Not retinal art

The 20th century will be defined as the period when art was completely called into question. It was Marcel Duchamp who proclaimed, very early on and contrary to what people had hitherto expected from artistic creation, that he didn’t want to produce “retinal art” – in other words he rejected art designed to seduce the eye.

Painting blind

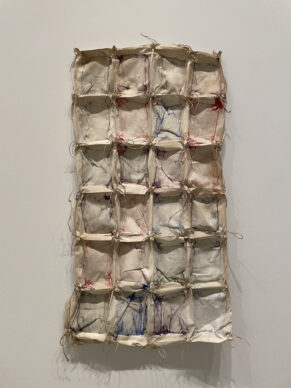

In his own way, the French artist of Hungarian origin Simon Hantai (1922-2008) followed his lead. He painted blind, with his hands as opposed to his eyes. It was in 1960 that Simon Hantai began to apply this bold gesture of “pliage”, or folding, as a general method for his creation.

His mother apron

In the 1970s he revealed that it was in observing the folds in his mother’s apron that he had the idea which would chart the course of his artistic life. Hantai is an ascetic artist. His attitude is conceptual: painting without seeing. His gesture is artisanal: fold and fold some more. This gives rise to images whose appearance he doesn’t control, which are beautiful almost in spite of him. He says that he never knows beforehand what will be produced.

Matisse and Pollock

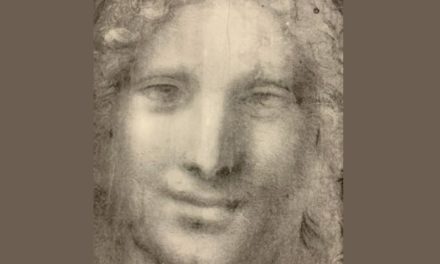

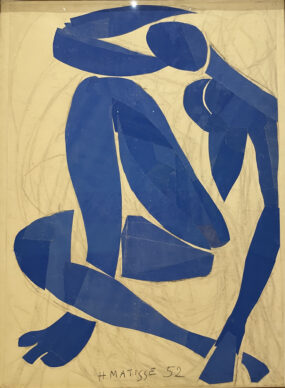

Here the true masterminds, the artists who pioneered this new art form, are the American artist Jackson Pollock and his modern predecessor, the French artist Henri Matisse.

130 works

The Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris is displaying 130 artworks, half of which have never been seen before and come directly from the artist’s atelier. There are two main points that make the exhibition interesting. The first is the principle of the series, which is particularly impressive in its visual power: the series of abstract works in iterations of various colours.

Experimentation

The second is the principle of experimentation. According to his different periods Simon would either fold, crumple or even knot… then he would move on to the second stage which consisted of painting what remained visible on the surface after his manipulations of the piece. “For him, painting is the disappearance and disfigurement of the image.

Anne Baldassari

He proclaimed it to be pictorial automatism,” explains the curator of the exhibition, Anne Baldassari. In 1982 Simon Hantai was 60 years old. He was celebrated, famous. France chose him to be the representative at the Venice Biennale. And yet it was after this event that the painter, who was always seeking the absolute, decided to withdraw from public life.

Pierre Hantai

He was disgusted by the artistic system, as revealed by his son Pierre Hantai, who describes his father fondly as a “petit paysan” (a small farmer or “hillbilly”).

Zsuzsa Hantai

But his widow, Zsuzsa, also describes how he carried on working right up until his last breath. The contemporary artist Daniel Buren, who met him in 1961, has written in depth in the exhibition catalogue about the methods and impact of his oeuvre. Simon Hantai is being brought back to life until 29 July in a masterful way to mark the occasion of the centenary of his birth.

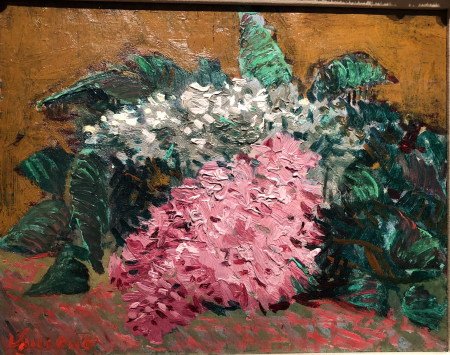

Panse

The Panses series (1964-1967) is a process that alludes to the cells present in all animate objects. It was, it would seem, inspired by a text by Henri Michaux in which he says: “Everything, truly everything, is to be taken up again from the beginning: from the cellules, of plants, of molluscs, of proto-animals: the alphabet of life”.

Meun

In 1966 Simon Hantai withdrew from the hustle and bustle of Paris to go and live on the edge of the forest in Fontainebleau, in the village of Meun. For a while he stopped painting and then he started the series, between 1967 and 1968, which would bear the name of the place where he was living. Here he used the knot method rather than the folding method. The Meuns are said to evoke Matisse’s cut-outs.

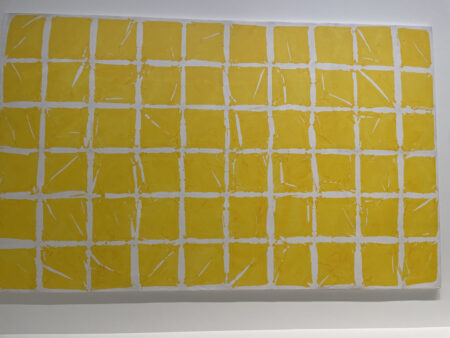

Tabula

Between 1972 and 1982 the painter created what he called Tabulas. Daniel Buren comments: The most interesting thing in my view in his method of working is his capacity to divide infinitely. The way he would rethink the large Tabulas, cut them up into pieces that are all identical and different, then cut them up again X times, so as to create variations of his paintings in different scales and forms.

Laissée

Zoologists refer to “laissées” (droppings) when they talk about the excretions of wild animals out in nature. Hantaï uses this ambiguous vocabulary to describe his last series from 1994-1995. These “leftovers” are produced from works that had already been made, from monumental Tabulas. He cut them up using a knife and then selected and reframed certain pieces.

Until 22 July 2022. Simon Hantaï, l’exposition du centenaire.

https://www.fondationlouisvuitton.fr/fr/evenements/simon-hantai-l-exposition-du-centenaire

Donating=Supporting

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.