The good Impressionnism

The word “Impressionism” may be ringing in the ears of the twenty-first-century man like a deterrent. Some people no longer want the endless greenish landscapes of late Pissarros,even though the artist was the great theorist of the movement, nor do they want more sickly-sweet, listless Renoirs from the end of the life of a man who nevertheless was once a genius of sensuality.

The Fondation Vuitton in Paris is presenting an exhibition of 110 artworks dedicated toLondon’s Courtauld collection with the subtitle “Le parti de l’Impressionnisme” ( A vision for Impressionnism).

Yet you must go and see this exhibition. For at least three reasons.

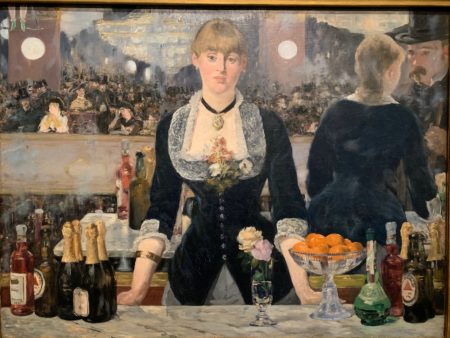

Manet

The first is about 1.3 metres wide and is called “Bar aux Folies-Bergère”. It’s Manet’s magnum opus and his last large canvas: a magisterial opening onto modernity.

Cézanne

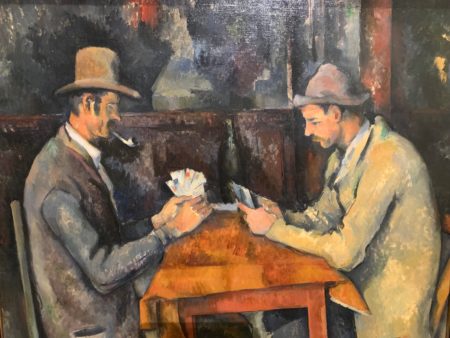

The second, “Les joueurs de cartes” (The Card Players) by Paul Cézanne haunts the viewer with its asymmetrical composition. Or how to create a masterpiece through imperfection. This is where the cubist Picasso comes from, and all that followed.

Lesson of collecting

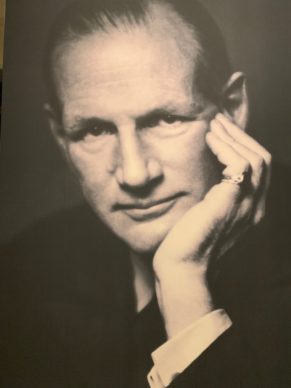

The third reason is that this is an extraordinary lesson in collecting, or how one man put together an ensemble of works in barely seven years which would go down in history and which tells the story of the beginnings of modernity itself – and not just impressionism – at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Between 1923 and 1929, the powerful British textile industrialist Samuel Courtauld managed to assemble a very consistent array of masterworks. This man in a hurry pushed forward with his monomaniacal enlightened quest, spanning the whole of Europe in pursuit of paintings, forty-odd years after their creation, produced by various giants of the field who resided in France, from Van Gogh to Cézanne, from Manet to Seurat.

Several times purchases from Paul Rosenberg in Paris can be noted.

No Picasso

Yet at the time Rosenberg also championed Picasso. But Courtauld didn’t go near the Spanish master. He was focused on something else. Courtauld’s determination and sheer speed of acquisition was no doubt related to his nature as a businessman.

He was assisted in this commando operation by a British dealer, Percy Moore Turner, who would incidentally enable him to meet another legendary collector known for his gargantuan pictorial appetites, Dr Barnes, whose masterpieces can still be seen today in Philadelphia.

In 1932 Courtauld created a foundation dedicated to the study of art history, the Courtauld Institute.

His godson Sir Christopher McLaren, positioned on the famous stairs of the Courtaulds’ old house, Home House, now transformed into a private members club, remembers his godfather.

When he died the foundation inherited practically his entire collection.

While today the Courtauld Gallery is getting a makeover in London at its premises in Somerset House, Paris is welcoming these paintings, which can be viewed as though in dialogue with the collections at the Musée d’Orsay.

Zoom on 5 paintings

Let’s zoom in on five paintings explained by Karen Serres, curator of paintings at the Courtauld Gallery.

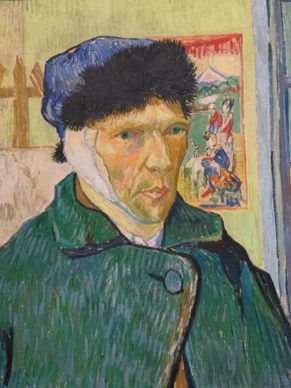

Vincent Van Gogh

Autoportrait à l’oreille bandée (Selfportrait with Bandaged Ear). 1889

On 23 December 1888, one bleak, freezing winter in Arles, the Dutch painter who was staying in the South of France, Vincent Van Gogh, deliberately cut off his own ear. He would paint 36 self-portraits in 4 years. This one, an iconic image of the artist martyr on the altar of society, would become famous.

