War

War. Economists and politicians alike are readily comparing the impact of the coronavirus to that of a military conflict. The 20th century’s most devastating and traumatising conflict was the Second World War.

Disgust

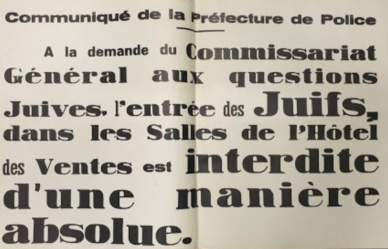

But back then, as the specialist historian Laurence Bertrand Dorléac writes, “the heart contracts with disgust” when we examine the fact that in France “the art market prospered from an economy destabilized by Nazi and Vichyist laws,” with “the behaviour of scavengers, pleasure-seekers and freeloaders”. This trade was fuelled by a huge mass of artworks plundered from Jewish collectors and dealers, which continue to crop up from time to time on the art market today.

Picasso/ Gagosian

One example of this is a pastel work by Picasso entitled “Head of a Woman” from 1903, a typical Blue Period piece, which was recently returned to the heirs of a German Jewish banker who had been persecuted by the Nazis, Paul Von Mendelssohn-Bartholdy. The work had previously been the property of Washington’s National Gallery, and according to the Wall Street Journal it is Gagosian gallery who have now been tasked with selling it for a price that could be in the region of 10 million dollars.

Koninck/ Christie’s

On 1st April 2020 Christie’s also declared in New York that they had contributed to the restitution of a picture painted in 1639 by Solomon Koninck, who specialized in genre scenes in Amsterdam. The canvas, which was part of the Adolphe Schloss collection in Paris, had been confiscated by the Nazis in 1943, sold by a dealer who was close to Hermann Göring, and put up for sale at Christie’s in 2017 by a Chilean art lover before the FBI were alerted…

Massive trade

It should be said that between 1940 and 1944 there was a massive and highly structured art trade taking place in the city which was the global epicentre for art at the time: Paris. According to Laurence Bertrand Dorléac “in a single year, 1941-1942, 2 million objects passed through the Hôtel Drouot (…) a cynical theatre of prosperity.” To put that in perspective, according to the president of Drouot in 2020 Alexandre Giquello, 500,000 lots are currently sold annually at auction on the same premises.

The art market under the Occupation

In 2019 the historian Emmanuelle Polack published “The Art Market Under the Occupation” (Le marché de l’art sous l’occupation) (2), which shone a spotlight on the current state of this delicate issue. Since then she’s even been enlisted by those in charge of research at the Louvre to investigate the origins of acquisitions made by the institution between 1933 and 1945. According to her, it is undeniable that during wartime “amid the context of inflation, art was elevated to the rank of a safe haven”.

Benefit from the black market

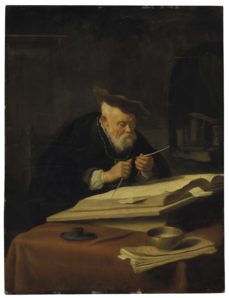

The sociologist Raymonde Moulin has already pointed out (3) that those who profited from the black market (they were described in France by the acronym BOF, which stands for ‘boeuf, oeuf, fromage’ or beef, egg and cheese, in reference to the foods sold for higher prices during wartime on the black market) invested in decorative painting. Each period has its own art market trends, and the most important in those troubled times were those dictated by the Germans, as Emmanuelle Polack explains. “It’s no surprise that the new clientele at the Hôtel Drouot favoured German, Dutch and Flemish paintings and drawings from the 15th, 16th and 18th centuries, like Durer, Cranach, Rembrandt, Rubens, Van Dyck… The fact that tastes were dictated by an ideology also quite quickly produced an artificial inflation in the value of these styles, distorting market prices.”

Metamorphosized tastes

Corinne Hershkovitch is a lawyer who has specialized in art restitution for 25 years in Paris. She is a keen observer of transactions from this period and has recovered looted artworks on behalf of the heirs of their legitimate owners in a large number of global institutions, from the Chicago Art Institute to the Louvre. “Tastes at Drouot metamorphosized with the war. From October 1940 Jews, whether they were dealers or collectors, were prohibited. Around the same time, the Germans devalued the franc, giving them enormous buying power to make acquisitions in France. Hitler sent his emissary-dealers to set up his museum in Lintz and the dignitaries of the regime rushed to acquire art in Paris. But paintings were also a safe haven for the Jews who were being persecuted. The Parisian dealer René Gimpel, for example, was well aware that money wasn’t worth anything anymore. According to him, the smaller landscape paintings were typically easy to sell on.”

