Klimt or Klint?

There are two kinds of modern art enthusiasts. Those who, upon hearing the name Hilma af Klint (1862-1944), assume it to be a typo for a relative of Gustav Klimt, the famous Austrian painter. And the others, fewer in number, who had the privilege of visiting the revelatory 2018 exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York which was the first major international retrospective of the Swedish artist.

Quietly doing abstraction

There indeed lived a woman from a prominent Stockholm family who quietly practiced abstraction, as early as 1907, on a very large scale and without wedding her gestures to any particular theory. For she confessed in her writings to have been guided and inspired by visions.

It would be a few more years before Kandinsky, Mondrian, Delaunay, Kupka and Picabia (See here the last report about Picabia) would introduce the desire to no longer represent the material world into the zeitgeist.

Hypnotic work

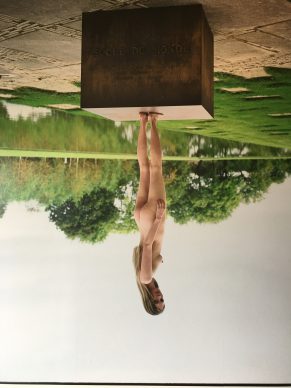

In the 21st century, the revelation of Hilma af Klint has reverberated far beyond a small circle of art historians, for her work is hypnotic. Some of her pieces more closely resemble the ethereal art of the psychedelic 1970s than the product of early modernism.

While a monographic exhibition is planed in Paris for 2026, the prodigious Swedish artist is currently the subject of a highly successful show at the Guggenheim Bilbao, running until Feb. 2 (See here a report about an other exhibition at the Guggenheim Bilbao).

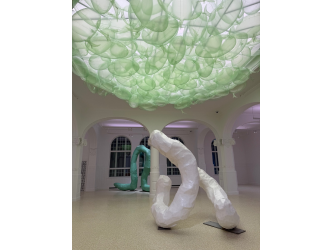

Klint+ Gehry

The pairing of Klint and Gehry (Frank Gehry being the museum’s architect; see here an interview of Frank Gehry) performs exceptionally well. One very high-ceilinged room, dedicated to her large-format paintings over three meters tall, transforms the space into a veritable cathedral.

To appreciate is to support.

To support is to donate.

Support JB Reports by becoming a sustaining Patron with a recurring or a spontaneous donation.

Heavenly beauty

A mystic and a practitioner of spiritualism, Klint belonged to the Theosophical Society, an organization that believes all religions hold a fragment of truth. She created these immense compositions, titled The Ten Largest, in the aftermath of a revelation. Her objective: to depict “a heavenly beauty.”

Daniel Birnbaum

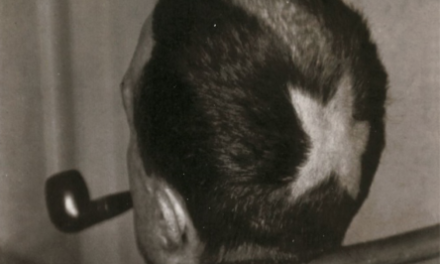

Whether in pastel or high-contrast backgrounds, sinuous shapes, flowers or diagrams—as Daniel Birnbaum, author of the artist’s catalogue raisonné, explains: “She was very prolific. In ten years, she produced 193 paintings she called Paintings for the Temple.” (See here a report about Daniel Birnbaum)

Parallel life

In a parallel, more conventional life, she sold her figurative work. With time, her visual language evolved, and her compositions took on a retro-futuristic look, blending chivalric figures and deities with geometric forms.

20 years after her death

Conscious of the impossibility of being understood in her own time, she decreed that her work be kept aside for 20 years after her death. It wasn’t until the 1980s that Sweden finally opened its eyes to the treasure of Hilma. She is now the object of a global cult following which will surely continue growing.

Until February 2

www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.