Travel hopefully

“To travel hopefully is a better thing than to arrive.” This famous phrase from Scottish writer Robert Louis Stevenson can be perfectly applied to the new large-scale exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, on show until 10 August and dedicated to another British citizen who lives between Switzerland and Spain, the “starchitect” – as they say these days – Norman Foster (born in 1935).

Sol Lewitt, Norman Foster

The process

Foster takes us through the process of creating his projects. For the first time, the largest gallery in the French national museum of modern art, across nearly 2200m2, is entirely dedicated to one of these architects. Here, more than merely attempting to admire the achievements of the man who’s shaped numerous sites around the world, from the Bank of China in Hong Kong to the Apple headquarters in Cupertino, California, we are first and foremost diving into his mind and encountering his myriad references.

60 years of activity

Norman Foster

The show celebrates the 60 years of activity of the Norman Foster design practice, with its 1800 employees around the world. For him, drawing is an obsession. The curator of the exhibition, Frédéric Migayrou, even explains that the architect sketches every moment of the day, even when he’s out at a restaurant.

Immersive showcase of drawings

The exhibition opens with an immersive showcase of drawings, comprising countless projects on paper but also no less than 300 notebooks (out of 2000 in existence) containing spontaneous sketches, as well as a cabinet featuring 250 photographs in postcard format, reminiscent of German painter Gerhard Richter’s Atlas, showing his iconographic references: architectural details, facades, Japanese shoes or the interior of a plane.

Im childlike

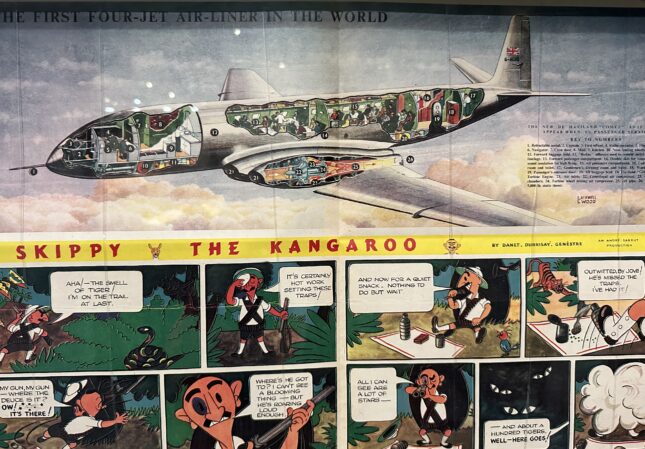

After this “decompression chamber”, we enter deep into Foster’s mind. The first key stage is the evocation of his childhood universe, growing up in Manchester in a modest family with youth magazines that he read avidly. “The cartoons from the time of my adolescence had a great influence on me, because they brought future technologies to life. You could see the engine of a plane, a locomotive, an automobile. Here the future was always presented as better and more exciting. I still think like that. Because the figures show us that humans are living longer, in better health. Statistically – contrary to what people read in the newspapers – living standards are better compared to the past and we’re benefiting from longer periods of peace and prosperity. In this respect I think I am still very childlike. I have kept my passions and my obsessions.”

Antique automobiles

Brancusi & Le Corbusier’s Avion Voisin Car

The man who was once the young boy from Manchester has a great passion for antique automobiles. During the summer of 2022 he curated an exhibition at the Guggenheim Bilbao on movement in art, architecture and the automobile, which attracted 750,000 visitors, a record for the institution. Here he is only showing two automobiles, including the one that belonged to his illustrious predecessor Le Corbusier during the 1920s, from his personal collection.

Sculpted car prototypes

Richard Buckminster Fuller

“The prototypes for cars, even in the digital era, are still literally sculpted in earth, life size. The process is remarkably similar to that of Renaissance sculpture workshops.” Fittingly, the vehicles are placed alongside two works by one of the most eminent sculptors of the 20th century, Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957).

