Like good old days

At the Louvre you’d think we were back in the good old days before Covid: mass tourism has resurfaced with its crowds and queues under the Pyramid, but we’ve also seen the return of an extremely ambitious programme. The new exhibition, baptized with the anodyne title “Les Choses” (“Things”), is – despite appearances – a show of force from the institution: its contents are breathtaking.

Edouard Manet

Knocked out by masterpieces

The art historian , Laurence Bertrand-Dorléac (there is no video interview. She does not like speaking English) has overseen an exploration across all eras mixed together of the idea of the still life. “In our noisy world, artists invite us to pay attention to the things that are quiet and small,” she says. We leave feeling knocked out by this series of masterpieces, with the exception of the contemporary art pieces, which is a weaker selection.

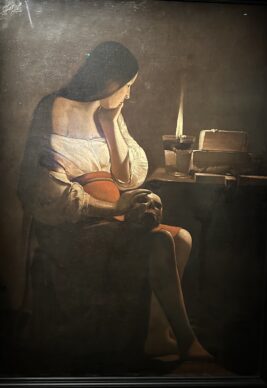

Georges de la Tour

170 works

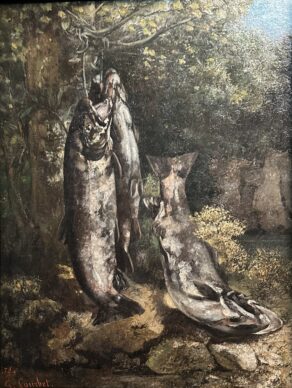

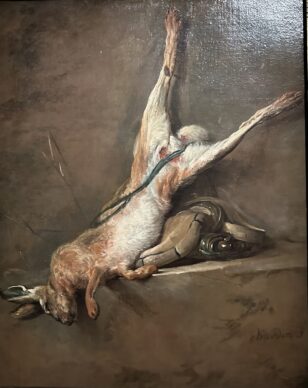

Out of the 170 paintings and sculptures on display, taken from 70 museums, two sections are particularly fascinating, located in the middle of the exhibition layout. “La bête humaine” (The Human Animal) addresses above all the use of the image of dead animals by painters to portray suffering. An impactful and powerful visual, starting with a hare with its head lowered and paws outstretched resembling a woman’s legs, painted around 1739 by the genius of the still life, Jean-Siméon Chardin. One of the authors of the Encyclopaedia, Denis Diderot, said of him, with regards to his remarkable still lifes which are present in various versions in this exhibition, that he admired his method of illuminating objects from within.

Gustave Courbet

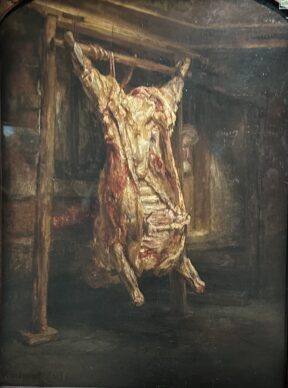

Rembrandt

Rembrandt

Nearly 80 years earlier, Rembrandt depicts the height of everyday savagery, the raw truth: an ox at the slaughter, entrails all on show, with grandiose light effects on the reddish flesh. Behind it, a servant watchfully peeks her head round the corner to lend some lightness to the scene. Visual virtuosity: Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1828) sculpted “La grive morte” (“The Dead Thrush”) out of marble in a small bas-relief which literally comes out of the painting. The bird hangs, in relief, as though fossilized. It is artfully placed alongside a canvas, “Nature morte aux trois oiseaux morts” (“Still Life with Three Dead Birds”), a polychrome version along the same theme by the specialist in hunting still lifes: Jean Baptise Oudry (1685-1755). The curator has amused herself with these parallels at various points in the exhibition.

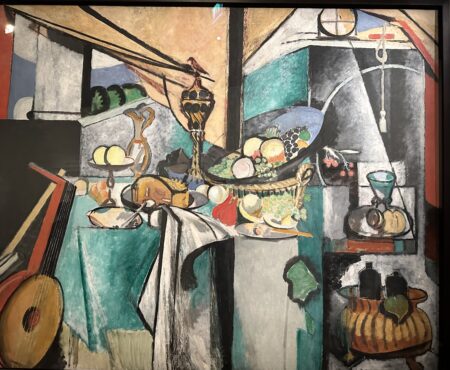

Matisse/ Heem

Jan Davidsz de Heem

The most grandiose among them, a bridge linking art history, involves placing a large still life by Matisse, painted in 1915, next to another by the Flemish artist Jan Davidsz de Heem (1606-1684) which served as its model. The original version in chiaroscuro is in this instance hanging right beside the cubist one, which works the shadows with the help of large black lines in contrast with the emerald green.

Henri Matisse

Goya and Géricault

Jean-Simeon Chardin

Goya, around 1808, focused on the detail of a sheep’s head, depicted with its murky eye alongside a segment of the animal’s body. To give some context: the Napoleonic wars in Spain… Painters like to depict humans as animals, especially when talking about politics… Around the same time, Géricault took it to the final stage. He stole a man’s arm and foot from a morgue. You could say that this still life, a “nature morte” which truly was dead, could have been a training sequence ahead of his bravura piece, the “Radeau de la méduse” (“The Raft of the Medusa”).

Francisco de Goya

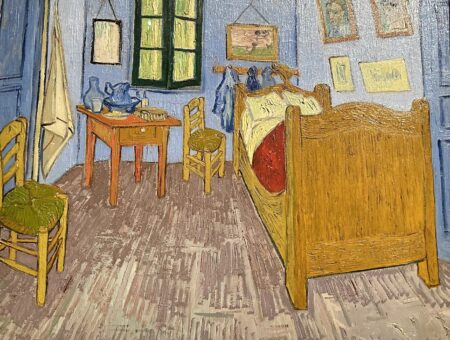

Van Gogh bedroom

Vincent Van Gogh

Laurence Bertrand-Dorléac has an expansive vision of the still life. In the next room, to express the question of the solitude of the artist surrounding himself with objects, there is a calm and poignant icon painted by Van Gogh in 1889: his bedroom in Arles. It was an obsession: he painted it three times over the course of a few months, to depict the little boy’s bed, the paintings on the wall, the longed-for simplicity. The surrealist part of the exhibition corresponds to what was probably the golden age of representation in “Les Choses”. Dali is breathtaking with his large-scale painting, “Living Still Life”, from 1956 which blends together a sea view, a laid table, geometric shapes, and sexuality in a hyperrealist style.

Salvador Dali

And Duchamp

Gerhard Richter

Lastly the real theoretical surprise of this exhibition lies in the categorization as “still life” of the famous and now iconic “Porte-bouteilles” by Marcel Duchamp. Or in other words, how one of the first objects to be turned into a work of art under the denomination of “readymade”, through the magic of the artist’s decision, ratified a new society: that of the industrial age where consumerism reigns. This was only in 1914. The best artists are seers.

Until 23 January. Les choses, une histoire de la nature morte. www.louvre.fr/

Support independent news on art.

Your contribution : Make a monthly commitment to support JB Reports or a one off contribution as and when you feel like it. Choose the option that suits you best.

Need to cancel a recurring donation? Please go here.

The donation is considered to be a subscription for a fee set by the donor and for a duration also set by the donor.