Record price for Cézanne

Impressionist art in the broad sense, from Cézanne to Pissarro, was also of major value at the time. On 11 December 1942 part of a collection was put up for auction belonging to a recently deceased dentist, known throughout Paris as a great lover of the field, George Viau. It contained a painting by Paul Cézanne, “La vallée de l’arc et la montagne Saint Victoire”, which obtained the highest price of the period: 5 million francs. The war led to a boom in prices; an observation confirmed by Emmanuelle Polack, who notes that on the occasion of the sale, still in 1942, of Jacques Canonne’s collection, which included pieces by Matisse, Dufy, Bonnard and Monet, the prices multiplied overall by nine. The painter André Derain was one of the lucky ones whose canvases were subject to high demand. One explanation for this, among others, might have been that he took part in the famous “cultural” voyage of 1941 which featured heavily in propaganda in Nazi Germany.

Looted goods in Nice

In Nice, part of what was known as the “free zone”, the auctioneer Jean-Joseph Terris was also particularly active, with artworks readily put up for sale by exiled Jewish collectors but also by the Commissariat for Jewish Affairs, who liquidated the looted goods. This was the case for the Dorville collection, which contained 450 lots, including a large number of drawings by an artist who back then was considered to be a safe investment and was therefore expensive, but who has been completely forgotten today, Constantin Guys (1805-1892). The draughtsman was appreciated for his scenes of daily life throughout Paris. Some of his works sold for over 50,000 francs each at the time.

Money for degenerate art

Lastly, the Germans were perfectly aware that the art they described as degenerate had commercial value. They therefore didn’t hesitate to sell, whether discreetly or at Drouot, the avant-garde works of Picasso, Matisse and Braque, which they abhorred and were officially meant to be destroyed. “The prices oscillated between 30,000 and 100,000 francs,” far below the great heights attained by Cézanne, Degas, Renoir and Sisley, observes Mickael Szanto (4).

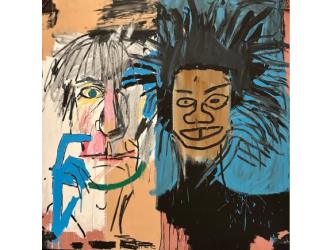

Auctions in Lucerne

But most importantly, as Pati Hertling, a former legal expert based in New York who specialized in art restitution, points out, “it was in Lucerne where you could find the operating base for the trade of this ‘Entartete Kunst’ [Degenerate Art] which was displayed and ridiculed in Germany in 1938”. Under the hammer of a certain Theodor Fischer, the Nazis put up for sale, for relatively low prices, the avant-garde works of these “Judeo-Bolsheviks”. “We hope at least to make money from this garbage,” wrote Goebbels (5). And so in 1939 125 of these paintings from German museums were put up for auction. The star lot was a self-portrait by Van Gogh estimated at 250,000 Swiss francs, which would be bought by an American for 170,000 Swiss francs. Today it belongs to the museum at Harvard University. In total, the artworks made 500,000 Swiss francs (around 115,000 dollars) with prices lower than those recorded in Paris or New York over the same period.

Safe haven and bargain

Although today’s circumstances are not comparable to those of the early 1940s, we do see several common aspects. The first consists of seeing art as a safe haven. The second is the fact that there are a number of people in possession of liquid assets, including those who ordinarily would be uninterested in painting or sculpture, who are currently looking for an art “bargain”.

From this perspective, it is worth being cautious. The crisis is not re-establishing justice within the values of art. It is simply establishing other, often more conventional, criteria. Who will be the Constantin Guys of today, highly esteemed for a few years before falling into art-market obscurity?

A lot of fakes

Moreover, the rush and discretion that often accompany what are presumed to be “bargains” can lead to irreparable errors. A number of paintings sold at Drouot during the war were often wrongly attributed or even fakes. This held true for old masters as well as modern art. The best example of this was the Cézanne landscape sold in 1942 for the record price of the occupation period of 5 million francs. It turned out to be a fake!

(1) L’art de la défaite 1940-1941. Editions du Seuil. 2010.

(2) Le marché de l’art sous l’occupation. 1940-1944. Editions Tallandier. 21,50 euros.

(3) « Le marché de la peinture en France ». 1967

(4) L’art en guerre. Catalogue of the exhibition at the Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris. 2012-2013.

(5) Stephanie Barron “Degenerate Art. The Fate of the Avant-garde in Nazi Germany”. 1991. Catalogue of the exhibition at Lacma.

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.