Brancusi

Ai Weiwei

“When Brancusi went with his artist friends to visit an aviation display he declared: It’s the end of sculpture. But for him it was the start of a new phase. In the exhibition we are presenting his highly geometric ‘Endless Column’ and his particularly tapered ‘Bird’ alongside a DC-3 propeller, a present from my wife. “I am fascinated by the common denominator between design and what are known as the fine arts, and these links with craft too. I would like the barriers between these different categories to disappear.”

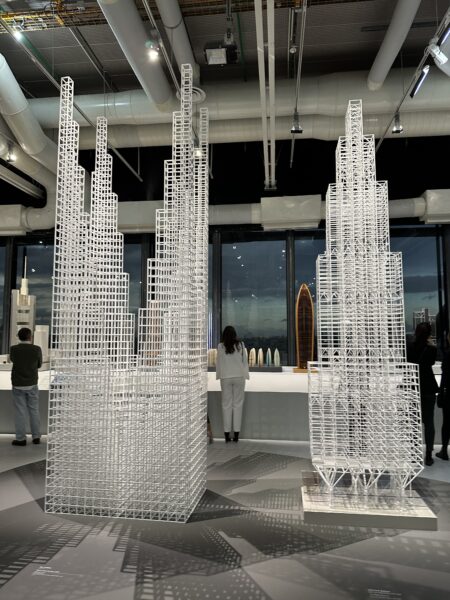

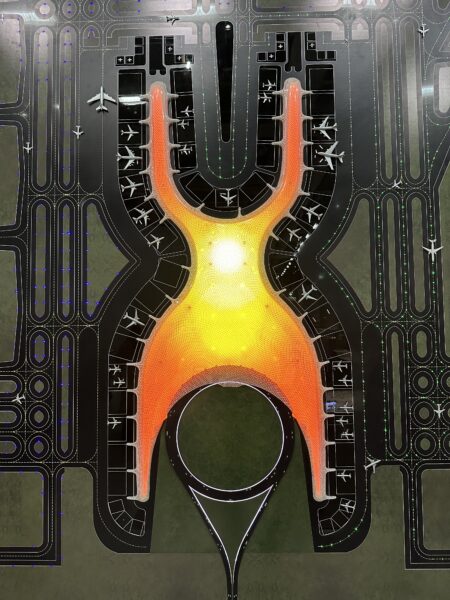

Models like works of art

The exhibition gives pride of place to the models for his architectural projects, which constitute works of art in themselves. See for example the one for the Amman airport in Jordan (2005-2013), whose central, illuminated body seems to assume the form of a four-legged animal. See also the diorama (the images invented in the 19th century, in three dimensions, which allow us to see in depth) of the Climatroffice, an extraordinary building project – shaped like a saucer and never realized. As early as 1971 Foster was preoccupied by questions of harmony with nature in this edifice conceived in collaboration with the legendary American futurist architect, Richard Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983).

Sculpture or architecture?

Norman Foster

Curiously, while the Centre Pompidou rolls out the red carpet, there are no major buildings in Paris marked with the Foster design signature. In France more generally however, he designed the Millau Viaduct (1994-2004), among other things, which stretches across 2.5km (and is slightly curved to give users a better sense of perspective) and the pavilion at Marseille’s Vieux Port (2010-2013), a sheet of reflective steel measuring 46×22 metres positioned on eight slim columns, which has become one of the city’s attractions. It is closer to sculpture than to architecture, strictly speaking.

Each time an exploration

Norman Foster

But one should not seek out a single style in Foster’s work. His desire, his pursuit of beauty, operate as he himself says by way of conclusion: “through the wish to highlight the view, the sunlight, contact with nature… It doesn’t really depend on the materiality of the building. That’s why the materials used for the projects presented can vary from wood to marble to stone or concrete. Each time it’s an exploration.”

Norman Foster. Until 7 August. Centre Pompidou. www.centrepompidou.fr/fr/

Also:

Taschen : Norman Foster, by Philip Jodidio. 1064 pages. € 350. 9,7 kg!

Norman Foster

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.