Edouard Manet

Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère (A Bar at the Folies-Bergère). 1880

A few months before dying of syphilis, the great Edouard Manet made his definitive artwork.

Its heroine is a waitress at the famous new cabaret in Montmartre, the Folies-Bergère, where the women were known for being of easy virtue. Samuel Courtauld acquired it for a colossal sum (11,000 dollars, 22,600 pounds), over twice the amount he paid for the Van Gogh, the famous “Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear”.

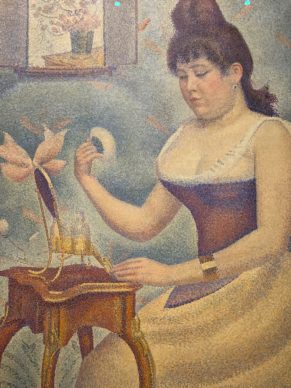

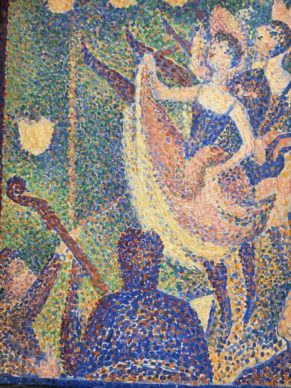

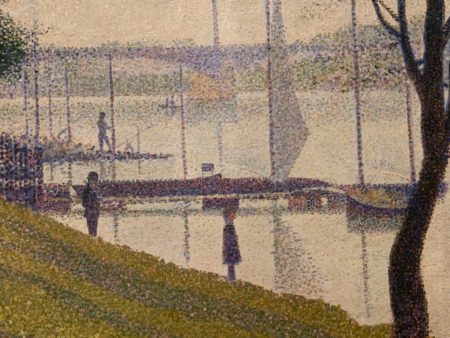

Georges Seurat

Jeune femme se poudrant (Young Woman Powdering Herself). Around 1888-1890.

Seurat (1859-1891) had a short life and this is the only portrait he ever produced in paint out of the 7 large-scale paintings that are known by him. It depicts his mistress Madeleine Knobloch, who gave him a son who died, like him, of diphtheria.

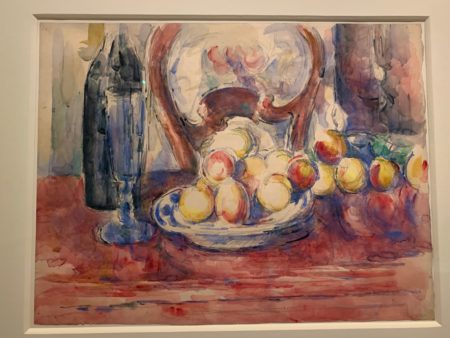

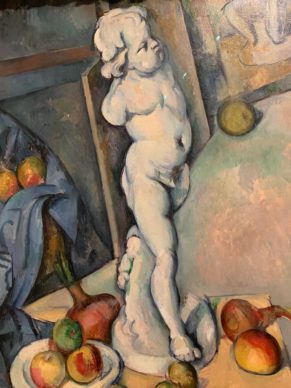

Paul Cézanne

Les joueurs de cartes (The Card Players). Around 1892-1896.

Paul Cézanne painted on the theme of the “card players” five times. One version belongs to the Metropolitan Museum in New York, another to the Musée d’Orsay, another one to the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia – Courtauld even went there to meet the American collector – and the last seems to have been sold for 250 million dollars a few years ago in Qatar.

Here it’s not so much the subject that’s important but rather the composition. The bottle isn’t there to indicate that they are drinking – there aren’t even any glasses – but it’s been positioned here to mark the middle of the canvas.

For the rest of the construction of the work is, as is often the case with Cézanne, conceived in imbalance: the table is twisted, the background cut into two unequal parts, one player’s chair is more visible than the other. This masterpiece is made from a communion of anomalies.

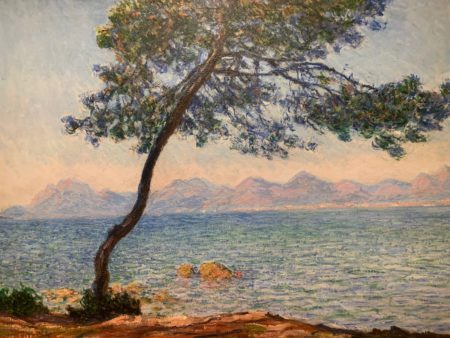

Claude Monet

Antibes. 1888.

This canvas was acquired by Elisabeth Courtauld, Samuel’s wife, from an English dealer. It reveals one of Monet’s important inspirations: Japanese prints. You can also see him returning to Corot’s compositions in Italy, where he would insert an almost incongruous element right in the middle of his painting. Here the pine tree is a character in its own right.

Until 17 June. www.fondationlouisvuitton.fr

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.