summer after summer, even when he was well into his 70s. He got up on a ladder, took it off the wall, brought it downstairs and carefully placed it in the family car. In the house where they spent the summer there were two hooks waiting for the canvas that he hung himself (…) Dad is gone now. He lost his battle with cancer.’

Since the death of the Gap founder, Doris has almost completely stopped buying art, with the exception of a work by Ellsworth Kelly and another by one of their other favourite artists from South Africa, William Kentridge.

Of course, on the evening of the SFMOMA inauguration the Fisher offspring responded to the request for a homage to the family patriarch who occupied nearly the entire expanse of the museum.

But the following day, in the great Fisher family tradition, Bob organised a fishing trip with his friends in the San Francisco Bay.