The programme features a large amount of expensive art, the most expensive of the last six months, being passed from one hand to another with creations dating from the end of the 19th century to the 21st. Although the catalogues have yet to been published, the most highly anticipated artwork is a famous piece by British artist David Hockney dating from 1972, “Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)”, with an estimate of 80 million dollars from Christie’s, which, if the sum is attained, is due to set a new record price in the category of works by a living artist.

This painting reveals a major trend, in market terms; that of auction houses increasingly pushing up prices before potential buyers have even been announced.

However, if there’s one thing that isn’t typical in the sale of this painting it’s the fact that the work is not guaranteed, or at any rate not at the time of writing.

In other words, the seller in question, the English billionaire Joe Lewis, is running the risk for now that the anticipated sum might not be attained at auction and that the work may even remain unsold.

Because these days the most high-profile paintings and sculptures presented at auction tend to be guaranteed, either by the auction house or more likely, and increasingly, by third parties.

Last May, out of the 65 contemporary art lots in the Christie’s evening sale (the high-end artworks) 32 were guaranteed and 7 lots out of the 40 in the impressionist and modern category. At Sotheby’s, 15 lots were guaranteed out of the 45 impressionist and modern lots presented and 18 contemporary works out of the 49 featured in the catalogue.

The principle of the guarantee is nothing new; rather, it’s the growing significance of the practice that gives it a unique power.

Among the investors there’s the auction house but also more importantly there are the funds specializing in art, the dealers, the banks and occasionally certain collectors.

To guarantee an artwork is to have the possibility, albeit with a risk of course, of obtaining a quick capital gain.

If I guarantee to buy an artwork for a total of 10 and it is sold for 20, the extra 10 will then be shared out, according to the stipulations of the contract, between the seller and the guarantor.

This is where it gets complicated. According to various sources in the business – who wish to remain anonymous – it would appear that auction houses these days place the guarantors in competition with one another to establish the guarantees.

So even before the auctions there’s a market of supply and demand that sets an initial value of the artwork.

The communications department at Christie’s refused to allow one of their specialists to comment on the subject, but they did send a statement saying:

“Christie’s believe that guarantees help to be able to offer the best selection of works to potential buyers. What is most important to bear in mind is that Christie’s has a stringent policy of full transparency when it comes to guarantees, and we take measures to ensure that all of our buyers are aware of their existence and understand how they work.”

Guarantees by a third party are indicated in the catalogue by a little sign (a dot or a circle) at Christie’s and likewise at Sotheby’s.

However, we do not know who the guarantor is, nor the total amount of the guarantee, nor the nature of the guarantee (how the gains are divided up), which may for example be lower than the estimated price.

What’s more, occasionally guarantees are passed on to other guarantors before the sale.

It can also happen that a work that hasn’t been guaranteed acquires a guarantee at the last minute, and that this significant arrangement is only announced in the auction room, out loud, at the moment when a lot is presented.

A market participant describes the ideal lot to guarantee: “It’s all about the great classics. It’s always the same artists which make money. Above 50 million dollars the guarantors become scarce. Today it’s really the hedge fund high-rollers who love to play around with guarantees.”

Grégoire Billault, director of contemporary art at Sotheby’s in New York, explains: “as the market for contemporary art has expanded considerably it’s been attracting more and more interest. The guarantee is considered as a new way of participating in the market. Primarily, it offers the seller the confidence to pass on their goods without any risk, in exchange for a share in the percentage of the success. People are bound to see this as a financialization of the system, but it primarily enables major works to be put on the market.”

Brett Gorvy, co-owner of the Levy-Gorvy gallery in New York and London and former international head of modern art at Christie’s, observes: “The best situation consists of finding someone who is truly interested in the painting. If they don’t obtain it, their disappointment will then be compensated for by the money they’ve gained.”

The Fine Art Group in London is a company that specializes in art investment.

Their founder and president Philip Hoffman states that they manage two funds dedicated entirely to guarantees, an area they’ve been investing in for the past five years.

“We estimate that over 40% of third-party guarantors are now buying the works. Certainly guarantees can be a good mechanism for collectors or dealers who are happy to buy works at a level with which they are comfortable whilst at the same time benefitting from any upside should the bidding go past their mark. The Fine Art Group has been very involved in this area of the market over the last 5 years, and thanks to our track record of successfully pricing at auction, we also now advise our private clients and conduct risk due diligence, on their behalf, before placing guarantees.”

In recent months a number of record prices have had guarantees.

This was the case firstly for Leonardo da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi” sold in November 2017 for 450 million dollars by Christie’s. According to industry sources the extremely restored painting – the Louvre Abu Dhabi has still not yet resolved to exhibit it – may have been guaranteed for a total of 100 million dollars, possibly by Taiwanese billionaire Pierre Chen.

Similarly, the record price of 110.5 million dollars for a work by Jean-Michel Basquiat in May 2017 at Sotheby’s was guaranteed. As for the largest painting ever made by the Franco-Chinese painter Zao Wou-Ki, which sold for 65 million dollars in September 2018 at Sotheby’s in Hong Kong, it would appear it also had a guarantee.

A dealer concludes: “The problem is that the prices, before they even reach the auctions, are already established on an artificial base put in place by Sotheby’s and Christie’s. Then, propelled into the higher tiers, they go on to serve as a reference for the art market.”

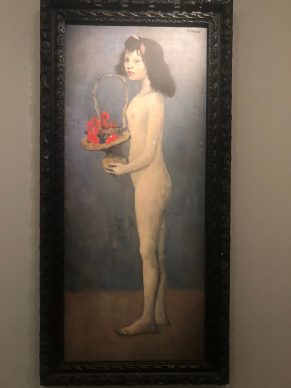

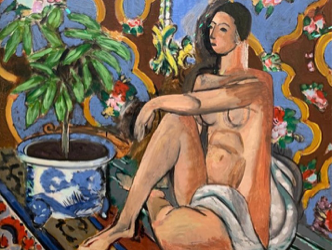

All the works reproduced in this post were guaranteed.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.