Great painter

It’s generally taken as a given that Gerhard Richter is one of the great painters from the latter half of the 20th century. But for anyone who may still have doubts on the subject, it’s worth paying a visit to the Kunsthaus Zurich before 25 July. The institution is devoting a large-scale exhibition to Richter with a focus on his landscapes; one of the subjects he returns to obsessively along with his portraits.

Infinite variations

Here we discover the infinite variations the artist applies to his idea of the landscape. 140 artworks, including 80 paintings, map the landscape of Richter’s landscapes across all the mediums he’s used from 1957 up until 2018.

Photos of landscapes

Richter is not a landscape painter in the sense that the term was used during the times of the Impressionists. Clearly there are no works here that have been made “sur le motif” (“on the ground”) as they used to say, but instead there are paintings of photos of landscapes, which may have been taken by the artist, but not necessarily.

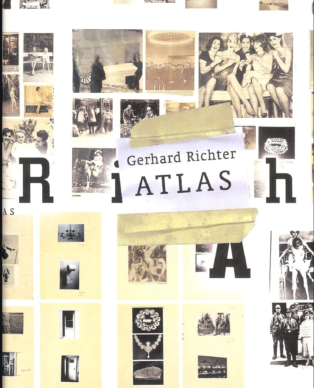

Atlas

The German artist has been building a kind of iconographic database since 1962 called Atlas, which can be accessed on his personal website and in book form. It is a collection of photos, newspaper articles, sketches, but also paintings. The ensemble serves not only as a catalogue raisonné up until 2013 but also as a source of raw material for his work. For as we can see in the exhibition, Richter also produces photos of his paintings of landscapes… So these are photos of paintings based on photos…

Abstraction and figuration

Nothing is simple in the world of Richter. It’s useless to try to pigeonhole him one way or another. He also juggles abstraction and figuration. And as I noted at the remarkable little exhibition at the Guggenheim Bilbao in 2019 featuring 10 of his seascapes (See the report here) – figurative paintings which are immediately identifiable as such – they nonetheless resemble completely abstract pieces once you get up close.

Gestural paintings

There are also photos covered with daubs of paint, which are very gestural. Plus there are the figurative paintings in which he removes the main motif…

September

In this respect I am thinking for example of “September”, a small canvas painted in 2005 depicting the attack on the twin towers, which belongs to Moma in New York. It has not travelled to Zurich, despite the fact that it could well have featured as part of the exhibition since the artist literally erased the moment at which the plane crashes into the tower.

Catherine Hug

Let’s proceed through Richter’s labyrinthine non-categories. As the curator of the Zurich exhibition, Catherine Hug, explains very well, he can take as inspiration photos with quasi-topographical properties which his paintbrush will pervert to give them a more uncertain appearance. “The black and white paintings are like portraits of cities. They are seen from above as though from a plane.”

Through the war

Given the fact that Richter is seen – rightly – as a German artist who lived through the Second World War, having been born in the city of Dresden which would go on to be largely destroyed, these black and white cityscapes are instinctively associated with ruins. “But the Atlas proves that these are not ruins,” explains Catherine Hug.

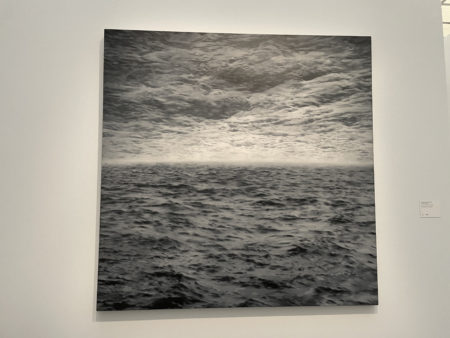

Gustave Le Gray, Friedrich

Is Richter playing with the viewer? Perhaps. In any case it encourages us to question the subjectivity of the image. He is well-versed in art history, as we can see through references which are made explicit to varying degrees: like the great French photographer Gustave Le Gray in the 19th century he creates special effects by sticking a photo of the sea and a photo of the sky together to create a fictional landscape. The romanticism of Gaspard David Friedrich hovers over several of his canvases in which a male figure is no longer alone, confronted with nature.

Georges Seurat

But the Venice scene from 1985 depicting a young woman (apparently Isa Genzken his then wife) on the waterfront also strangely resembles a preparatory study by the post-impressionist Seurat for his wonderful painting “Un dimanche après-midi à l’Ile de la Grande Jatte”.

Subliminal St Gallen

Lastly, as part of the artist’s great juggling act of switching constantly between figuration and abstraction over many years, there are also his pure abstractions to which he gives place names. In 1989 the University of St. Gallen commissioned a painting from him which he named after the town. Usually placed next to a window through which you can see the whole town, the 3.40 metre long canvas is made up of drips and colourful ridging effects. It presents a subliminal vision of St. Gallen.

Metal ball

We also notice that the exhibition features, as is often the case, a metal ball that seems to be saying to the viewer: you are the landscape. Or perhaps: you are the one who creates the landscape.

Conceptual art

For me, Gerhard Richter is a conceptual artist who uses – among other things – paint. Like the American artist Sol LeWitt with his wall drawings towards the end of his life (although Richter is the artisan of his own artworks), he explores all possibilities while still adhering to the principles he has maintained since his beginnings: navigating different kinds of images and their limits.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.